Nacoca Ko’s work at the L’effet Ferdinand exhibition at Espace L in Geneva represents a counterpoint to the other pieces on display. Through her digital pieces and performances, Ko brings a feminine perspective that responds to work by Fernando de la Rocque and Ferdinand Hodler. Her AI-created images embody a quasi-future exploration where virtual images expand and bring to life a new cultural narrative. By asking questions about the influence of technology on our imagination, the artist moves between digital image and video to investigate our experiences of reality. As Nacoca states: “Our global culture is woven from will and imagination – the ideas of our minds that create, for example, a chair, a social media community, a food redistribution program, a spaceship, a mine for raw materials…Our cognition is expanding to affect every semblance of existence on this planet. As we question the sustainability of our current systems, I find it very compelling to look at new ways of “thinking thoughts,” “worlding narratives,” and to dream dreams. How we operate as a nexus between technology and nature will define the perpetuation of our society.” Art Vista Magazine’s Kristen Knupp met Nacoca Ko to discover more about “worlding”, creating AI images, and cyberfemininism.

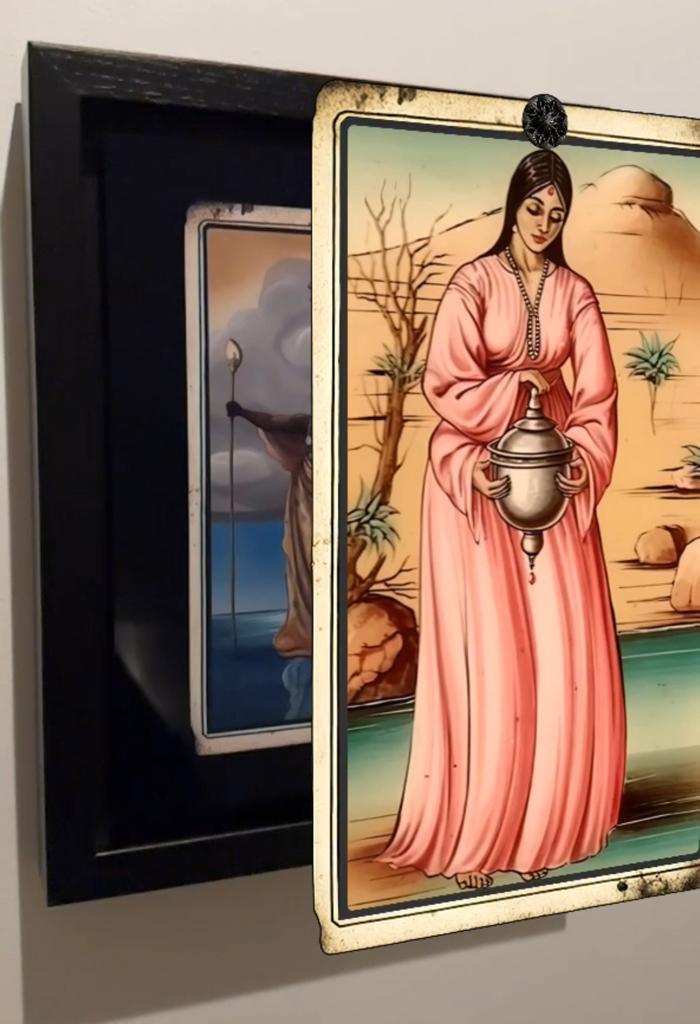

Nacoca Ko, Power comes from a soft place, L’effet Ferdinand exhibition image at Espace L, photo: Guillaume Collignon

Kristen Knupp: Could you describe your show at Espace L, where you have a framed still images on the wall, a QR code where you can enter into the image and it is all in dialogue with pieces by Ferdinand Hodler and Fernando de la Rocque.

Nacoca Ko: As far as the dialogue goes, originally it was Fernando de la Rocque in dialogue with Ferdinand Hodler. So both these artists have a male gaze relating to the themes that Hodler often explored; symbolism, parallelism, the spiritual, and the female form as well. While, in contrast, my aspect is the feminine side or regard, looking at it from a more personal level. The work I am showing at Espace L started to take shape earlier when I was asked in Basel to do an event. Usually my work uses technology and talks about our place in deep time, and I think about speculative futures where I imagine the post-anthropocene world, meaning a world no longer focused around humans, and our relationship with nature, as well as technology’s relationship with nature.

This work, however, is more personal, and is focused on my identity, especially in relationship to the internet where identity can be fluid, or aggrandised into a persona. I was also having a hard time with the concept that being a feminist is related to being strong like a man. I wondered how I could be strong as a woman and have my own sources of strength. I looked towards ancient heroines that have been erased from patriarchal religions, and looked at different spirits that are feminine forces. I was also inspired by Jungian archetypes such as the trickster, or the great mother who is related to creation and nature, and the old crone who is wise. I looked at different stages of life, and these are all part of me and I carry them with me.

Nacoca Ko, Power comes from a soft place, L’effet Ferdinand exhibit at Espace L.

KK: How many images are there and how were they built?

