Nigel Cooke’s Oceans exhibition at Pace Gallery, Geneva, marks his first show in Switzerland and features five large paintings and three works on paper. Over his twenty-five year career, Cooke (b. 1973) has blurred the lines between figuration, abstraction, still life, and landscapes in his complex, layered and cinematic paintings. He has recently painted more abstract, monochromatic pieces on raw linen featuring dynamic, energetic brushstrokes.

These have been inspired, in part, by his daily swims in the sea near his studio. In a recently announced collaboration with Parley for the Oceans, Cooke has released a limited edition print of Oceans, the original of which is in the Geneva exhibition. 100% of the proceeds will help fund plastic interception, education and communication, material science and eco-innovation. As Cooke stated: “I have become a keen sea swimmer during this past year, which over time has forced me to consider the health of the ocean as an ecosystem. You are not an observer but a participant.”

Cooke’s work is in the collections of the Guggenheim Museum, New York, Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, Museum of Modern Art, New York, the Tate Gallery, London, and the British Council, among others.

© Nigel Cooke, courtesy Pace Gallery. Photo credit: Annik Wetter.

Kristen Knupp, Art Vista Magazine: When I walked into the exhibition at Pace, I saw the colour of four of the paintings and it struck me as Yves Klein blue, which is so powerful and vivid. Then I saw the fifth painting, Oceans, and it seemed very different to me. The show is titled Oceans, could you describe the show, and the inspiration behind it?

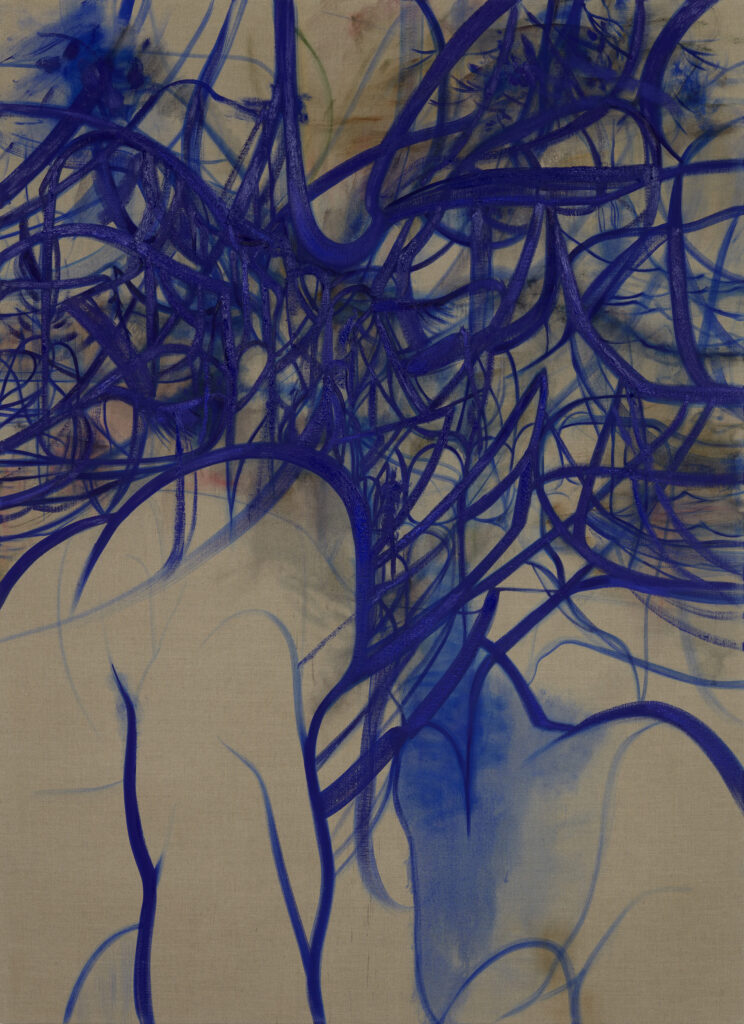

Nigel Cooke: My studio is near the sea, so I have a relationship with it and I swim in the sea several times a week, all year round. This year through lockdown, I’ve been working on paintings connected to the sea, the one I’ve titled Oceans being the first one. It is the work that holds them all together, in a way, and I felt like all the others are kind of like characters within that painting, that they in some part derive from that one. So the first painting is almost like the sea itself, and the other paintings are the beings existing within that sea, or beings that think about or look at the sea.

