Kristen Knupp of Art Vista Magazine met with Leo Villareal at Pace Gallery, Geneva, on the eve of the opening of his show Nebulae and during the week of artgenève, which will feature a special presentation of a work by Villareal, Optical Machine 1. Leo Villareal is an American artist who works with pixels, LEDs, and binary code to create complex compositions of light. Villareal is perhaps best known for The Bay Lights project in which he installed 25,000 LEDs on the San Francisco Bay Bridge that create mesmerising patterns, or for the Illuminated River project in London where 9 bridges over the Thames are lit in innovative compositions that respond to the individual character of each bridge. Here, Villareal talks about getting inspiration from the cosmos, how he defines himself, the importance of connecting, and the attraction of anonymity.

‘Leo Villareal: Nebulae’ installed at Pace Geneva, Geneva, January 24, 2023. Name of photographer: Annik Wetter © Leo Villareal, courtesy Pace Gallery

Kristen Knupp: I have read about your Burning Man moment, which is a fantastic story about how you created a remote-controlled light sculpture in order to find your way back to your camper, and this kicked off your interest in combining technology with sculpture. I wanted to ask you about before that, what made you want to become an artist?

Leo Villareal: Well it took me a while. I was at Yale as an undergraduate, and I did a lot of set design when I was first there and I studied art history. Then I took my first installation sculpture class and realized that I really wanted to be an artist. I fell in love with it. At Yale, I was with Matthew Barney and Sarah Sze and some amazing graduate students, so I felt very lucky to be a part of that. I had always also been interested in technology but wasn’t quite sure how I would use that creatively.

When I finished Yale in 1990, it was the year when Photoshop first came out, and suddenly you could do something amazing and edit images on the computer which I found mind-blowing. There was also buzz about virtual reality, the first time around, which really got my attention. It was very expensive and difficult to get access to these technologies so I went to the NYU Interactive Telecommunications Program where they had all these machines and million-dollar supercomputers that I could use, not really knowing what I wanted to do. There was no industry around this except making CD ROMs for no money. It was two amazing years at NYU immersing myself in all kinds of technology.

Then I got an internship in Palo Alto in 1994 at Interval Research which Paul Allen had started. It was amazing to be in Silicon Valley which was the Mecca of technology and I was very excited to be out there. It was a utopian place at that time, with engineers, programmers, musicians, designers, and artists, so it was inspiring to be there. That was the same summer I went out to Burning Man and had that moment with light and software and space. It all coalesced, and I feel very lucky that I had the time to figure it out. Eventually, I started my studio in New York in 1998, and then I had my first solo show in 2002. So it all happened at a leisurely pace, compared to how things seem to work these days.

KK: I read that you exhibited a piece alongside a work made by a CERN collaboration. Could you tell me about that?

LV: I made my first public artwork in 2003 at MoMA PS1, where I displayed a piece called Supercluster on the outside of the building. CERN was there as well with an exhibition called Signatures of the Invisible (a collaboration between the London Institute and CERN that presented work made by contemporary artists together with physicists). I felt very lucky to be a part of that group. I have always been very intrigued by CERN and its work.

‘Leo Villareal: Nebulae’ installed at Pace Geneva, Geneva, January 24, 2023. Name of photographer: Annik Wetter © Leo Villareal, courtesy Pace Gallery

KK: The Nebulae exhibition at Pace is colorful, with glowing ever-changing pieces hung on the wall like paintings. Could you describe the process of making the pieces: how long does it take, how many people work on them?

LV: Nebulae is a series and I have been making these pieces for just over a year. It is a grid of color LEDs that are diffused with a piece of acrylic which softens all the colors. There are 16 million colors with each LED so it is a very rich palette. I work with many fabricators and engineers to make it as seamless as it is. There are of course computers and wires, but I like to focus on the visual manifestation of the code.

KK: What is the starting point for the Nebulae series?

