I met with Michal Rovner at Pace Gallery to see the opening on January 30, 2019, of “Evolution” which is the gallery’s first exhibition of Rovner’s work in Geneva. The show coincides with the opening of Rovner’s “Dislocation” show at Espace Muraille, also in Geneva, which we went to together afterwards. Rovner was born in 1957 in Israel, and had a solo show of her video work at the Whitney Museum of America Art in 2002. She then represented Israel at the Venice Biennale in 2003. She has been represented by Pace Gallery since 2003. Rovner is currently working on installations for the public realm at the new Canary Wharf Crossrail station in London.

Rovner is perhaps best known for her non-narrative, timeless video installations, focusing on the movement of people and issues of identity, and what it means to be human. She videos people from different places, such as Russia, Romania, and Israel, and then erases the details until they are just representational images of humans, and could be from anywhere. She has experimented with how little information needs to be given in order to recognise that a mark is human. To connect her technologically-advanced work to the past, to archeology and the landscape, she also has made projections onto ancient stones. Her work is relatable and mesmerising as rows of people move across the screen, sometimes glowing like the embers of a fire, sometimes reflected in the eyes of a jackal. Her work becomes even more layered with meaning when Rovner explains the ideas behind the images.

Michal Rovner:

I have two exhibitions in Geneva at the moment and both exhibitions are very different, they are two sides of the moon, but both are relating to something that is going on in the world and relating to humanity. “Evolution” is looking at text and the way it reflects the state of us, that we are what we write, and the text is what represents us. Of course text started on stones, in Mesopotamia, and with hieroglyphs and this was the beginning of history and this was marks on stone. I relate to this concept as an artist, to leave a mark, and to leave a permanent mark. And to make sure that it will be secured, and it will be safe.

And I lived with this concept, growing up in Israel where you are exposed to different layers of time, wherever you go you see layers of time, and stone, and the facts and truth are engraved in stone. Now we are in a different world, and the new text has taken over in the last few years. It is not even handwriting, it is not a typewriter but it is the binary text, black and white, counting, calculating, numbers, etc. And we are becoming part of a very big system of bar codes, artificial intelligence, and the wish to clone things, duplicating, and duplication. If you think about computers, what they do is add and subtract, but the thoughts of humans are much more abstract and open-ended.

74-13/16” × 42-1/2” × 5-3/8” (190 × 108 × 13.7 cm) Edition 1 of 5 + 2 APs

No. 69383.01 @ Michal Rovner, Courtesy of Pace Gallery. Photo credit: Annik Wetter

We start with this work which is on stone and I always work with footage of real people and I filmed 50 people at the age of 50 in Russia, Romania, and in Israel, and I asked them to hold hands. It is like a row or chain across the topography. I am not so interested in what it means but in how it looks and I love the appearance of it. I always film real people but then I erase the details so they could be anybody, anywhere, and I am always looking for something underneath the story. So there is never a narrative.

Kristen Knupp: Is this a kind of a history of humanity?

MR: Maybe, and maybe it is a desire of humanity to write its own story. And there are the erasures of time. I don’t project the people across all of the stone because there is the erasure of time, and of the story, maybe reflecting ignorance, and lost facts.

KK: Is this a positive interpretation of humanity?

MR: I never answer about positive or negative, for me it is indecipherable. It is an unresolved text about humanity, for me it is not resolved. It is both good and bad, humanity is not always so great, there are some things that have to be watched out for.

