The International Red Cross and Red Crescent Museum is currently showing the Concerné.e.s/Concerned exhibition of the work of thirty student artists from the Geneva School of Art and Design (HEAD). From these pieces, two students will be selected for the prestigious Prix Art Humanité. This prize was established six years ago in 2015, and is organised by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), the Geneva Red Cross, and HEAD to award a prize to a graduated student in Design or Visual Arts whose work connects with the relationship between art and humanity.

Art Vista’s Kristen Knupp interviewed Julie Enckell Julliard, exhibition co-curator and director of cultural development at HEAD, along with Philippe Stoll, exhibition advisor from the ICRC, and artist Zoé Aubry, whose work is featured in the temporary exhibition, and who was also given carte-blanche access to “hack into” the museum’s permanent collection to create a piece that interacts with the collection.

Art Vista: There are thirty artists in the Concerné.e.s/Concerned exhibition, and how are the winners for the Prix Art Humanité chosen from these artists?

Julie Enckell Julliard: There are always five finalist nominees for the prize, and then two win. There is a jury from different parts, the ICRC, HEAD, the Red Cross and two external members. They see the thirty proposals and then they vote on the winners. Also, during the awards ceremony, the audience votes as well, so it is a combination of these things. The five nominees have to pitch their work in front of an audience of 400 or 500 people, so it is a very good exercise for them. They are very young and not used to doing this kind of pitch. The jury then decides based on the presentation and the dossier of the artist’s work.

Philippe Stoll: The idea of the prize is to try to encourage artists or students to consider this part of the world, the humanitarian side. There are so many things that young artists are exploring or thinking about, and I wish there were more artists who try to understand and question and push boundaries around the subject of humanity and humanitarian issues. At least it opens up this area of thought. In Geneva, the students are studying in the biggest and most important humanitarian hub in the world, so they should be engaged with this part. That was the thinking behind the prize.

JEJ: What is interesting is that they don’t work on humanitarian actions which are far away, in complex, abstract situations. They are students and so they focus on topics that are close to them, such as neighbours, women who have been murdered, things you live with. So this part of society is emphasised by them. They pay attention to the humanity of daily life and not really the actions of humanitarian organisations. And what you can see from this exhibit it that humanitarian action starts here, in our daily lives, so it is not separated and something you have to travel very far away from here to do. You can already pay attention to what is happening here.

Art Vista: I think it is a wonderful prize and it makes sense to have this in Geneva given its role in the humanitarian sector.

PS: If I can add an element from us as a humanitarian organisation (ICRC), is the desire to better engage with artists and move away from what we have done in the past. In the past, we would use artists to complete certain projects, for example, a calendar, where we would order photographs for this project. On the other hand, I have artist friends who contact me and ask if they can have some money to travel to Zimbabwe for example, and we don’t give money to artists. So with this prize, we can reconcile the desire to work better with artists and have a real exchange and dialogue on humanitarian issues. This is a place where you can create bridges between the work we do as the ICRC, and the issues in the humanitarian sector, and with artists who have freedom to express their thinking. The topics, the reflections, the thinking, are very interesting.

Art Vista: What are the outcomes that you would like to see from an exhibition like this one, which features the work of young artists?

JEJ: We want to gather the artists here in order to be taught and learn from them. They tell us about gender, about the body, about sexual violence, the significance of certain clothing, etc. So for me, it is a big opening and a way to bring a lot of questions together. It is great to have these bridges between the artists and the organisations.

Art Vista: What about engaging with the public and perhaps the younger people in Geneva?

PS: We have ambitions to better connect these two worlds between the artists and the humanitarian world. We have a symposium online, which tries to connect art and humanitarian actions, so we had an event two weeks ago about how ancient Greek theatre can help to cope with post-traumatic experiences of witnessing the horrible acts of war. We also had a paper presented on the impact of Caravaggio and the representation of suffering in contemporary photography. So suddenly you realise that there are many bridges and we would like to continue to shake these two worlds so that they come together.

Art Vista: How can you increase the impact of this exhibition and prize?

JEJ: We have an idea of what humanitarian action is, however, the artists don’t use these images, they use their own experiences to connect with the topic. There is a complexity to the issues, and they are not just overseas somewhere abstract. With art, we need to put some more complexity and nuance in this field to make them match the dialogue better.