LV: I think it is the idea of understanding the phenomena that surround us. I am very interested in nature and trying to understand it. My work is different from a photographer or a painter recording nature because I am using code and creating these things from the ground up using software of my own making. That has been interesting to me, to use simple things to create much larger expressions of vastness, the cosmos. There is also the ever-changing nature of the pieces, they are not static and are all about time. So this is interesting to present in Geneva, in a place that is so obsessed with time. I have been looking at them in a different way after I have been in Geneva for a week. I have been thinking about the timing of celestial mechanisms and the unknown. You can’t help but try to find patterns in these pieces, that is the way our brains work and we are always trying to find a pattern and decode things. These pieces are abstract and will never resolve into an image and will always shift into something else, so there is a slippery quality to them.

KK: I saw James Turrell’s work here at Pace Gallery, Geneva, and this exhibition reminds me a little of his work which displays a very slow change of color over time. Is he one of the artists that inspire you?

LV: Turrell is amazing. I’m inspired by Turrell and Flavin. I bring computation to the light work that they do which I think is a little bit different to what they are doing. The code is very important to me. It is the essence of the work. It is amazing what you can do with it. Breaking down really complicated things into a piece of code. So for the last year, I have been working in generative art. I presented a few NFTs and the idea is to make a small amount of code and when you run it creates a unique output. Those works are being traded online and don’t have a physical component.