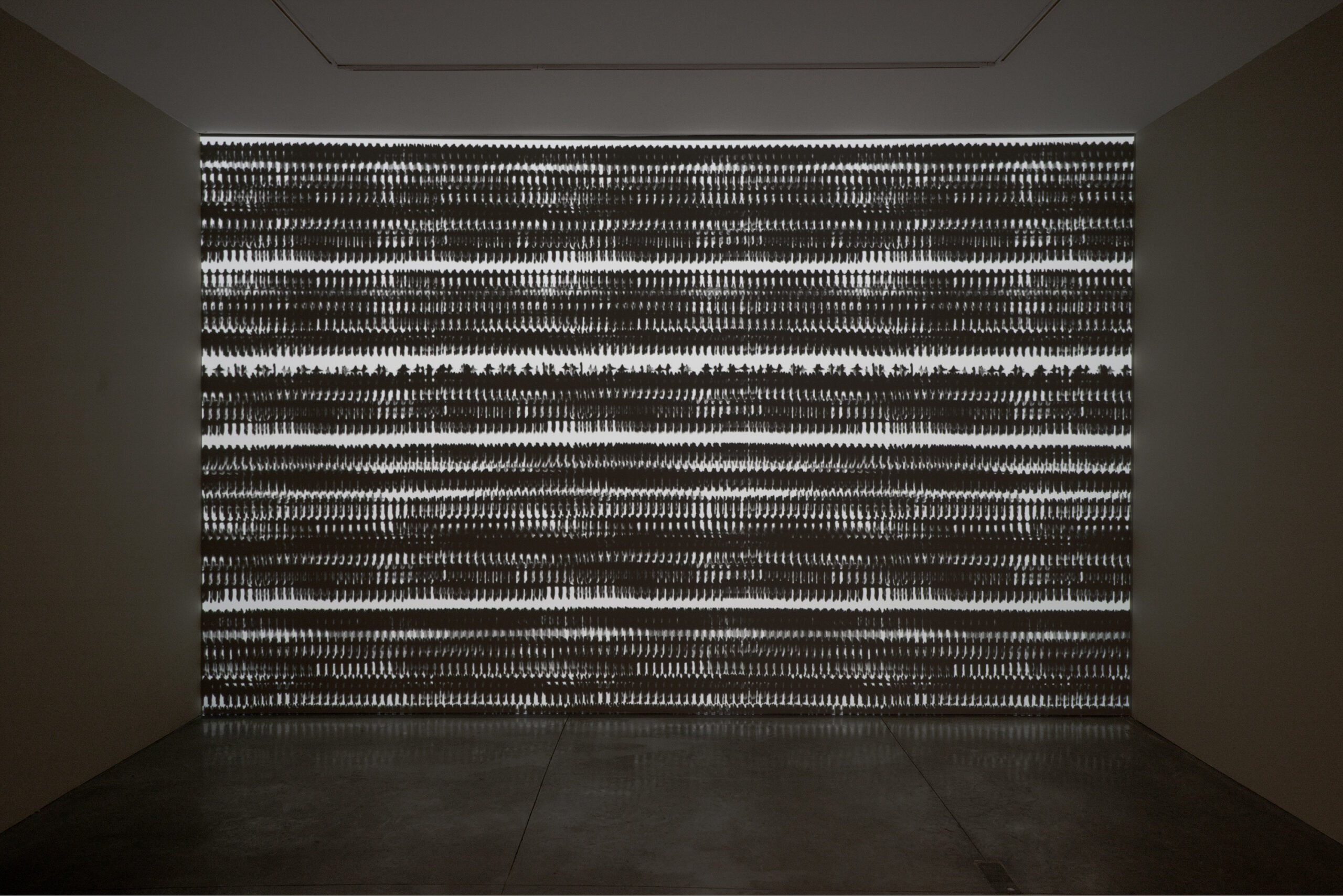

You see this piece is black and white, it is like genetics, the people are duplicating and changing from two to one and one becomes two, so they are changing places. So this piece makes a pattern. This is based on a human figure, in fact it is my figure. I am not interested in self-portraits, but I use my figure to represent humans. We are part of very big systems, and we don’t always know where it is going. It could be good or it could be bad also.

KK: What about technology, we’ve been part of a cog in a machine for a long time, since the Industrial Revolution or even before that, has it changed since then?

MR: I think there was a feeling that industry would change the world for the better. I did an installation in the Ruhr Valley in Germany, and the architecture was so big and strange looking, and this was the new hope of humanity at the time, the machinery and industry. And one of the first things that happened was these machines started to make the arms for World War II.

I think that technology now is the speeded-up communication, and all the messages are going too fast, and coming at you all the time. We have split screens, another SMS comes to you, there is no time in between, no time to reflect. And this also comes with text which becomes very mechanical and I wonder if we are not sometimes lost in translation by the machines, and we lose a bit of humanity. It is black and white, and we lose some details.

