KK: How did your shows in Switzerland come about?

PN: The Musee des Beaux-Arts La Chaux-de-Fonds has a new director, David Lemaire. He had previously worked at MAMCO and saw my show there (2001). Apparently, and I might have this wrong, but at his interview David said that as new director one of the first things he would do is set up a Paul Noble show! David got the job and I was his debut show. The main spaces at the Musee are both grand and modern and suited my work very well. Gagosian Geneva is a much more domestic setting so doing a show there was a good opportunity to test the works in both kinds of spaces. Their current show at the Musee is an exhibition of Konrad Klapheck’s work that I would really like to see.

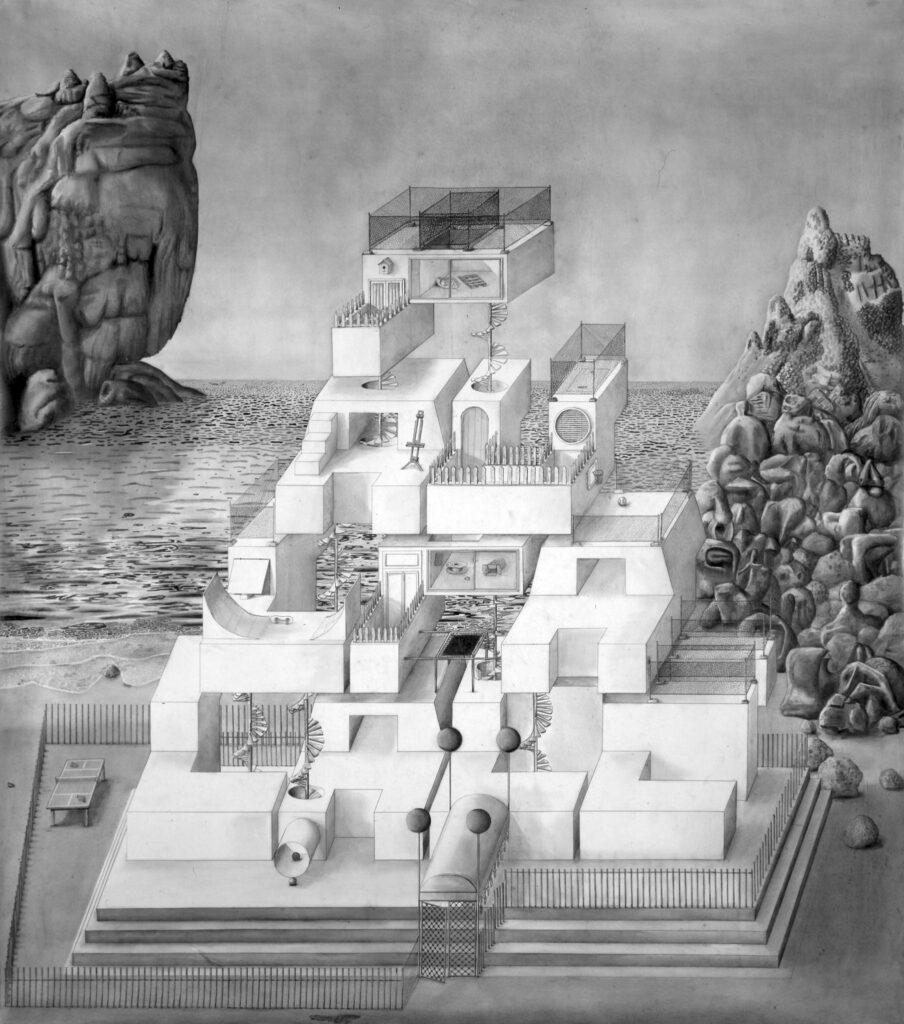

242 x 252 cm © Paul Noble. Courtesy the artist and Gagosian. Photo: Mike Bruce

KK: You have referred to the precisely-drawn world you have created, Nobson Newtown, as “an exercise in self-portraiture via town-planning” What do you see of yourself in Nobson, and how does it relate to you personally?