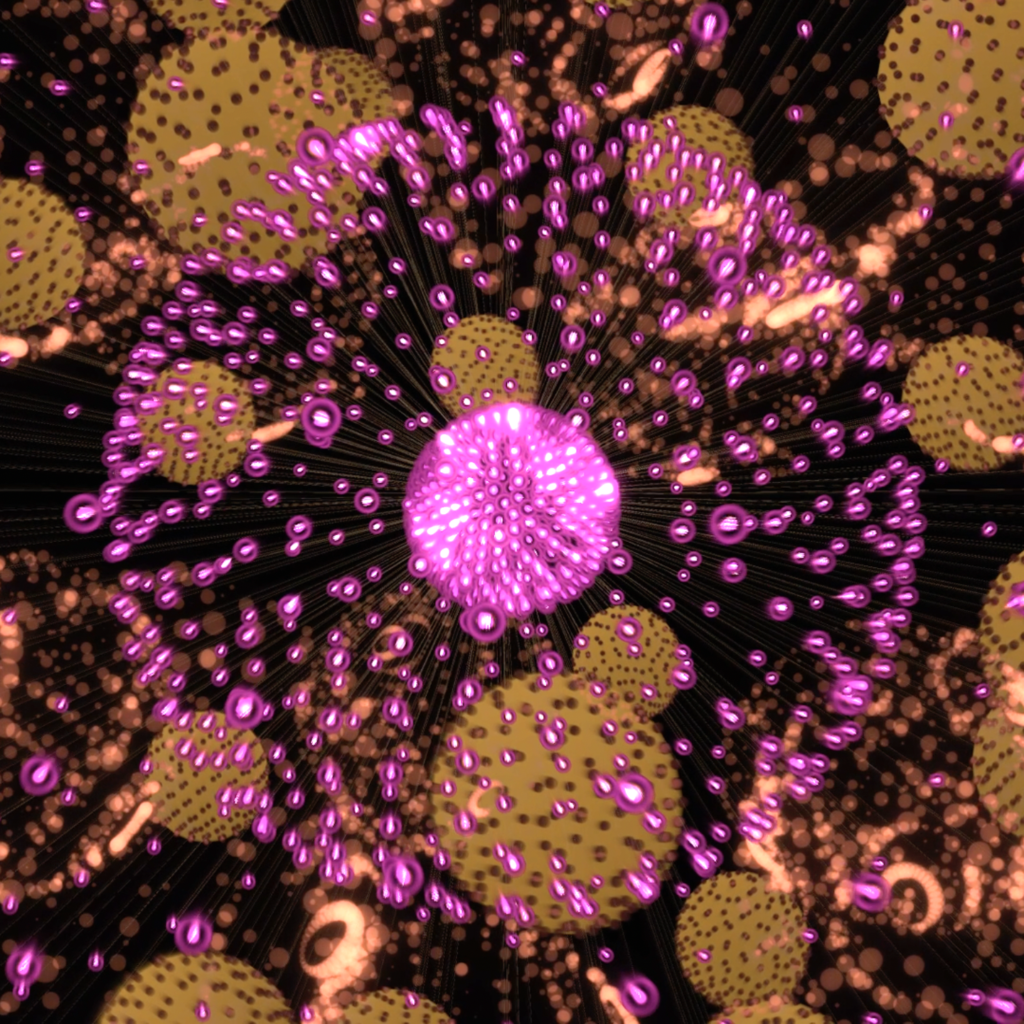

‘Leo Villareal: Cosmic Bloom Sample Output. © Leo Villareal, courtesy Pace Gallery

KK: You have created the NFTs Cosmic Reef and more recently, Cosmic Bloom which was released in December 2022. What does someone get when they buy one of your NFTs?

LV: They buy a token that represents a unique iteration of the code. At the time of minting, it is what is called a blind mint, and the buyer does not know what the output will look like until they buy it. This is what happens in the primary market. Then there is the secondary market where a lot of trading occurs and you can buy the output that you want. NFTs are very interesting. Initially, I could not wrap my head around it, but over time I have found them to be compelling. A lot of the work I did to create Cosmic Reef and Cosmic Bloom helped to feed into the work shown now at Pace.

KK: In your opinion, what is the future of technology in the art world?

LV: I am very excited when artists use technology and there are so many things you can do living in this golden age and being able to manipulate images and light and sound. However, I really don’t like being called a tech artist or media artist, I just want to be an artist. I just happen to use technology. I think it is connected to things artists have been thinking about forever; how do you capture the way you see something and transmit that to someone else? I think that is a very old idea. I am all for more people using technology. There is a level of speculation in the NFT space and some of it is not that interesting. But at its core, I have found amazing people doing great work and I have been lucky to work in that space and trade purely digital work which I never could do before. I do have to give up a little control over how my work appears physically, whether it is on someone’s phone or a low-resolution monitor, etc. On the other hand, it is exciting to know that more people can have access to the work. The crypto audience is very different from the art world audience. NFTs are similar to public art in that it is a way to connect with more people and embrace new technology. I think in the future people will be more discerning in the NFT market.

KK: I wanted to ask you about the Illuminated River project in London for which you entered and won a design competition. This reminds me of what architects do when they compete for projects and I wonder if you feel like an architect, a sculptor, or a computer tech person? How do you define yourself?

LV: I love my team and we have an amazing studio in Brooklyn with ten people, and more available as needed. We work to create light sculptures that are for sale through Pace Gallery and to realize commissions of all scales, from smaller work for people’s homes, to larger activations for building facades and interiors, to monumental public works, like The Bay Lights and Illuminated River. Our clients are individuals, institutions, corporations, and civic bodies. The larger scale works realized upon infrastructure are very challenging and it is not for everyone. It requires tremendous patience, openness, and endurance to make them happen. In the end, however, you get to work on things like putting 25,000 LEDs along 1.8 miles of the Bay Bridge, so I find it to be thrilling. We have been very lucky to get these commissions. We are trying to find a balance and be careful about what we do. Someone asked me if I would retire at age 65 and I said, “Absolutely not, I love what I do.” I would like to continue doing this forever, but I will be more selective going forward. It should be a fulfilling experience, working in the most compelling sites with people we like to work with.