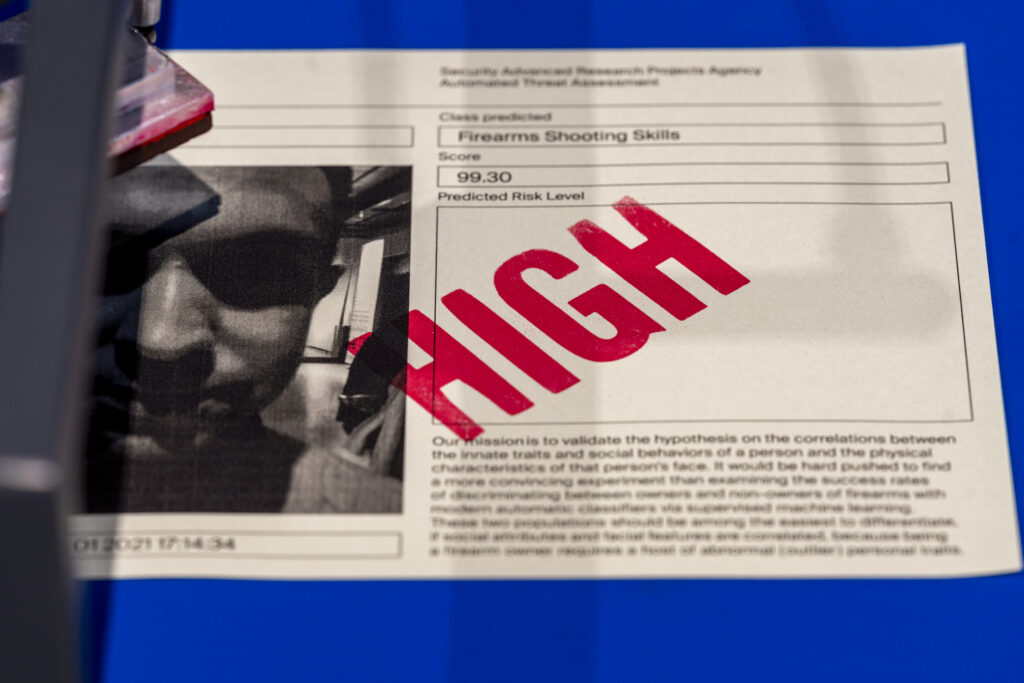

PS: One of my dreams is to have more art in places where you don’t expect it to be. Such as in conflict situations, or in conferences or other unexpected places. For example, with the work of Marta Revuelta who won the prize in 2018, we have “The Logics of Droning” (this piece monitors visitors movements by a drone in real time and then assigns a profile to each person: combatant or civilian?). She came to two conferences and it is interesting to have her there. In December 2019, she presented at a conference with 3,000 people, including diplomats, heads of state from 180 countries around the world. And this installation was there to bring a different element to the question of data protection, artificial intelligence and so on which are complex issues. With her work, you feel it. At a big conference, where the rules are very precise, her art has an impact which is a bit disruptive.

Art Vista: What were some of the surprises this year with the exhibition and art prize?

JEJ: This year we added an additional prize in Senegal, and we wanted to organise a big event there but because of the situation with Covid, we couldn’t. We managed to give the prize anyway, and we awarded the prize to Yace Banks (she is a feminist photographer has been documenting how women in rural Senegal live). It was quite tough to organise. We would like to carry on with this and have another edition abroad next year, but we don’t know where yet. For this year, we will have the ceremony for the new prize in October 2021.

PS: I think this work from Senegal resonates a lot with the debate we are having in the humanitarian sector about who owns the narrative. Zoe Aubry’s work is also a lot about that. In the humanitarian sector it is not about who has the power, but about who tells the story, and this prize is exactly about that. The jury is based in Dakar, the people based in Dakar own the whole process, and suddenly you have a different point of view on things that concern everyone. So it is not the West being concerned about people in the South, it is showing that the whole reflection happening in the art world as well, and politics. So this is accelerating the momentum. The impact of the prize in Senegal was very well received and they will continue with the prize.

