Paintings by Chloe West are on display in At Your Altar at Galerie Mighela Shama. West is an American artist born in Cheyenne, Wyoming in 1993, now living and working in St. Louis, Missouri. West is continually inspired by European art from the Medieval and Renaissance eras and her upbringing in the American West. Her work references 17th-century Flemish and Dutch still life and vanitas paintings, as well as the Baroque tradition of the depiction of the nude figure. The artist is fascinated by the history of representation, symbolism, and functions of the gaze as it relates to the human form. The eight paintings in At Your Altar blur the line between the religious and the secular, and most were created during a seven-week residency at the gallery. In anticipation of the vernissage, Art Vista Magazine spoke with Chloe about collecting bones, shrines, the influence of the Baroque nude, and more bones.

Chloe West, Still Life (Deer Jaw), 2023. Oil on linen. 30.5 x 40.5 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Mighela Shama. Photo: Julien Gremaud

Kristen Knupp, Art Vista Magazine: Congratulations on the show at Galerie Mighela Shama, your work is stunning! I wanted to ask you about growing up in Cheyenne, Wyoming. It obviously impacts your work in terms of subject matter, and I wanted to know at what point you knew that you wanted to be an artist?

Chloe West: My parents are both artists, so I was raised around a lot of art, going to museums, and making art. When I was in high school it was a serious hobby, and I made paintings at home for fun. When it came time for college, it was the only thing I wanted to do. Even though my parents had art degrees it still seemed like kind of an odd thing to do, however, they were very supportive of my decision to study art. I was an art major at University of Wyoming, and that is how it started.

I applied to graduate school right out of undergraduate, and I was just looking to get out of Wyoming. I was recommended Washington University by professors from undergraduate, and I was really interested in the faculty. There is a painting professor called Jamie Adams who I wanted to work with there. At the time, St. Louis felt like the big city, which sounds silly now, because it isn’t a very big city. But I was coming from Laramie which is such a small town, and so it felt big and exciting. St Louis felt just right for me.

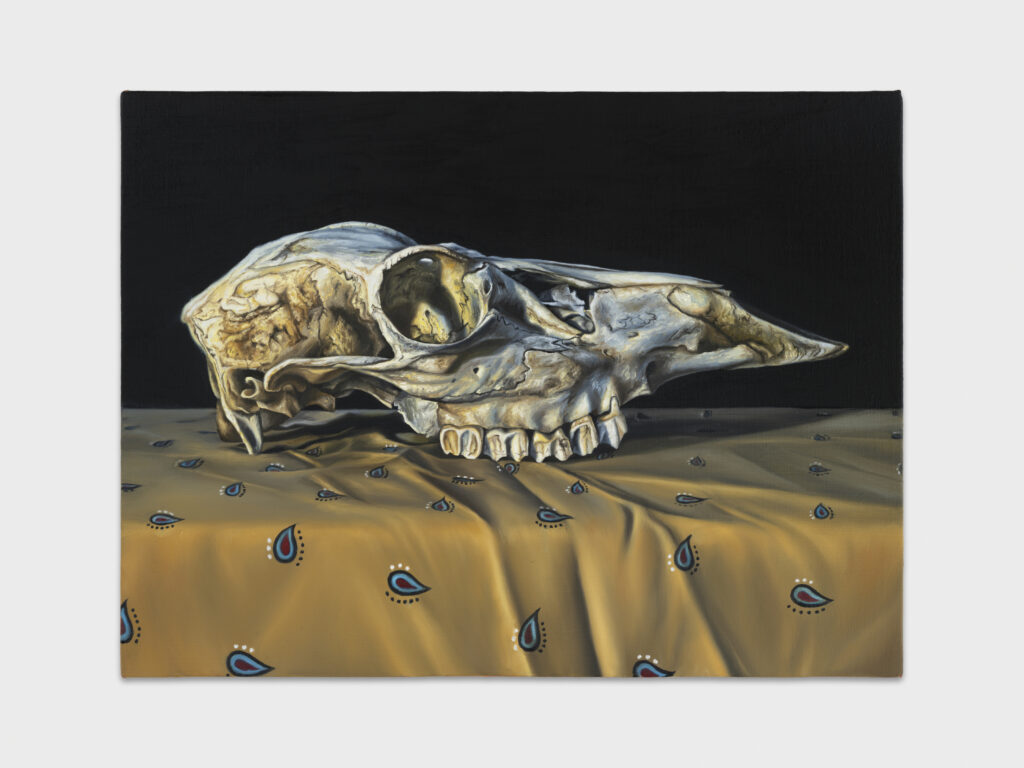

Chloe West, Still Life (Deer Skull), 2023. Oil on linen. 30.5 x 40.5 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Mighela Shama. Photo: Julien Gremaud

KK: I wanted to talk about your work being shown at Galerie Mighela Shama. There are some smaller still life paintings that I have read are inspired by Dutch vanitas paintings. Could you describe these?