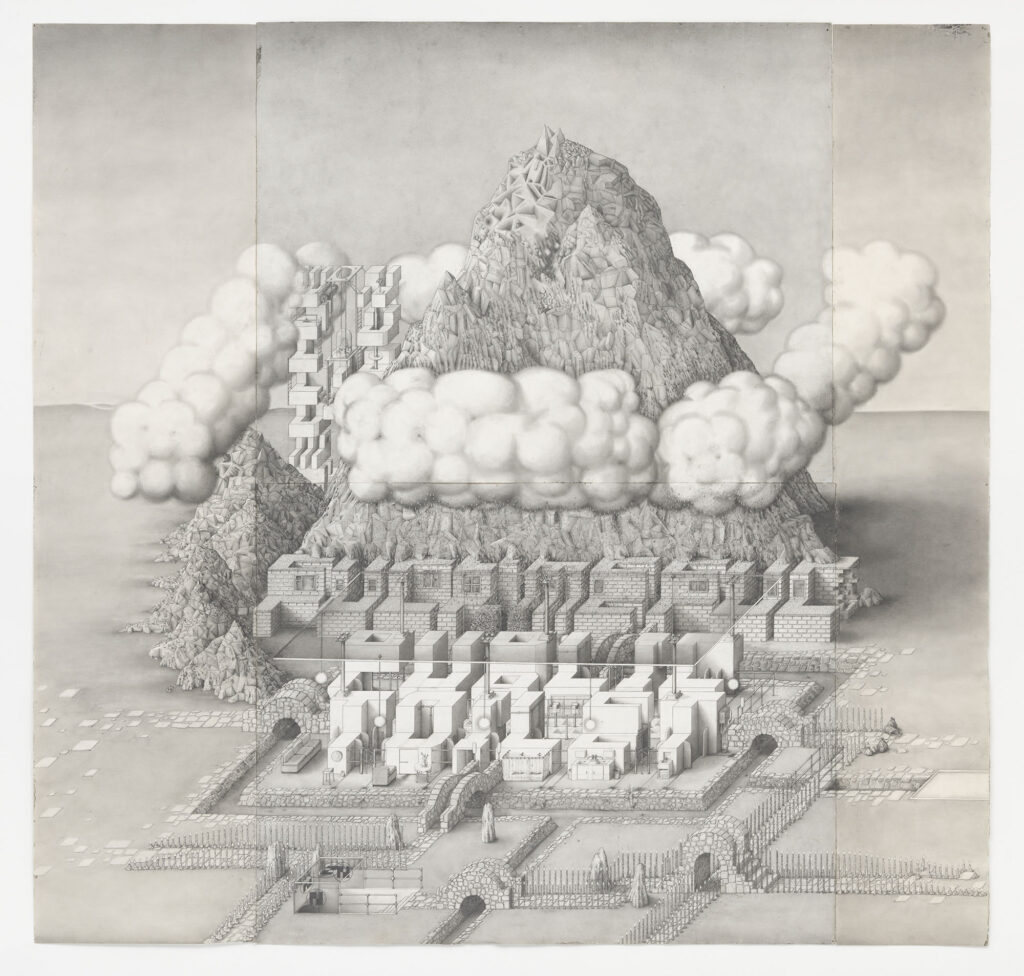

PN: I’m not really sure that I said that, it was probably someone else. Nobson is my name turned into a place. The town is me. The pictures of Nobson depict all the places imagined necessary to make ‘a town’. All of these places are seen in the same moment, 10.45 am. Before Nobson’s ‘Big Bang’ moment, my idea was to tell a story on video with scrolling text. I designed a font especially for this. The letter shapes were vaguely architectural, quasi-modernist. The font design program I used (fontographer 4.1) outputted the characters as a Key Map. This meant that I saw the letter shapes in a cartographic way. They suddenly existed in a geographical place. It was a cartography of the self.

I got excited about this pictorialization of language. It took me to the pictorialized word, illumination. I saw words that were unreadable because they were too much ‘pictures’. Words that weren’t words, pictures that weren’t pictures. This naming, place-making, ‘looking to belong’ has something to do with being Jewish, association with non-figurative forms of representation, pre-Christian. It also became an exploration of non-physical being, an incorporeal portrait.

236 1/4 x 118 1/8 inches 600 x 300 cm © Paul Noble. Courtesy the artist and Gagosian.