2 NEC screens and video 53-13/16” × 95-5/8” × 7-5/8” (136.7 cm × 242.8 cm × 19.3 cm) Edition 1 of 5 + 2 AP

No. 70768.01 @Michal Rovner, Courtesy of Pace Gallery, Photo credit: Annik Wetter

MR: I call this one “Nilus” which is the Nile in Egypt. I went on a trip with my parents to Egypt about 30 years ago and it made a very strong imprint on me and I saw all the hieroglyphs and statues. There were many hieroglyphs about jackals which is very important in Egypt and is the form of the god Anubis. So I filmed the jackal when I felt the world was in a state of fear from all the refugees on the move. And alongside there was a sudden manifestation of terror attacks in places where we were not used to having them, not in the Middle East but in London, Belgium, and France. And then I thought that the world was in fear and everyone was watching each other. There was a great deal of suspicion in the world.

So I sat in dark fields, and waited to meet the jackal, the other, the stranger. I wanted to feel the night, and to not be in control. We have always had the night but we have avoided the night, and nature. So finally the jackals came and one came very close to me. I had to film at night using night vision, security cameras, surveillance equipment, etc. so I became like a detective. In the context of the Egyptian hieroglyphs, they are imprinted on the jackal. And he is standing in profile, and he is something that we cannot control, in a good way. He is looking at what is going on with humanity right now, and the people are waving, signalling something and wanting to be noticed. Maybe they are signalling our conscience.

KK: We are animals, and art is one thing that separates us from animals, along with text. Is this a warning from nature that we need to change something, perhaps go back to basics?

MR: I think there is a warning. The jackal is watching us, and is concerned about what is going on.

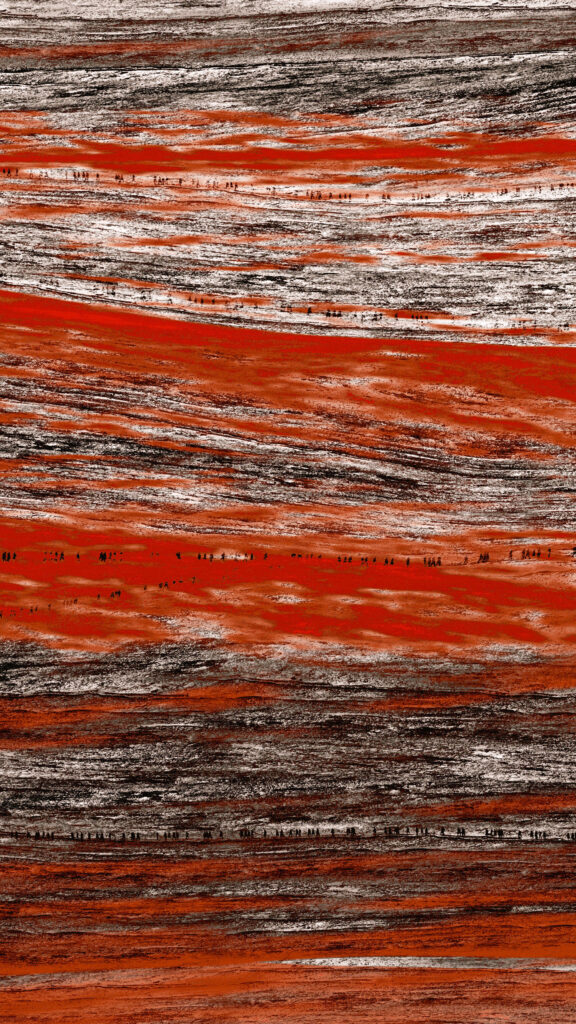

If you open up a television, in the back there are the wires and glowing pieces, and on the front there is breaking news, and you see the red lights in both the back and the front. This piece is made using heat cameras, filming people. It was white in the heat camera and then I turned it into red. Yes, we are being detected all the time. There are new codes, new ciphers all the time. Now the people are walking, passing each other, in a complex pattern. They are never moving behind the line, but they are passing through each other.

At Espace Muraille “Dislocation” Exhibition

Michal Rovner: The main statement I wanted to make here is about dislocation and people migrating, and I always film people and erase their identifying details so it could be people anywhere. I like0to mix them, and take them out of one context and throw them into another context. I like to mix footage from different places. There is always a question about identity and about place. Now it isn’t a question, it is an issue of identity and place. You see people every night on television in the news and you see faceless people moving in endless rows, sometimes hidden like shadows, where the landscape is almost covering up the people. It’s 70 million people on the move.