NK: There are eight images including the architect, birthing, child, teenager, seductress, motherhood, working woman, and shaman/older wise woman. They are related to the concept of “worlding,” through the narrative. I am inspired by the philosophy of Federico Campagna who encourages magical thinking and said that once the apocaplyse comes and the landscape is burned, then the land becomes very fertile for the new world. I feel that we are in an in-between moment, and rather than just be overwhelmed by the singularity of progress, for example, with things moving so quickly such as with AI, we can think about what the world looks like that we want to build. “Worlding” has many different connotations but can mean creating a world online. In some of my virtual projects I have created worlds that you can explore online.

KK: How does your work in technology connect with feminism? I have often heard that the online world is quite male-dominated, but you are using it to connect to your femininity.

NK: In this project, I am calling for reintegrating feminine aspects into ourselves. So rather than getting caught up in progress, to take the time for typically feminine things such as nurturing, being in touch with nature, being more receptive. I think there is a call for that, in terms of our culture, and that it is starting to shift. Technology has the capability to bring out the user’s feminine side. There is a whole movement called cyberfeminism that was somewhat inspired by the work of Donna Haraway, a professor in the History of Consciousness program at the University of California at Santa Cruz. In her essay “A Cyborg Manifesto,” she argued for a socialist, feminist cyborg that challenges the singular identities and “grids of control” that work to contain women. She says that women need to become more technologically proficient and better able to engage with the “informatics of domination” and challenge these systems.

KK: That is interesting to hear about the way technology is being adopted and interpreted by the feminist agenda. How does this pieces of work fit into your overall body of work as an artist?

NK: It is a little bit of a departure, as before I was looking more at nature and technology. This work is a little more personal. Having said that, I am using three different types of AI software with this work. It is really experimental, but I am using technology to tell the story of how we can see ourselves through the collective consciousness of AI. And how we can relate each other and our environment in a more nurturing way. I am always shifting the focus of my work. Right now, I am looking at the transmutation of creatures that live on the plastic garbage patches that float in the ocean. These creatures are actually creating ecosystems within the garbage patches. This work is still connected to technology, the environment and how we use resources. There was a previous project I had worked on where I envisioned a world where only androids and creatures that could eat plastic were left thriving in a plastic world. When I read that this dreamed-up situation is actually happening in a way, that organisms are already adapting in real-world plastic habitats, I decided to explore these real-life elements in more detail.

KK: How does one access the digital images at the show at Espace L? There is a QR code, but could you describe how it works and how these pieces were created?

NK: There is an app called Artivive that you download onto your phone, and then there is a video that comes up when you point your phone at the QR code next to the image. This allows you to enter each world of the image which has a unique environment, character, story and voice.

I created all the images around the same time. I prompted a program called Midjourney to generate images, and then I chose the images that make sense with my own poetry and prose, and the emotions that I am feeling. Then I use different AI programs to make them into videos. I used Runway to make them into video and HeyGen to make them speak. None of the voices are my own, they are all cloned voices from an AI program, so everything is fully AI-generated except the texts that I wrote. I also use photoshop to edit the images, so it took about a year to create all the pieces in this show. Even though you are using tools which should make the process go more quickly, it takes time to create and edit everything.

KK: What do you think about the fact that some people do not like AI-generated artwork and think that art should be created by humans without input from AI. What would you say to them?

NK: I would like to think that this project proves that we can move forward with AI in the same way that we have accepted photography and photoshop. I have always worked in digital art and there has always been a questioning of using technological tools as a medium, but for me it has been the most natural way to express myself. There is a lot of thinking and artistry that goes into it, I don’t just push a button and it happens. I think sometimes AI-generated work, NFTs or digital art can be a certain aesthetic style that I am not very interested in. I am much more interested in the ideas and research that go behind the work. It is something personal as well as technological. I think of it as a personal collaboration with a non-human.

Nacoca Ko, Power comes from a soft place at L’effect Ferdinand exhibition at Espace L.

Use the Artivive app and point at the image to see the video.

KK: Who or what are your inspirations?

NK: Ian Chang is one inspiration. He wrote a book called “The Emissaries Guide to Worlding” and in it he looks at artists and what different personalities you can be and what roles you can take. You can be a creative, a director, a hack, or a cartoonist. It helped me understand that to create I can be many things. I can be a hack, and just understand the technology well enough to use it for what I need, and it isn’t necessary to know everything about it. It gave me permission to focus on the storytelling elements of my digital art.

Another inspiration was my uncle, the artist Bill Gersh. He was part of the counterculture in Taos, New Mexico, where he built a commune in the mountains and made houses out of adobe. He worked with assemblage and junk and used it for his art, which is a practice I follow as well.

KK: Which one of the characters you have created for the show at Espace L is your favourite?

NK: The birthing one is the first one I did, and it refers to birth as an act of creation. I often wake up in the middle of the night with a lot of creative thoughts. Women used to go out in the night and have their babies in the fields, when everything was quiet, and they had no other responsibilities. So this image really speaks to me as a woman and mother and artist, and emphasises our innate feminine strength and creativity.

Cover photo credit: Jeremy Spierer

Use the Artivive app and point at the last image to see the video.