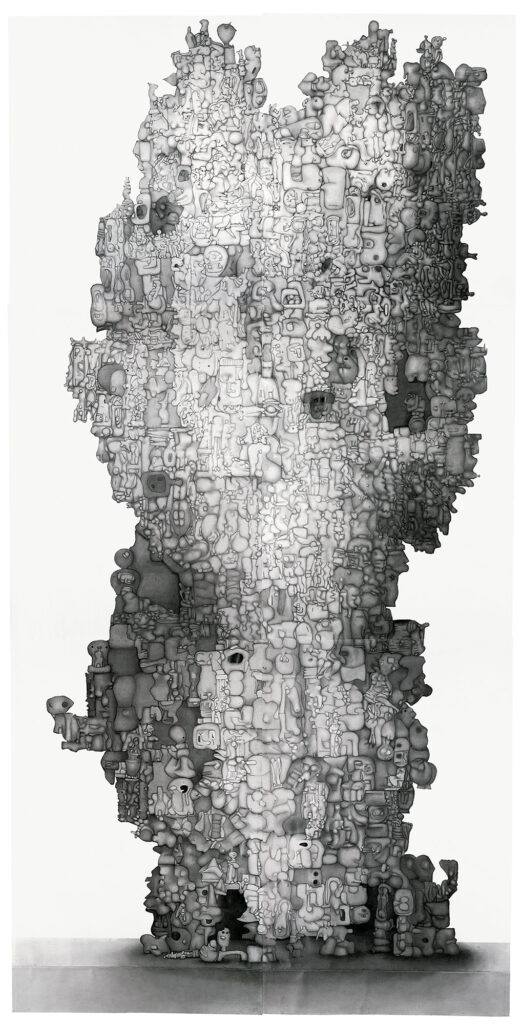

KK: In 2007, you drew a fascinating piece called “Monument monument” based on all of Henry Moore’s sculptures. What was your motivation for this work, was it admiration for Moore’s pieces or a comment on the ubiquity of it?

PN: It is about their ubiquity. His work is really everywhere. I wasn’t a fan of his work and I was critical of his repeated presentations of the nuclear family. His attitudes seemed in tune with the government’s desire to have women back in their place after the war. Aesthetically, I much prefer Moore’s contemporary, Hans Bellmer, who has a much more disorienting response to the brutality of World War II.

The first building I ‘made’ (depicted) in Nobson was called Paul’s Palace(1996). It was a drawing of an architect’s house built on the sand, and beside it was a pile of Henry Moore sculptures that looked like they’d been cleared from their public sites and dumped. It was a very excremental pile. A few years after I went back and looked at this drawing and I thought – I haven’t finished with this yet. I decided to make a giant Henry Moore mountain out of all of his sculptures. I bought his six-volume catalogue raisonee, and re-sized each of his works so they were all equivalent sizes, and then made a towering orgy of intertwined Henry Moore’s. I began, at the foot of the mountain, still a critic of Moore but as I slowly ascended I recognized what a master of form and material and scale he was. It took me a while to get to this point and be rid of my prejudices. “Monument monument” is an excremental monument of his monumental works.

© Paul Noble. Courtesy the artist and Gagosian.

KK: After Nobson, you moved into a different type of work like some of the work shown at La Chaux-de-Fonds and Gagosian in December 2018. I read a review that said it was as if you focussed on one building and dove into it and started drawing the interior in a more focussed way….is that how you would describe that shift?

PN: Not really, no. Nobson was conceived very quickly. I had a ‘eureka’ moment where I found that the fonts were words and images at the same time. I quickly drew a map and made a list of all the buildings that were going to be there, and then I decided to draw the buildings. I thought it would take about 2 months, and then 2 years, and then 18 years later I was still doing it. I was working through the list, still enjoying it, and was energised by it. But when I saw my show at the Museum Boijmans in 2014 I was overwhelmed by the vastness of the space I had invented. It was the first time that I had seen all of the drawings of Nobson together, and I got agoraphobia. I needed to retreat. I made one more Nobson drawing, You Worm, Kneel that was the second half of a diptych that I started in 1997. This is eighteen years later, depicting the same 10.45 a.m. moment.

