Facing hardship, upheaval, loss, we are often confronted head-on with the starkest aspects of the human condition. Brought to the forefront as the pandemic follows its unruly course, wreaking havoc in its wake, these relentless ordeals persistently plague (no pun intended) our quotidian. Picking up where my last discussion left off—how art can mediate our quest for meaning amidst the paradoxes and inevitable mysteries of life, paramount among them being death—I delve further into these ongoing concerns in my series “Fluidity of Being,” the focal point of this column, in which I ponder the interconnectedness of art and experience across time and geography.

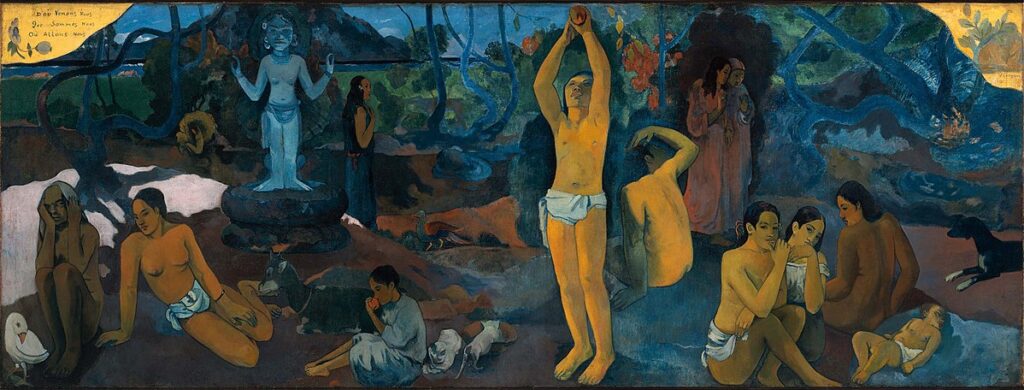

Paul Gauguin, Where do we come from, what are we, where are we going? 1897-1898, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Painted during a time of deep personal distress, Paul Gauguin’s monumental canvas Where do we come from, what are we, where are we going?, pointedly attests to the French artist’s search for answers to these timeless questions. He traveled to Tahiti, at the furthest reaches of late-nineteenth-century French territory, seeking a fantasized return to an imagined original state. Within mere decades, scientific and technological advances expanded the scope of discovery exponentially to the limitless domain of outer space. And artists followed suit, adapting their means of expression to visualize the invisible. Probing the unknown, science seeks to unlock the hidden secrets of the universe, whereas art forges a path to plumb its fathomless depths, seizing upon its chaos and incommensurability to reveal other dimensions of the worlds we inhabit. Often viewed as diametrically opposed, art and science nonetheless intersect in myriad complementary ways, especially in gauging the ontological shifts in the nature of reality heralded by early twentieth-century scientific breakthroughs. From Einstein’s theory of relativity to quantum physics, these debates rage to this day, and in turn, continue to inflect the arts.

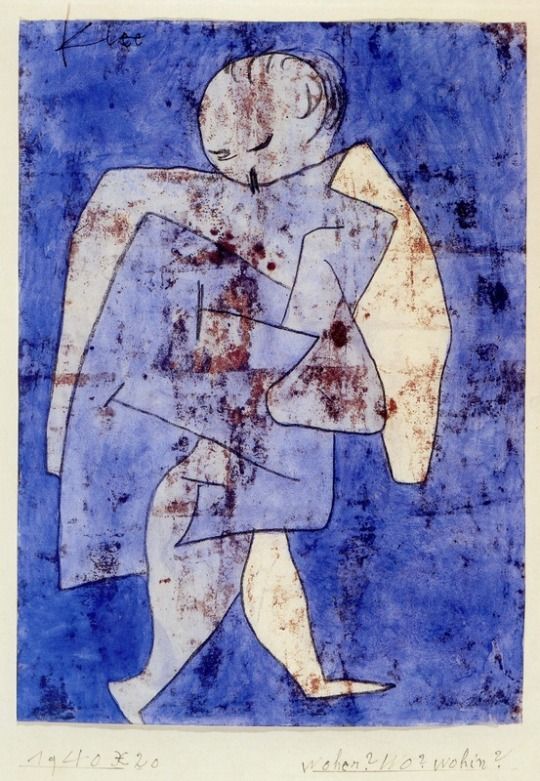

Paul Klee, Whence? Where? Whither? 1940.

In 1940, during the last year of his life when he was faced with a debilitating illness, Paul Klee produced Whence? Where? Whither?, a late iteration of the myriad angels populating the Swiss artist’s oeuvre. Echoing the title of Gauguin’s magnus opus, Klee’s diminutive, intimate work likewise queries the enigma of existence and gestures to our passage through the infinity surrounding us. In exploring the limitless potential of the imagination, Klee sought to capture the dynamic conception of the cosmos beyond the observable world that had recently been theorized by the leading scientists of his time. He famously stated that the purpose of art was to “make visible” rather than “reproduce the visible.” For Klee, the work of art originates from “a secret spark… which kindles the spirit of man with its glow and moves his hand…and the movement is translated into matter.”

Paul Klee, Angelus Novus, 1920.

Yet Klee’s angels, beginning with his renowned Angelus Novus, embody our movement—between terrestrial and celestial realms, from one dimension to another, through the immensity of time and space. Dubbed the “Angel of History” by German philosopher Walter Benjamin, who acquired and coveted it for nearly two decades until his untimely death by suicide— the foreboding hybrid being floats with wings outstretched in the nebulous space of the paper support, suspended in a space-time void. Hovering between the past and the future, the figure glances sideways, perhaps backwards, hinting at the engulfing immensity. Both heavenly and all too human, the angels invoke the artist’s preoccupation with the soul.

Dr Gindi, Flying into Life (detail), Bronze. 2021.

Though formally and materially quite distinct from Klee’s oeuvre, my sculptural practice shares many similar concerns, both conceptual in nature and approach. The recent bronze sculpture Flying into Life—part of the same “Fluidity of Being” series as The Last Second, which featured in my October column—embodies the process of discovery and transformation, of channeling individual energy to reconnect with the dynamism of the infinite cosmos. The roughly molded figure, with limbs splayed and held aloft by intersecting rods akin to luminous rays of cosmic light, seeks to convey a certain tension, as if the body were also flailing in free fall. The sculpture captures the levity of the soul taking flight but also the work of art emerging from the act of creation. Taking its cue from the paradox inherent in all existence, the push and pull of seemingly conflicting dichotomies and oppositional forces, my work attempts to orchestrate a precarious balance, that of the physical body in thrall to inner nature, reaching out to achieve universal infinity. To borrow again from Klee’s own words:“One deserts the realm of the here and now to transfer one’s activity into a realm of the yonder where total affirmation is possible.”

To find out more about Dr Gindi’s work, please go to www.dr-gindi.com or @gindisculptor