The contemporary African art market is booming. According to Pavillon 54, 2022 saw a record number of works by African artists sold at auction (more than 2,700), almost twice as many as before the Covid pandemic. Last year, works by Contemporary artists born in Africa generated $63 million at auction versus a previous record of $47 million in 2021. In Geneva, there are four galleries presenting contemporary African art: Filafriques, Gallery Brulhart, iLAB-Design and Les Arts du Soleil. Co-existing alongside these galleries are many artists from the African diaspora, particularly French-speaking countries. In addition, the historic context of African art can be found inside the walls of the Musée Barbier-Mueller, while further afield in Lausanne, Foreign Agent gallery specialises in African art and design. Why have these contemporary African art galleries chosen to be located in the Suisse Romande and what is the future of contemporary African art in Geneva and beyond? One can look towards the influence of the international community and the African diaspora, drawn here by institutions like HEAD, the Geneva art school, as well as the inspiration from contemporary African art fairs such as the Dak’art Biennale, AKAA Art and Design Fair and 1-54, for answers.

Adeogun Babatunde, Black Lives Matter, Oil on canvas. Courtesy of ILAB Gallery and the artist.

The international draw of Geneva contributed to the creation of one of the first galleries specialising in African art in Geneva: iLAB-Design. Founded in 2018 by Besigin Tonwe-Gold and Véronique N’Daw Dunoyer, the gallery presents a selection of artists and creators spotted during the founder’s visits to Africa. Tonwe-Gold arrived in Geneva via Nigeria thanks to parents in the diplomatic corps while Véronique N’Daw Dunoyer is French, of Senegalese origin, and has been living in Geneva for 25 years. The market has developed since they established the gallery. However, in comparison to other larger cities with concentrations of contemporary African art galleries, such as London, Paris and New York, Tonwe-Gold says, “Geneva is still at an early stage with a few specialized galeries in contemporary African art and, accordingly, relatively few transactions”.

The founders of iLAB make it a point to meet the artists in their environments and to create a cordial relationship, based on respect and trust. One artist represented by Ilab is Momar Seck, a Senegalese artist who has lived and worked in Geneva for many years. Seck’s involvement with Geneva can be traced back to his graduate studies in art. He was selected for the Dakar Biennale in 1992, and then was awarded a scholarship from the Swiss Federal Office of Culture to do his graduate studies at HEAD, the Geneva art school. Having spent the last year teaching and painting in Dakar, in Seck’s view, “whoever sells African art outside of Africa needs to understand the values and ideas behind the art. There is a whole culture behind the art, and galleries selling African art need to understand and promote these values.” Of course, all the participants in the contemporary African art market, whether they are curators, collectors, institutions, or galleries, should make an effort to be educated about the culture and values integral to the art. These values vary greatly from one country or region to another.

Momar Seck, Collection: United Colors of Africa: Environment 11, 2021. Mixed technique on canvas.

Furthermore, some participants in the market question whether it is appropriate to categorise art coming from Africa as specifically “African”, given the scale and diversity of the fifty-four countries on the continent. What exactly does this mean, and do we make this type of categorisation with art from any other continent, to the same extent? One gallerist questioning this concept is Madina Ba, founder of Les Arts du Soleil, with locations in Carouge and Dakar. Ba says, “I don’t really see the gallery as one that shows African contemporary art. I see it more as a gallery of contemporary art because I don’t know what it really means to say “African contemporary art”. I think that there are contemporary artists period, full stop.”

This sentiment has been echoed by others in the artistic community including Victoria Mann, founder of AKAA art fair. Echoing the sentiments of Madina Ba, the name AKAA (Also Known As Africa) reflects a reluctance by Mann to restrict the fair or exclude artists based purely on location. As she states: “I did not want to create a fair that cornered artists into a box that is contoured by the borders of a continent. The idea of geography was obsolete for me because an artist should not be identified as good or not good because of where he is from. They should be identified a good artist because of what he does. Labelling artists African when we don’t really do that with the rest of the art community and the art world did not feel appropriate.” In other words, the sources of culture, history and identity coming from the African continent are immense and it is difficult to contain them in just one word. Mann continued, “the criteria to be at the fair is not to be African but to claim a link to Africa in your work.” As part of the selection process, AKAA asks every artist to tell them about their links to, and definition of, Africa that comes out in their work.