The other three paintings are named after characters from Homer’s Odyssey, but they are also mythic personas possessed of the energies of the sea. In the text, the sea is a major factor in what happens to the characters, how dramas unfold, how transportation happens and how the world beyond their immediate reality is accessed. So the sea is an image of what is beyond them, what is facing them as a challenge, something that may also deliver difficulty and threat, or may consume them. So I am interested in the mythic idea of what the sea is to a person, and a life, and how a life grows from youth into adulthood and then old age.

© Nigel Cooke, courtesy Pace Gallery. Photo credit: Robert Glowacki.

The lockdown was part of that too, not seeing family – my parents are a long way away. In The Odyssey, Odysseus is trying to get back to his family too, through various adventures, so I related to him metaphorically. Combined with the swimming, his story became a metaphorical North Star for me, how you romanticise an inner vision of the sea – there was a to-ing and fro-ing between the two, the painting being a kind of gateway between ideas and expanses of water.

My painting Oceans has a greater variety of tones than the others, as there are different oceans with different temperaments and temperatures, different geographical areas, so they are all combined in a sense, bound together in one painting. It’s an idea about what oceans are for you as a soul, as a being, including the political side of that too. I am also aware that oceans are arenas for hope and disaster for struggling people, particularly those who are desperate to get to this country from mainland Europe. Being by the coast you can’t help but think about the people who don’t make it across, but need to get across, and have come up with all sorts of terrible, last-ditch solutions to try to get here. It is the notion of oceans as a sort of universal, timeless, ever renewing area of hope, disaster and death.

In the other paintings, the blue is different because it is a little bit more of a cerebral concept. The Oceans painting has a tonal scale of almost black to sky blue – it has a slide from the depths to the spray, it has a range. I wanted the other paintings to be almost recessional, also dualistic – the blue sinks and is dark but if you stare at it, it becomes bright, there is a sort of oscillation. I wanted them to be pulsing, like a living being. Using a blue which is not a descriptive blue, because the sea isn’t really that colour, it becomes sculptural, a living sculptural form rather than something that is more descriptive of what light on water could look like, say. It is like an inner kind of water. So these three are more closely related, but the fourth is different, which is Calypso.

© Nigel Cooke, courtesy Pace Gallery. Photo credit: Robert Glowacki

KK: How is Calypso different from the other paintings?

NC: I try to wear my ideas quite lightly, I go to the canvas with ideas but they are intuitively acted out, quite performative. I am responding to what happens as the painting unfolds, and I try to hold as little as possible of a strategy in my head. But things like the colour and the form take on a huge significance, they take the painting in a completely different direction, even with small tonal changes. Even something simple like starting with a pink ground gives it a completely different aspect, even if it ended up blue, which is what happened with Calypso. Starting the painting quite pink and then it becoming overpowered by blue, it took on a dual kind of life, a tension. It took on a subversive persona like something behind it was trying to break out.

Often what I am interested in is those abstract properties of painting serving as meaning gateways, almost being the real image in a way. You may think about how they give an image a certain flavour and personality, in this case maybe that is more devious and treacherous than some of the others that look more innocent. And those are just the mechanics of the colour and the marks, it is something you can’t really define.

In the story of The Odyssey, Calypso traps Odysseus on an island while he is trying to get home. Or it is stated that he is trying to get home, but you don’t really know that for sure – it’s possible he may be having a good time on the island and trying to delay his return home, who knows? There is something ambiguous about it, it is not clear. The ‘surface’ story suggests he is unhappy about it, but it is not firmly established. In my painting there is something menacing about the pink, and that was a difficult thing to pull off, because that is not how one usually thinks about pink. Before the 20th century there was not even a name for pink, it was light red. It is a recent thing that pink became associated with femininity. These are things that inform that painting. I have three daughters, and ideas about what gender signifies is often at the forefront of my mind, and all of this went into the mix and created a circuit, in a way. Rather than a fixed idea, it is more like spices in a dish working together. The cocktail of things that came together earned the name Calypso, because it glued several disparate thoughts and feelings, or tensions, together in my head.