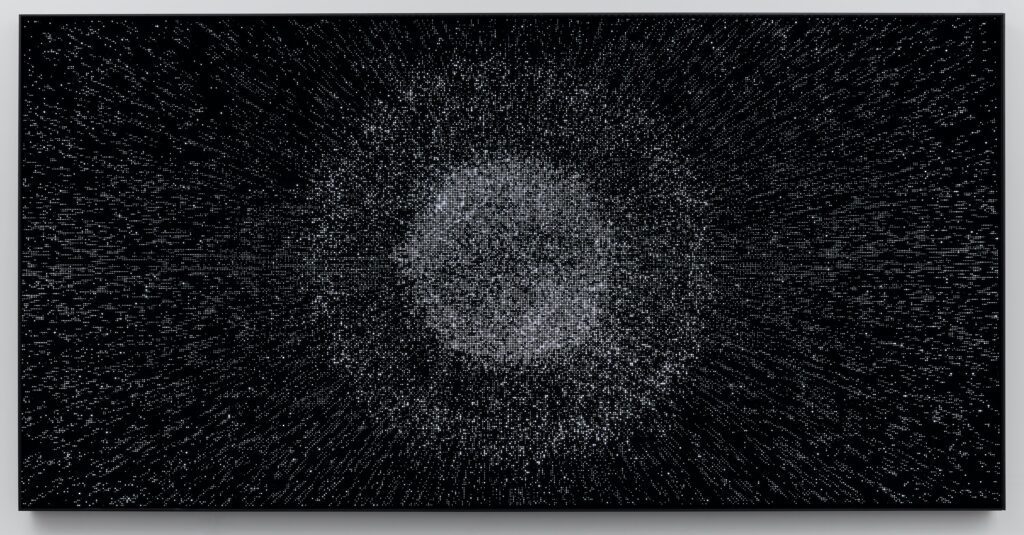

Leo Villareal, Optical Machine I, 2019, © Leo Villareal, courtesy Pace Gallery

KK: You have a special installation at artgenève, the Geneva art fair, which starts this week. Can describe it?

LV: It is called Optical Machine 1, and it is a monochromatic work using white LEDs, so it is grayscale. I was always obsessed with and inspired by Marcel Duchamp and his Rotoreliefs and Optical Machines that he would create, both of which engage with chance. It is very different from the Nebulae pieces at Pace in that it isn’t using any color, but it will be a nice contrast. Like Nebula, it has a celestial quality and kind of nano aspect. It uses the same techniques and non-repeating patterns and invokes energy and tries to capture things that are invisible.

KK: Have you done any artwork that is not connected to technology or would you?

LV: Sometimes I just want to run screaming from all this stuff and take up watercolors! No, actually, I am a very digital person. It feels like there is a wide open space to work in, a bit like the Wild West. There is so much happening in this space, you have NFTs, and immersive experiences, and there is a lot of room for creativity. There is also Virtual Reality, which we use when we are creating concept visualizations of future artworks, however, there is not really a way to distribute that experience at present. I feel like VR is waiting for the iPod moment, which was when things crystallized and we understood that music would be digital from then on. Once there is that ability to connect, then that will be another opportunity.

‘Leo Villareal: Nebulae’ installed at Pace Geneva, Geneva, January 24, 2023. Name of photographer: Annik Wetter © Leo Villareal, courtesy Pace Gallery

KK: What was your favorite project that you have done so far?

LV: It is hard to say because each one is so unique. Obviously, The Bay Lights and Illuminated River projects have been amazing to realize and to connect with so many people. The more intimate experiences are valuable as well, such as this one in Geneva. Having a range of experiences is great and at the core, it is about connecting.

KK: Will you go back to Burning Man?

LV: I’ve been going every year since 1994, apart from during the pandemic when we couldn’t go. I’ve joined the Board of The Burning Man Project and work with the founders. It is a really amazing and inspiring place. What is interesting is that the principles of Burning Man are guiding thousands of regional events happening around the world that, while they may not be on the same scale as Burning Man, are very different from the day-to-day. As much as I love what I do, I like being in a place where the rules are different and there is anonymity to it. It helps me get out of my own head.

For more information about Leo Villareal’s Nebulae exhibition at Pace Gallery click here.