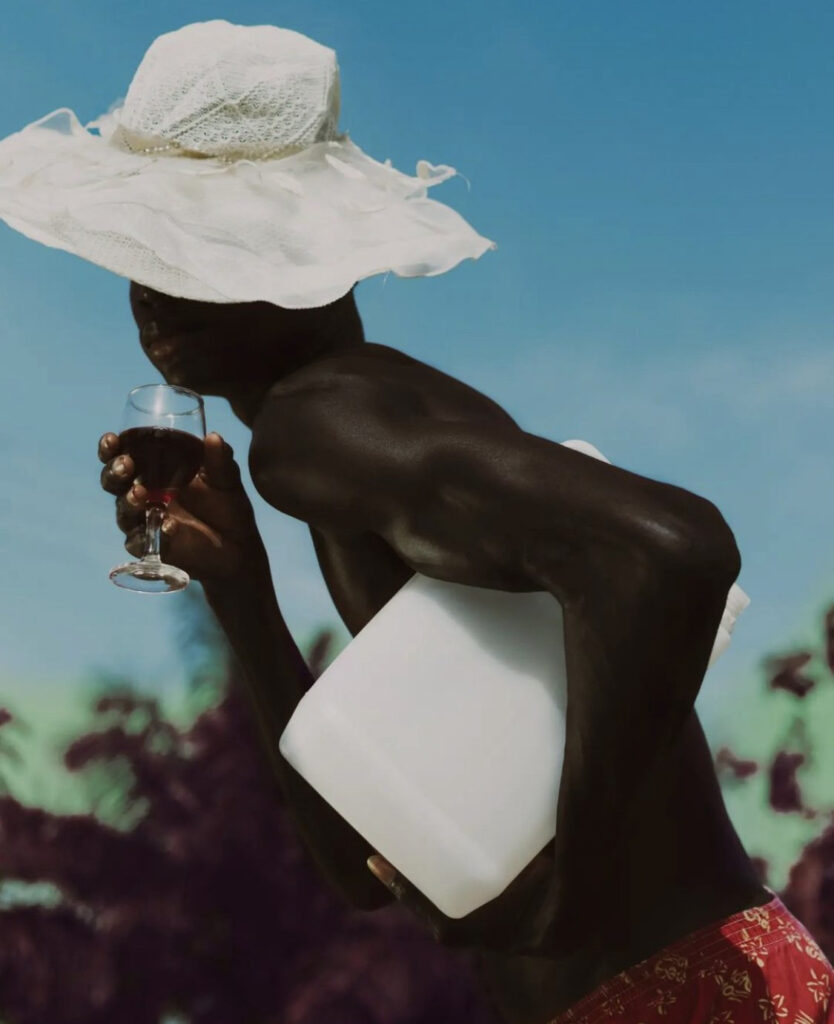

Roasted Kweku, Test a bit of your thinking, photograph. Courtesy of Filafriques.

The influence of art fairs like AKAA on the growth of the contemporary African art market can not be overstated. Carine Biley, founder of Filafriques, spent time at art fairs prior to starting her gallery. She says: “At AKAA, in particular, I felt like I really belonged, and it was obvious, I felt at home and the contemporary African art scene was calling me.” Biley’s focus for Filafriques is to show the diversity of art from Africa. Her first exhibitions were in a gallery space in Geneva near Cornavin, where she featured work by Roasted Kweku from Ghana, Sisqo Ndombe from Kinshasa, and Gavin Goodman from South Africa. Biley has since added more artists to the gallery roster during her travels to Africa. In addition, during the pandemic, she shifted gears and now exhibits her artist’s work at collaborative spaces such as the Mövenpick hotel, Qafé Guidoline and the Global Health Campus close to the U.N.

Exhibition view at Gallery Brulhart: Dr Gindi, She that spreads the Winds, bronze, 2021 with barkcloth work by Sheila Nakitende.

The international community of Geneva contributed to the start-up of several other galleries specialising in contemporary African art. Prior to founding Gallery Brulhart, Mona Brulhart worked at the United Nations Refugee Agency in sub-Saharan Africa. The gallery is focused on presenting work by women artists of African heritage because “women artists, and African contemporary artists have been historically underrepresented in the art world.” A recent exhibition combined the work of Dr. Gindi, a sculptor with Egyptian roots, with the barkcloth tapestries of Sheila Nakitende, an artist from Uganda. Beyond Geneva, Foreign Agent in Lausanne was founded by Olivier Chow in 2019. Chow’s work for the ICRC enabled him to work and travel in Africa where he developed a strong interest in African art and design. In his view, the contemporary African art market in Suisse Romande “is still a small scene but it is connected to other places around the world which makes it quite dynamic.”