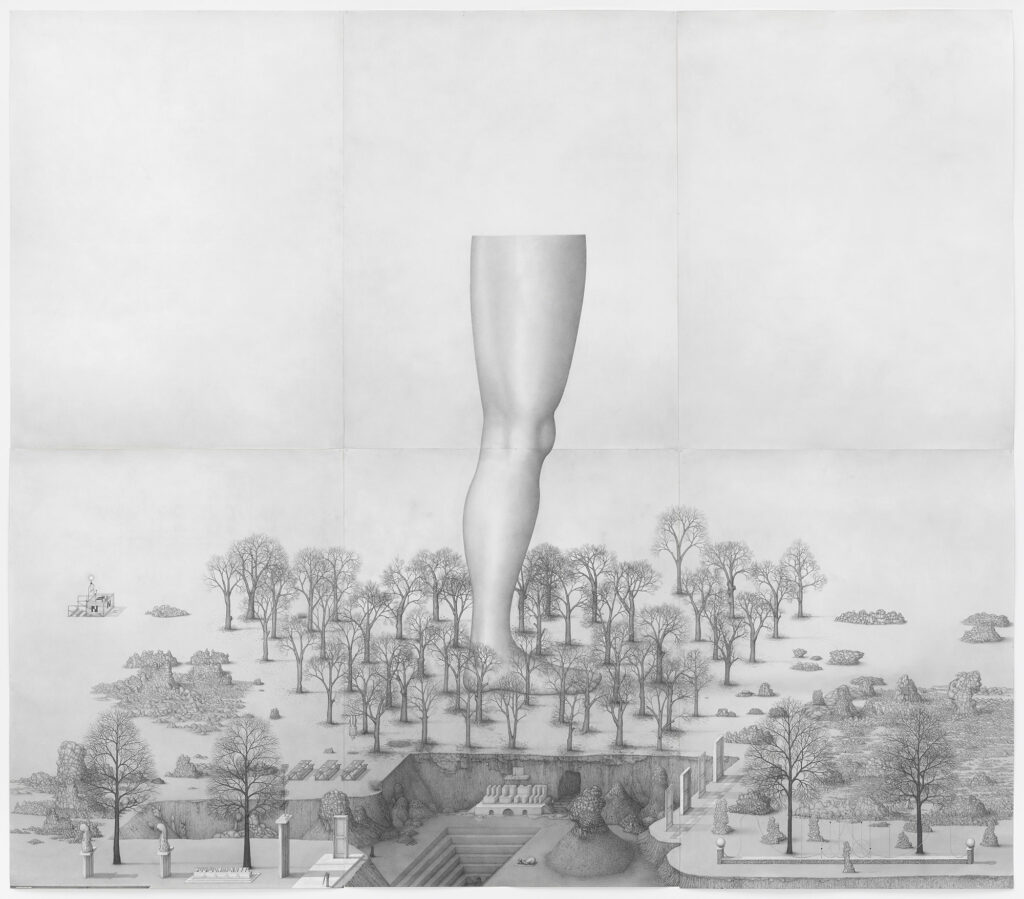

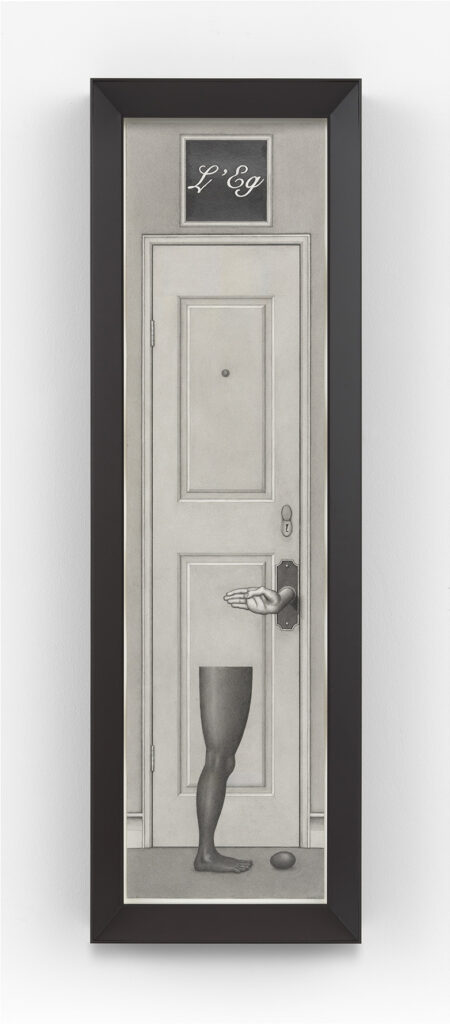

The first part of the diptych is called Obscure Temple of the Starrworm Cult beyond Nobson Newtown. It is 50 x 70 cm. It shows something like a place of sacrifice. You Worm, Kneel is 4 m x 4 1/2 m. These two drawings, among others, depict Nobson’s ‘religious’ moment, a moment within a moment. You Worm shows a captive being, a giant penile leg amidst of vaginal forest. At the bottom of You Worm I drew a little door. On completion of this drawing I passed through this door. I left the outside and came to the inside. The leg, without moving, came inside. The inside began with a door. The leg couldn’t move from the door, either for fear or attraction. Space was flattened. The outside space is a cartographic space, it presents omniscience. The inside is coffinesque.

157 1/2 x 179 1/2 inches 400 x 456 cm

© Paul Noble. Courtesy the artist and Gagosian. Photo: Mike Bruce

KK: You said, “almost all art is against time”. Does this refer to the amount of time an artist has to create?