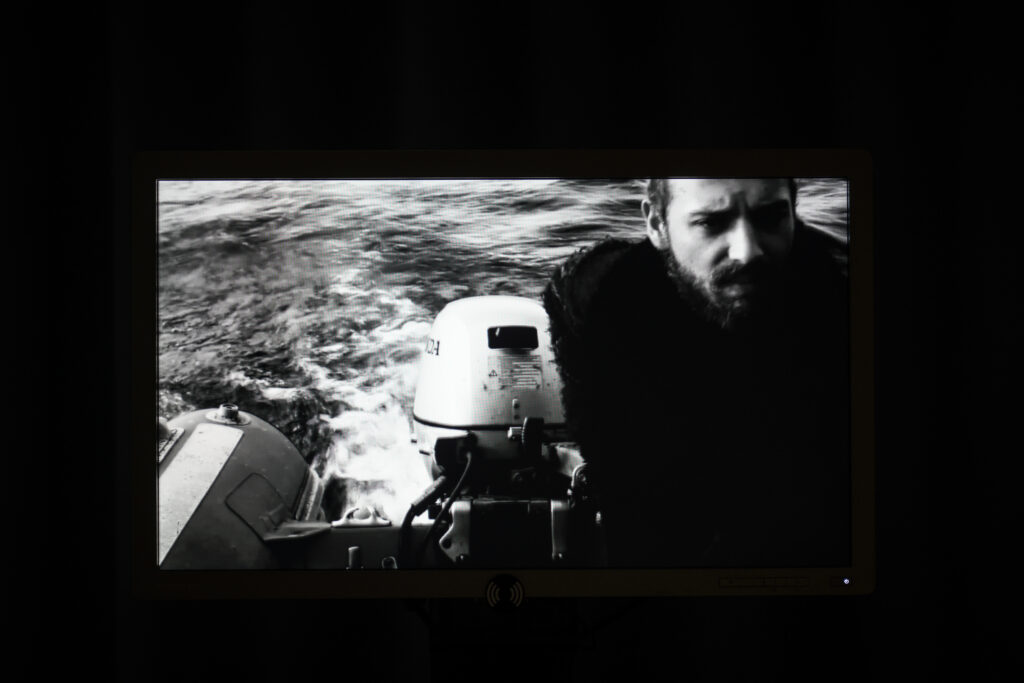

This film by Rokhaya Marieme Balde “Finding Aline” is also about a non-written story and the author is trying to write the story. It goes back to the humanitarian crisis and who says what is the truth. For us as an organisation we don’t want to know who is responsible, but who needs help. And it is very difficult to find out space in places like Gaza for example, because we are just here to help those who need it. The narrative of the story is so important to find the balance between propaganda and the truth.

Art Vista: There are so many wonderful young artists in Geneva and Geneva has a unique art world with its own characteristics. How can we lift up the young artists in Geneva and give them more opportunities to have their voices heard and give them more visibility?