CW: These are very much vanitas paintings as they reference Dutch still lifes with the tablecloth setting. The bones in the paintings are a deer skull, a cow femur, and a deer jaw. All the bones were found in Wyoming during walks that I took during the pandemic. Some of the paintings I started at home and finished in Geneva. The three small still lifes hang alongside a portrait of Mother Cabrini. She is the saint on display at the Saint Frances Cabrini shrine in New York City and I have visited her a few times with my dad. She is in a glass coffin and she was sainted because her body is incorruptible, which means it is not supposed to decay after death.

There is actually a wax mask that is placed over her face because she did decay, of course. They don’t tell you it is a wax mask because you can’t get too close, but I found out researching it online. I grew up going to shrines and religious sites because I find them to be super interesting, although it is a slightly strange pastime. At some shrines there are little reliquaries inside something like a ring box, and it could be a splinter of wood that is supposed to be from the original cross. Sometimes it is not clear whether they are really old or not. They are big inspirations for me in my work.

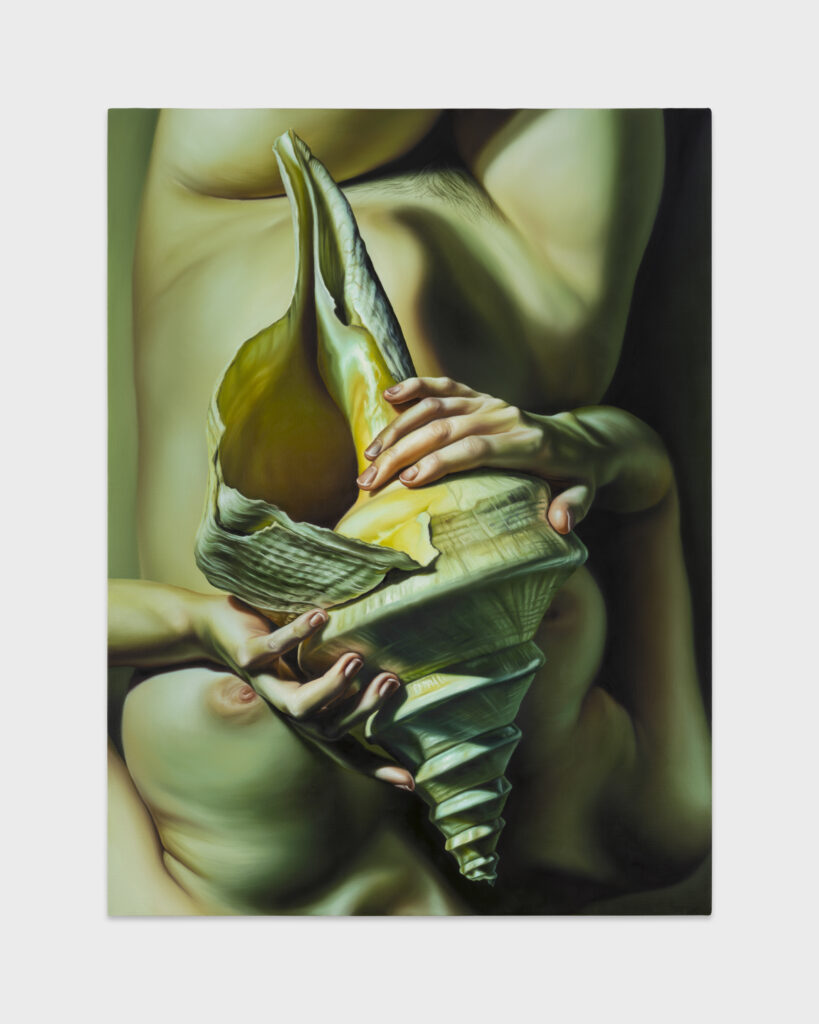

Chloe West, Shell, 2023. Oil on linen. 81 x 61 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Mighela Shama. Photo: Julien Gremaud

KK: Another painting in the show depicts a large shell and the lighting is quite Baroque; chiaroscuro with a greenish tinge. Could you tell us about this painting?