KK: Can you talk about the other three paintings a little more?

NC: The other three paintings have Homeric names too, Telemachus, Odysseus and Athena, and there is something each of them carry from The Odyssey, but also something they bring in from the outside, from the observed world. Those three have a certain staining in the background which is kind of an emanation from afar, like a landmass seen far behind them. I noticed with my swimming as the summer started to fade, the sea got colder, and the land across from where I swim started to take on different visual aspects. I make watercolours by the sea after I swim, literally 10 seconds of colour notation, and I built up a visual diary. I tried to honour those in each of these paintings. There is a second colour that tries to break through in each one of the paintings. One is a gold, one is a green, and one is like a red. They were from these notations I was making, and in the studio they started to provide other characteristics for the image – one was mature, one was more innocent and child-like, one was more of a hybrid, so that one became Athena, the Muse of Odysseus who transforms many times in the story, often into an owl.

She is powerful, but also democratic. I wanted that figure to be like a female bird of prey, a female goddess, and also a hero. Not really a person, but with elements of a person like arms, shoulders, chest and neck. But also a beak, a predatory eye, and a willowy falling of water mixed in too, obscuring and erasing the forms. Tranquility and turbulence.

Those things are difficult to put together in a straightforward picture. Focusing more on line, I can move from a descriptive border of a form, then to a recessional space, to a painterly modelling and back again, between description, modelling, boundaries and spaces, without there being any ‘meat’ on the image. It gives me great freedom to chop and change between what I am talking about. I can go from saying this is the edge of a landmass, to the side of a head, to wet hair falling over an eye, to an owl’s eye socket, to a beak with blood coming out of it, to the shoulder of a woman, to the waves of the sea.

I can use a line to move between those descriptions. That is the freedom I am looking for because I am trying to capture how poetry works, in a way. How in a tiny space you can move across great distances in space and time. You can go inside someone’s head, outside it, across the world, back in time, inside a different species, different perspectives, you can move like that in a moment. That mobility and flexibility is what I want from painting. It has taken me thirty years to get to that. The last two years I feel like it is actually starting to sing the way I want it to.

KK: How does it feel to have your work in Geneva, and not be here to see it?

NC: It is actually the second time I have had a show this year that has been this way. It is starting to become more normal, and less of a surprise. I was looking forward to coming but I had some expectation that something would block that. It feels very odd to not see them together, and I was looking forward to celebrating it. This year has been very mixed, there have been terrible things, but on the local level my work has gone out into the world, so it is a contradiction. I’ve never shown in Geneva before and I have always wanted to go to Geneva. Hopefully I will come in December, so I haven’t given up hope yet.

KK: You have changed your style quite a lot in the last few years from more pictorial image-based paintings to more abstract work. Are you happy with your newer work?

NC: I really am, because it is a time of life issue as well. I am not particularly old, I am 47, so there is a certain reckoning around that age. I have established something, and I can now go anywhere, I have freedom to choose. I might not have that many more breaks like that. If I look at all the artists I like, around that age is when they started to make the work that they then did from then on. I am not saying that I want to settle on something. I went to New York when I had reached an impasse in my work. I wasn’t connecting with it. I was executing it but it didn’t feel like how I felt. The speed was wrong with my thoughts and my feelings. I felt like I had lived a lot of things, and there was more that I needed a painting to absorb. I felt like I needed to say less, and absorb more, and be more. To be more and not talk about it in the same way. I felt the pictures were working so hard to talk about all these things, but it was almost like using words. Like trying to write a novel to describe a poem. It just felt like the wrong fit for where my personality and my thinking had arrived.

When your paintings and your life don’t match, that is a crisis. This is probably the second or third time I have been in this position, but it was make or break this time. How do I maintain something that is inquisitive, joyous, celebratory, and real and true and risky? How do I get that thrill of the risk, and the delight? I wanted a painting that I could live or die by, that wasn’t endlessly polished. I hack through the painting in the moment, and I wanted all the vulnerability of that to be laid bare, and be honest about how they were made. I want to show the whole working out, and expose it like an X-ray. To have it hanging and have the experience be the image and not a bullet-proof veneer of skill over that experience. I started to feel that the ending was the moment when I let go, but now I feel like I am constantly involved and the painting is a living thing. I think that is more the kind of person I am. I like to have experiences and be in the moment and try things out.