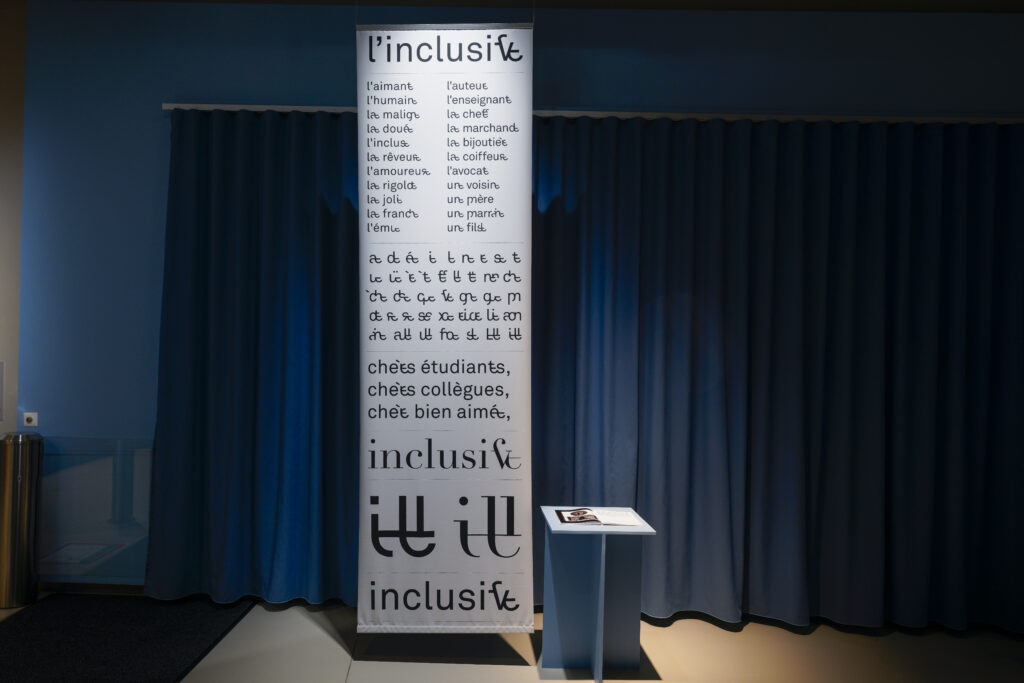

JEJ: Sometimes you can control that and sometimes you can’t. For example, the amazing work of Tristan Bartolini (L’inclusif-ve offers an alternative to the gender binary system within the French language. Bartolini was the 2020 winner of the Prix Art Humanité) was a worldwide success with more than a hundred articles and broadcasts about it. It touched something so important, and it went viral. This is something we did not necessarily anticipate, but it was very welcome.

PS: Several of the artists got additional recognition after they were in the prize, for example, “Finding Aline” was given the TENK Award at the Visons du Réel film festival in Nyon in 2021, and the website for women’s pregnancy issues received funding from the Fondation Hans Wilsdorf. Maëva Weissen, who was the winner in 2019, upcycles football jerseys, a symbol of masculinity, into women’s clothing, and was featured in several magazines. The work is so good that it leaves HEAD and the exhibition, and goes out into the world beyond the prize.

Art Vista: Is that the goal of many of the artists who are shown here to have museum shows and gallery shows beyond this prize?

PS: For some of them it is. In this work of Dorian Sari, which has been shown widely in the art world, you have so much information and a real ability to touch people. Art is something where you can provoke a reaction, a “déplacement”. Maybe 90% of people will not understand a piece, but 10% will be interested. It is also interesting to bring art pieces outside of the art world, and there is a big dimension of how art can be used by the people themselves to create memories, to uphold themselves, and bring dignity to themselves. And these issues are sometimes not focused on very much.

Art Vista: It can also stimulate feelings of empathy with people, for example in Dorian’s video, it describes the feeling of leaving and not knowing where you are going, and having to make decisions without having all the information, a bit of the experience of being a refugee. I think it is really powerful.

Zoé Aubry: I think it would be wonderful if art could change the world, but as Julie says, we tend to attach our gaze to things closer to us, and we need to stay humble. It is also part of the work to deconstruct the idea that one piece of art could actually change humanity. So it is bit of disillusion but we need to be connected to reality.

Art Vista: Can you talk about your work, Zoé, on femicide conjugal (domestic violence) and what has been your motivation behind making this photograph, “Estelle Veneut – Badr Smati”?

ZA: The first time I had a big solo show with this work, I engaged in discussions with relatives of murdered women, and there was a real impact in the facts of the case because we talked about the case and a relative realised something from reading the text from my piece. She realised that this violence resulting from a system of oppression discriminates and destroys on a daily basis, in particular the way in which the justice system only reacts – and even then – once the person has died is not just history, but is something that touches people universally. So she decided to testify in the case. So this is for me the biggest impact that my work could have, to connect things together and change reality.

Art Vista: But that is what will happen. People will see your work, and the subject matter and they will be changed by it.

ZA: This is why we have to be involved in super small issues so that all together we can make a change collectively.

Art Vista: Yes and global changes start with small changes. For example, the

“Me Too” movement started with one person posting about their experiences.

PS: I don’t think that one piece will change the world. But if we don’t do it, it leaves space for others to put their views forward, so it is about occupying spaces. And one piece will connect with something else and then slowly an impact builds up. At the ICRC, we have been trying to impact how people behave in war, and when I was talking with soldiers at check points, I doubt that I will change their views overnight, but with me going more than once, alongside other people, then changes can begin to happen.

JEJ: It is also about creating an image about something that doesn’t have one. For example, the piece by Ciel Grommen about North Korea and South Korea is very poetic because she addresses the border between the two countries, where they wanted to create a park but it wasn’t possible. So she made a piece of the nature that should be at the border. Art is about giving an image to something where there is nothing.

Art Vista: Can you talk more about your work, Zoé, and this photograph – I understand that the ink it is printed with will fade over time – is that correct?