CW: I love Baroque paintings as well as medieval and Renaissance paintings, they are a strong inspiration for my work. The greenish tinge is invented. I invent the colour palette throughout the process of making a painting. The green tone has been in a lot of my work. I started doing them because I was looking at paintings from the Medieval and Renaissance eras that have green bodies, such as a depiction of a green Jesus, or bodies that are not even meant to be dead necessarily. I became fascinated with that colour palette. Not all of the bodies in these old paintings were painted green. In some of them, they used a traditional technique of layering paintings with an underpaint in green and then glazed red tones on top to look like naturalistic skin tones. Over time, the red pigments were fugitive, and they faded, so only the green tones were left.

I became obsessed with that and researched paintings to find out if the green was intended or if it was because of the erosion of time. There are many paintings of Jesus where he is on the cross or deposed from the cross where he is very green, which is meant to signify death. I love to track history and find out what techniques and materials artists were using in the past. I feel very connected to the Renaissance era which is considered to be the height of oil painting in Europe.

Chloe West, Shell, 2023 (detail). Oil on linen. 81 x 61 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Mighela Shama. Photo: Julien Gremaud

KK: Could you talk about the technique you used to create these paintings? I imagine they take quite a long time to paint because of the detail and precision of these pieces.

CW: I start with a traditional Flemish or Venetian technique. They are on linen and are gessoed. Then I start with an imprimatura, which is a flat layer of colour. Some of these paintings would have started green, the larger paintings started as burnt sienna. The first layer is the full image that gets established. I paint a partial grisaille, which is a monochromatic layer, or a brunaille, a brown and white layer, and then I add full colour. And more colour and more colour until it is done. It takes me about a month to create each painting, working every single day. I could work on them forever. The residency at Galerie Mighela Shama has helped me to shorten my timeline since I can be very concentrated. The scale of a piece is determined by the image. I love painting on an intimate scale, such as in the still lifes. The scale of the bodies is a little larger than full scale in order to create more of a presence in the painting.

KK: I read that you went on long walks in Wyoming during the pandemic, during which you would pick up bones found along the way. Is that when you first started to use bones in your work?

CW: Yes, I didn’t start the body of work with the bones from Wyoming until three or four years ago when I had time to process what it meant to go back home and make work connected to where I am from. I feel very connected to the land there. It is part of who I am and my family is there. During the pandemic, I became obsessed with finding and collecting bones, and then painting them. We went out hiking every day, all day, to places that were very isolated. No one else was there except perhaps hunters. Now my parent’s entire backyard is filled with bones.

Chloe West, Still Life (Cow Femur), 2023. Oil on linen. 30.5 x 40.5 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Mighela Shama. Photo: Julien Gremaud

KK: Is the symbolism of bones in your work meant to be connected to mortality and the cycle of life?

CW: Of course, that is definitely a part of it. You can’t escape that symbolism. But I also find them to be so beautiful and powerful as objects. Beyond thinking about death, I think equally of life. They are so symbolic of where I am from and are a big part of Western culture. It is a common practice to keep trophies from hunts. The bones I have found are ones that people did not keep because they are not the prize bones. A leg bone is not as coveted as a big rack of antlers. But I love them so much, they are so precious to me. When I take the photographs of myself in Wyoming with the bones at the start of the creative journey, it is an intuitive process as to how I want them to relate to my body. Often they mimic my own anatomy, and I feel that I want to hold them close to the center of my body. It is mostly just instinct.

KK: Are there any contemporary artists that you look to for inspiration or are you totally focussed on the past?

CW: Personally, I tend to go a little inward when I am making works, so I try not to be too affected by what is happening in the contemporary art world around me. I don’t know if that sounds odd. There are artists that I love, but I am primarily inspired by Old Master paintings because I feel so connected to that history.

Chloe West, At Your Altar is at Galerie Mighela Shama until December 1, 2023, with an opening night conversation between Chloe West and Malka Gouzer on October 5th at 7 p.m.

Cover image portrait photo: Brea Youngblood