Maurice Mboa, Bonam, 2021. Acrylic on engraved aluminium sheet. Courtesy of Foreign Agent and the artist.

This connection to other parts of the world means that many artists with connections to Africa, too many to mention all of them, live and work in Geneva. During a recent contemporary African art parcours, organized by Charlotte Diez-Bento, founder of This is your Heart art advisory, and Christine Cibert, we visited several artists’ ateliers. The purpose of the parcours, which was the first of its kind to be organized in Geneva, was to demystify the contemporary African art scene with visits to artists’ studios, talks with collectors, and links to cultural programming in the Suisse Romande. During the parcours, we made a stop at the atelier of Gilles Dusabe. Dusabe has Swiss, French and Rwandan citizenship and lives and works in Geneva. He has had a peripatetic journey through the art world, attending art school and working in several countries. The impact in particular of participating in the Dak’art Biennale 2022 was especially noteworthy for Dusabe. He was “stunned by the level of the artists. The ambition was amazing. There were huge installations. I think the fact that there were these monumental pieces was quite impressive.”

Gilles Dusabe, Rainbow Skin installation. Photo: Christel Arras

The art parcours culminated with a visit to Omar Ba’s studio. Omar Ba, a Senegalese artist born in 1977, lives and works between Dakar and Geneva and is represented by the Wilde Gallery in Switzerland. He originally studied at the Ecole National des Beaux-arts in Dakar and, like many of the artists from the African diaspora, came to study at HEAD in Geneva. His mixed-media paintings are both figurative and decorative, with symbolic elements, and he often paints on pieces of cardboard as well as cardboard boxes. Upon our visit, his studio was filled with several large-scale paintings in various stages of completion, as well as stacks of black-painted cardboard boxes. Arguably one of the most well-known artists from the diaspora, Ba’s career path has inspired many to try to emulate his success.

Omar Ba, Shadow 1, 2021. Oil, acrylic, Chinese ink on cardboard. Courtesy Wilde Gallery and the artist.

Beyond the galleries and artist ateliers, institutions in Geneva contribute to the depth and breadth of information available about African art and culture. In celebration of the museum’s 45th anniversary, the Musée Barbier-Mueller is exhibiting the work of contemporary sculptor Arik Levy and painter / sculptor / engraver Zoé Ouvrier in dialogue with its permanent collection of African art. It has also been announced that the Musée d’ethnographie de Geneve (MEG) will present Afrosonica – Soundscapes in May 2025. This will be an exhibition to discover ancient and current musical traditions of the African continent, with interventions by conceptual artists commented on by South African curator, artist, and composer Mo Laudi (Ntshepe Tsekere Bopape) and Madeleine Leclair, curator of the Department of Ethnomusicology since 2012. Beyond the institutions, there are serious contemporary African art collectors with links to Geneva, including David Brolliet, among others. Among this cultural richness, additional exhibitions with an African focus are undoubtedly on the horizon in Geneva.

Leuna Njiele Noumbimboo (Bimboo), Crossed Looks, 2022, courtesy of Les Arts du Soleil.

With all the cultural offerings and focus on contemporary African art, is it still considered to be an emerging art market? Victoria Mann states: “Ten years ago…we were talking about an emergent art market, not emergent art scene, because the artists have always been around…today, I don’t think we can talk about the emergent art market.” In the last few years, most large galleries have added artists from Africa to their artist list, while the major institutions have acquired work from Africa and its diaspora.

Where will the contemporary African art market go from here? In order to make the market more sustainable, Madina Ba of Les Arts du Soleil would like to see the local African market grow to accommodate all the artistic talent and art available. She says: “I think more Africans need to buy African art to make sure that the market remains solid and definitive. If not, there is an enormous amount of talent that will emerge but some won’t get the attention they need to succeed.” In the Geneva area, the galleries focused in the this market seem to be in a perfect position to capitalise on the recent focus on contemporary African art in the larger art world, and to continue to educate collectors about art from Africa and its diaspora.

Cover image: Gavin Goodman photograph, Filafriques.