ZA: The image I printed is from a newspaper. I asked the printer to print it on a type of paper that doesn’t absorb the ink, so it is really a live piece that changes completely from the day I printed it up until the exhibition ends. I think it is interesting because it destroys itself so that is part of the process. It is the first time that I have shown only one piece from the series about femicide, and it is a new piece and the only one in which we can see the murderer. Because of the process, he disappears, so that is quite an act of revenge. The other images show people who should have been concerned, like the police, who came to the house after the crime, but they didn’t react before the murder. So I impact the photographs of those people, and it is an extremely violent process.

The little girl, the daughter, who witnessed the murder of her mother, is the only thing that keeps going, alive and visible in the picture.

Art Vista: The fading process could be seen as a metaphor for all the lives that are impacted by a murder like this; the woman, her daughter, also the murderer; all their lives have been changed. I also like that the piece is on small pieces of paper, like a mosaic, and it is fragmented.

ZA: It was partly for practical reasons because it is so large and the print process destroyed the printer so it would be too expensive. I also tried to connect all the spaces, all the stories and facts together, to try to speak about the collective and global issue of femicide conjugal. And how art could or maybe can not change something alone, but maybe working together, it is possible. So to have a a lot of pieces that connect together to make one image is important.

Tell me more about why you have decided not to sell your work, because this is an unusual stance for an artist.

ZA: I decided to do this before I could show the work from the series about femicide conjugal because it is a question of ethics. I worked for four years on this subject, and it affected me emotionally, and I was not comfortable with the idea of selling these stories. I was also actually surprised and disappointed that someone could actually consider having these pieces in their living room. The first step I took was to establish an association for these women, so that any funds raised by my work could be helpful to the women impacted by violence. In reality, only museums can show the work, because they will not sell it, and by showing it they can help raise awareness about the issue.

Art Vista: About your other work, “Watch Your Credit”, I understand that the museum has thousands of images and documents in its collection and yet you decided not to use any of them in your work for this exhibition. Instead, you focus on the envelopes and packaging that the photographs were sent in. Can you explain why you decided to do this?

ZA: There are really beautiful photographs in the collection that are really problematic, through my gaze, as I speak only for myself. I was interested in the archive room of the museum, but I really didn’t want to re-visualize something that was problematic. I thought the best way to not impose this on the viewer was to not show it. I decided this while viewing the images and documents on the rotator, which is a big machine where all the materials are suspended, and I read everything there.

I read all the conversations about how to raise more money, how to choose the images, how much the museum paid for the images, and if they had the reproduction rights or not. I decided to only work with the photographic credit and the envelope that was sent to the museum. On these pieces you have so much information, like the address of the agency, the name of the photographer, who is likely a cis white male, who takes photographs in foreign places where he is a visitor, etc. I decided to put the photo credit of a photograph with a woman in it, where she is a mother figure shown after an explosion. So it reflects the views of the photographer, and what they wanted to show.

It was quite difficult to realise that there were no female photographers in the collection, and no local people involved in the production or the selection of the photographs of themselves. The reality is constructed by the photographer. My piece asks the viewer to do some of the work themselves to understand the meaning. So the title is “Watch Your Credit”, which is a bit of a putting the museum on notice.

Art Vista: Is the museum updating or changing their policy on collecting photographs?

ZA: I am not sure, but the archive room where I was working is kind of a museum-like space which is not currently being added to. I also collaborated with Odile Blanc who is doing her thesis in History on these archives. I collaborated with her and the artist Angela Marzullo to explore this topic further.

Art Vista: Is there anything you would change or do differently if you could with the pieces that you made in this “carte-blanche” assignment for the museum?

ZA: I just adjusted it last week! Because it is now sitting on top of archive boxes, and before it was on the ground in the path of visitors, which I planned in order to disrupt them. I didn’t expect that the public would behave as they do, and they are apparently not always looking where they are going. The pieces were getting destroyed, so I needed to raise them up on the boxes so that people would see them more easily.

Art Vista: I really like your message, but I may have chosen to use the images to make the point…

ZA: But you already have the images here, because you know what they look like in your head.

Art Vista: It is really brave, because, to be honest, it is not visually beautiful…

ZA: I know! This is something I do in my work, I try not to embellish reality. The materials I use are cheap and connected to the subject that I treat. For my other work, it is cyanotype on cardboard, and the pieces are already broken through because you have to put water on it. This is something I try to do more and more. I want to be closer to the subject and not be part of the art market.

Concerné.e.s / Concerned: 30 artists on humanitarian issues is at The International Museum of the Red Cross and Red Crescent (MICR) until 26 September 2021.