PN: We are temporary beings that leave droppings, to be scatological, and it is for other people to choose whether it is shit or gold. Future generations will decide whether you add to culture in your way of understanding the current and the future, and whether you have aimed correctly or not, to speak both to now and to the future. We live and die with time, biology demands it. The only escape is art.

KK: You have quite a few clocks in your work. Are you thinking about the limited amount of time we all have when you are creating these pieces?

PN: The clock shows that it is still 10.45. Inside or outside Nobson it is still 10.45. It will always be this time until it is 10.46. The large leg is a representation of a being, captured. The clocks show that time too is captured by the image. I also admit that I felt I had to show the clocks in La Chaux-de-Fonds as it was once the heart of the Swiss watch-making industry.

Artwork © Paul Noble Photo: Prune Simon-Vermot Courtesy Musée des beaux-arts La Chaux-de-Fonds

KK: Do you see yourself as a Surrealist, in the context of your later work?

PN: No. But I do look at a lot of Surrealism, and love it. I am a realist, unfortunately. I would love to be more “surreal”. The norm is surreal. People live in a state of madness (surreality) but culture normalises this madness. People believe and accept irrational and supernatural things because their cultural norms support them. Everyone thinks that it is normal to burn up every last bit of petrol. Burning petrol is associated with achieving freedom, getting from A to B. What is this freedom? Where are we going? Culture says be free. Seek freedom. Why?

Now, I am making culture. My culture attempts to adjust these misguided understandings of how people should live their lives. What you see as my surreality, I see as my reality. What I see of other’s ‘reality’ is their surreality. Like William Blake’s “The Marriage of Heaven and Hell”, he inverted the “morally correct way” because he saw The Church way (cultural norm) as being anti-human. Shit keeps re-appearing in my work. My Shit is beautified, you could say it is Canova-esque, Neo-Classical Shit. Dieified Defecants. It is there to remind us of our proximity to animals. We tend (cultural norms) to think we are superior to animals but we are not.

65 1/2 x 20 1/2 in 166.2 x 52.1 cm

© Paul Noble Photo: Mike Bruce Courtesy Gagosian

KK: I wanted to ask you about the Turner Prize that you were nominated for in 2012. Another artist won that year, and this year, the four artists who were nominated decided to share the prize in an act of solidarity. Did that notion occur to you when you were nominated?

PN: The main winner of the Turner Prize is always the Tate Gallery, because it puts it in the forefront of supporting contemporary art. I don’t really have an opinion about it, to be honest I really didn’t think about it. I was ok about not winning because the main thing about the Turner Prize is that it brings in a much broader public to see your work. Sometimes, mostly, ‘they’, the public, come to have their prejudices confirmed, to see this rubbish that is contemporary art. However, if you want a lot of people to see your work it is a good thing.

48 x 59 13/16 inches 122 x 152 cm

© Paul Noble. Courtesy the artist and Gagosian. Photo: Lucy Dawkins

KK: It has been a year since your shows in Switzerland. What direction has your work gone in the meantime?

PN: There is one drawing from the Chaux-de-Fonds with a striped interior, and I have made some more of those drawings. I am really excited by these. They are partly to do with captivity and the end of boredom. Boredom used to be a difficult but positive thing. As a child, the only thing that really hurt was boredom. Kids now don’t get a chance to be bored. Pain, physical pain, didn’t hurt. Dealing with Boredom was one of the most difficult things to do. Heidegger has written about it. I think it happens when we feel disconnected from time. But then, I’ve noticed, when the conditions are right and people, friends, family groups are gathered by the sea, time stops but without the effect of boredom, boredom is banished, and both humans and animals bask in sand and breeze without a care in the world.

Artwork © Paul Noble Photo: Annik Wetter Courtesy Gagosian

Paul Noble – Edited Biography

Paul Noble was born in 1963 in Northumberland, England. He attended Sunderland Polytechnic, England, from 1982 to 1983 and Humberside College of Higher Education, Lincoln, England, from 1983 to 1986. Noble’s work has been part of numerous group exhibitions, including shows at the Museu de Arte de São Paulo (2001); Museum of Modern Art, New York (2002); Fabric Workshop and Museum, Philadelphia (2003); New Museum, New York (2003); and Migros Museum für Gegenwartskunst, Zurich (2003). Recent solo museum exhibitions include the Migros Museum für Gegenwartskunst, Zurich (2005); Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, Netherlands (2005); and Nobson, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, Netherlands (2014) and Musee des Beaux-arts de La Chaux-de-Fonds (2018). He lives and works in London.

Thank you to Paul Noble and Gagosian Gallery for this interview which was first published in December, 2019.