© Nigel Cooke, courtesy Pace Gallery. Photo credit: Robert Glowacki

In New York I was thinking about Clyfford Still or Rothko, if you look at their old work, there are little Rothkos in between those figures. Under the arms, the necks and the heads, between the chin and chest. Clyfford Still is the same, under the plow, the arm, there are little Clyfford Stills everywhere. I wanted that, to drain out that core thing. I worked at the studio day and night, and one night something finally emerged. I was reducing and reducing and reducing for about a week and then I ended up with a line that just spoke to me. From then on, I developed it and felt really vulnerable, exposed, away from home, and just lost. I felt adrift, the metaphor being lost at sea being a key memory. I realised how much ocean metaphors are part of how we discuss being beyond our comfort zones, psychologically. How the ocean is a metaphor for psychological bravery. I wanted to celebrate that time in my life, and I was able to do that.

KK: It must be very satisfying to try something new and have it be so successful, has it given you confidence to try new things?

NC: Absolutely. Art is all risk – if you know what you’re doing it isn’t art. That is the job. I have had ups and downs, and my fair share of kicks in the pants. You have to build a thick skin to take the gamble and take the risk. I tell my kids: when working creatively, you have to make peace with the worst case scenario. If you can make peace with that, then you can jump through the window, you can be free. That is what the culture demands of you, particularly now. But the evolution of my work was also about appropriateness. As the world changes, the world needs a different kind of art. I am not saying it changes the world, but it must have some hope for that, a tiny fragment.

All of this was in the middle of a dark time, and I was thinking about fixed, concrete, figurative images, they started to feel distasteful and I could not work out why. Then I realised there are too many people amongst us, those in power, who claim to know things, and insist that they are not connected to nature and everyone else. But a person is a network, a wicker basket, rather than a lump of lead or marble. It is a complicated mesh that can break and fall to pieces but also connect to other ones and be part of others and part of nature. That was the driving force for this change.

I asked myself: What is the painting that I should make in 2018, 2019, 2020? It is a distaste for the concrete and an embrace of fluidity, empathy, the ebb and flow of things, and responsibility. The viewer is responsible. It is an invitation to the viewer to look at things and decide together what it means. It is a more liberal mindset and that has to be what drives a picture for me. The point where my ability can take off and where it can collapse are co-dependent and both are important. I am not going to sugar-coat the process, pretending that it is perfection. I want the dirt, and the stain, and the revisions, and the reverse-steps to be part of the image because that is the human energy of the image.

© Nigel Cooke, courtesy Pace Gallery. Photo credit: Robert Glowacki.

KK: Speaking of human energy, I read that one of the things that influenced you is ballet and particularly Olga Smirova of the Bolshoi ballet. She said “The skill of listening to yourself, this sense of proportion, this knowledge and experience help you make each individual decision. That’s what makes us different from ordinary mortals” Can you relate to this statement and does this type of thinking affect you and your work?

NC: Well that says it all really. I only recently discovered her in Swan Lake and I was transfixed by how the swan mutates. How this is embodied, in the muscle, the twang, frequency and tonality of the muscle changes – she literally looks like a different being. The body is used in an entirely different way from the black swan to the white. And I thought: I want that, I want to be able to work like that. All the best art has to do that, be both swans. Not in contrast, but in some sort of loop and dependency, a beautiful balletic connection.

The fact that she embodied that opened a door in my mind. She talked about the extra-human capacity she is trying to tap into, and that is what a painter does too. The performative aspect of painting is when you start off drawing the figure, the nude, the landscape, and you are training that muscle. In the end what I came to is that the muscle doesn’t need to keep saying the same thing. All the intelligence is in that arm and you need to let it just be, and as your thoughts change, it will change. Little changes will come in and they will take it to a new arena. She is still the same person, but those little modulations take you to somewhere completely different. I wanted to have faith in the muscle. Go to the canvas with nothing because it is all there, an inner vocabulary. I don’t look at pictures, photographs, it is all from within. That set me free.