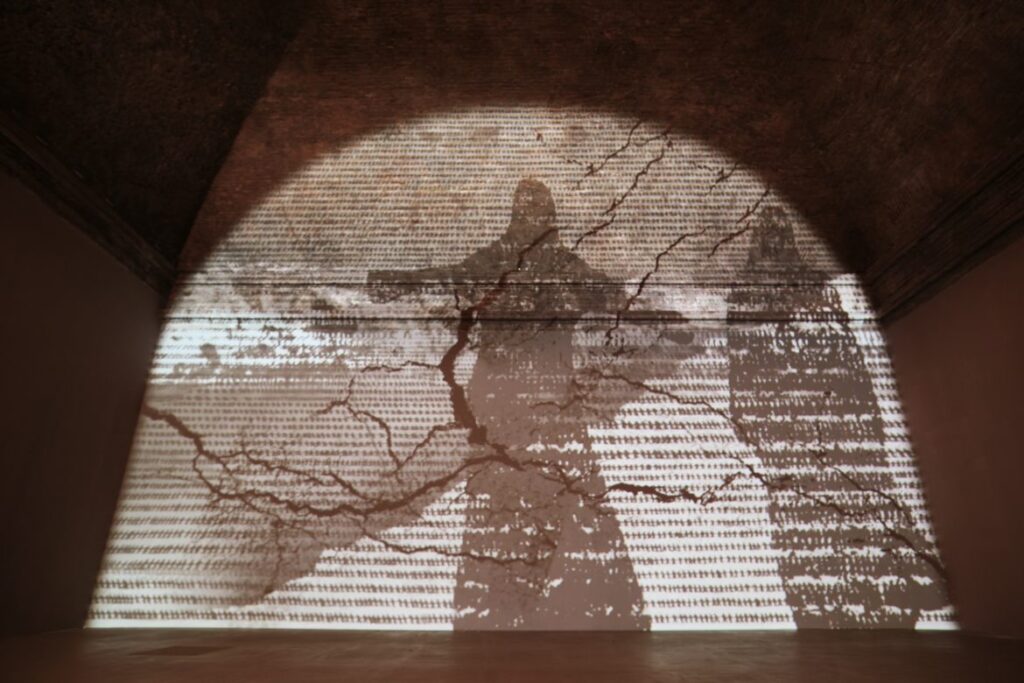

The trees are from Jerusalem and they bring the aspect of fluctuation, of human tectonic layers moving in the world. Not only because of the humans and dislocation of people but also about global warming, and ecological issues. All the structures are changing. The cypress trees also define the here and the there. They are behind the cypress, on the other side of us, of our home. They are them, not us. The question I want to raise is: are these people them, or are they us? And what makes them them, and not us? Fear of the other, of the stranger, is very powerful.

You might think there is a lot of progress and advancement, and yet we have homeless people on the streets. We could do something about it, about our fellow man. We need to have basic compassion for our fellow human. The people are broad strokes in my work, and they become part of the landscape. The landscape comes from barren hills, it is a lot of landscapes that I squeeze together. It also references layers of time, like archeology.

KK: Is there a solution to the movement of people and migration?

MR: There could be. Look at what happened in Germany. There they made sure that refugees were welcomed into society and now there are over 1 million refugees in Germany. I think if every country and every person could do something for another person or family, then we could solve the problem. You make a decision to leave when you are really desperate, and when you are forced to leave. It is a tragedy to leave your home. I think the hardest thing to confront is that something is going wrong, and you always want to believe that things will get better. It is very hard to be torn from your own place and your own identity. It is a big part of who you are.

This is a more narrative piece, it is a situation and an ongoing story. It is a five-minute reel, so it is an epic piece. The people are moving through the two women on the right. You see these women everywhere, looking over everything, watching. The music is from a sound editor, and I edited it. This piece needed music because it is such an epic work and the music rises and falls with the images. They create cracks, showing time is passing, and eventually the lines and cracks take over, and the people are gone.

Kristen Knupp interviewed Michal Rovner on January 30, 2019 in Geneva.