KK: In terms of the process of making paintings, it used to take a few months for you to make a painting, and now is it a shorter timeframe? How are they made, do you leave them for a while and come back to them?

NC: They are less time intensive, and they are done in one relationship. I don’t really break away from them, once I am painting on them it is every day until it is done. Maybe in the final week there are a couple of gaps, but essentially it is about the paint remaining pliable at that time. There is a bit of layering that goes on but it is all in one cycle. I wanted to close the gap between the time I spend on the painting and the time the viewer spends on it. To close that gap is more invigorating, and the viewer will get more from the painting I think. They would pick up more of the incident. That level of incident is the excitement and I wanted to gift some of that excitement to the viewer. A lot of that is about things dripping, splashing, halting, colliding, brushstrokes that crash into each other. There is something very foodie, even sexual about it all. It is very bodily, like weather. I was killing all that before.

I stand by that other work, and it felt important then. At the time I wanted paintings to be things you could always get lost in and find something new. There was a reasoning behind it, the idea of all that information and detail was almost like a film. You can’t see all of a movie in one glance, it happens over time, and I wanted my painting to be like that. But I changed my thinking about that and I wanted it to be a sensory experience. I suppose they take two to three weeks to paint. If you can’t make a painting in three weeks, you are probably painting another painting on top.

© Nigel Cooke, courtesy Pace Gallery. Photo credit: Annik Wetter.

KK: How do you know when a painting is finished? You’ve said there is a “sense of rightness” about a painting and that was when you knew it was finished. Do you still have that feeling now?

NC: I do have that same feeling but I have also tried to get the courage to look at that feeling in different ways. So the rightness could be wrong, and a bit ugly, but still feels right. It is a balance between elegance and ugliness so that you redefine beauty. It is like trying to find an idea of beauty which is more complex. It is also whether it captures that experience of the making. Some of the flashiest, most skillful paintings are very satisfying straight away but after being in the studio for six weeks they just go away and stop giving. Maybe they have been over-worked, over-painted or under-painted, but they just haven’t hit the balance. There is a kind of fine maths to it that I can’t define. There is just enough but something held back. And then I know I am fired from my job. You get the sack, fired, made redundant, you aren’t needed. Good or bad, it is walking away from you.

KK: How did you cope under lockdown, creatively? Did it help you, stifle you, or was it good to have that space with no interruptions? Or was it a mixture?

NC: I would say on the whole it was harder. At first I couldn’t really work at all. I did a series called Midnights during the first lockdown, because I could only really work once everyone was in bed and it was dark. An artist is a lockdown-type person anyway. I am always shutting myself away and trying to concentrate. But when everyone is doing that and trying to be creative themselves, whether it is baking, gardening, crafts, there is a sense of it being flattened. My isolation was like everyone else’s, and I needed a bit of tension. I needed an edge, I like to be out of step. I like to feel like I am doing something alternative to the general flow of people’s time. So I came to the studio at night and that unlocked something.

This show in Geneva is like the big brother or sister of that Midnights show. They were a series of six works on paper in a muted palette of blacks and blues. So that was my response to lockdown. I reduced it down and worked in a narrow frame, at night. So the blue became about what was outside the window, and talking to the darkness, and the inner idea of darkness.

So with this series in Geneva, I wanted to do the same thing but with the sea. I used to go to the gym, but with the lockdown I found sea swimming and that became my exercise. Then I realised the relationship with painting. Every time I went to the sea it was different. Sometimes it was rough, raining, or sunny and hot, but I would do it anyway. That was a bit like painting, doing it anyway. It was almost a mirror of the lockdown work, with the sea. I always found ways of doing something, but during the first lockdown I was exhausted a lot. This time I feel ok and I can carry on.

KK: What are you working on at the moment?

NC: I am working on more works on paper. The materials with works on paper have to be just right. The ones in the Geneva show are on little exercise books from the 70’s, so the paper is a certain faded, greyish shade of white, with a board that gives it a hard edge. There is something about that I really loved. And the Midnights are on paper I found in New York. So to go up another size, I have to find another paper again. So I am trying to work out how absorbent the paper is, how the paint sits on it, what colour the paper is. There are more of these large paintings to come, but I will take a break and work on paper for while.