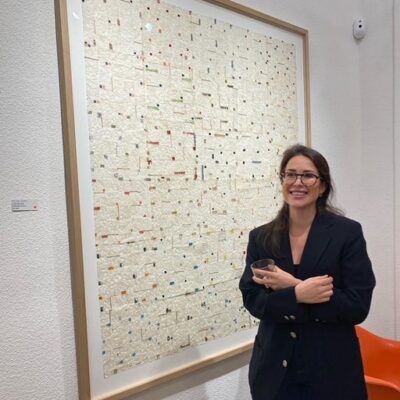

Petrit Halilaj’s Unfinished Histories, Very Volcanic over this Green Feather at the Musée International de la Croix-rouge is part of the museum’s year-long focus on mental health. First created in collaboration with the Tate St Ives in 2021, the piece comprises 53 original wool and felt cut-out pieces dangling theatrically from the ceiling. In this iteration, it has been readapted for the space with several colourful clouds added. The cut-outs display printed scans of scaled-up drawings that Halilaj made when he was thirteen years old in a refugee camp in Albania. Focused on themes of displacement, memory, and identity, this is Petrit Halilaj’s first solo show in Geneva. Kristen Knupp of Art Vista Magazine spoke to the artist who had just arrived from Venice where he is also exhibiting work, as well as participating in a group show at the Bally Foundation in Lugano.

Petrit Halilaj, Histoires inachevées, Musée international de la Croix-Rouge et du Croissant-Rouge, photo Zoé Aubry

Halilaj’s practice goes back to his biography in terms of identity, ideas of home, and memory. Petrit Halilaj is an ethnic Albanian who grew up in Kosovo. When he was twelve years old, the army arrived, took his father, and threw the family out of their house. The family home was subsequently burned down, and Petrit and his family had to flee to the Kukës II Albanian refugee camp. When he arrived in Albania, he was taken care of by Italian psychologist Giacomo “Angelo” Poli who gave him colored pens and paper with which to draw. Halilaj was asked to draw his most beautiful dreams and also his fears. This resulted in the thirty-eight drawings from which the exhibition originates. His work reflects a combination of beautiful birds, flora, and fauna alongside soldiers, burning houses, and tanks. These two universes existed side by side for Halilaj.

His work has always connected to his past, but this is the first time he has re-used his drawings from this period of his life. On one side of the cut-outs is a colorful, light-hearted installation, while on the other are more traumatic elements. In the middle is a boy, the only piece printed on both sides because he exists in both worlds. He had to pass from the universe of fantasy and childhood to the universe of violence and trauma. There are also feathers which are Halilaj’s connection to birds. They are important because they represent the ability to move and migrate. The themes of the exhibition are resilience and the intertwining of storytelling, with visible threads and overlapping fabric on the panels.

Petrit Halilaj, Exhibition view, Tate St Ives, photo by: Guy Martin

KK: What is your connection with Switzerland and how did this show come about, how did it happen?

PH: From a personal point of view, I have an uncle living here, near Basel. When I was younger I was studying in Milan, and for me I could not miss the Venice Biennale, Torino, and Basel. So I stayed with him and I could go see all those things. Then in 2011, I brought a piece of land weighing 60 tonnes to the stand at Art Basel. It was called Kostërc, like the town I was born in, and I asked my family to give me the land for the exhibition. It was 3 x 6 x 3 meters which filled the entire stand. I remember that Art Basel had to install additional columns to support its weight. It was three trucks of dirt, and the idea was very simple, but to make it happen was very difficult. The documents necessary to get this soil into Switzerland, because Kosovo is not in the EU, were very detailed. They had to attest to its origin, analyse radioactivity levels, etc. So even just for soil, the process of moving across borders was impacted by international policies.

Then, for an exhibition in 2012 at Kunst Halle Sankt Gallen, I recreated the jewellery of my mother that she buried underground during the war, and they contained colors of different materials like the brick from our house that burned during the war. Sankt Gallen was a kind of rehearsal for this exhibition in Geneva which is a re-elaboration of a very crucial moment in my life. Related to that period of my life, this is the most important exhibition I have done with the themes of displacement, memory, and identity.

With this exhibition, I have extremely strong memories of the war. For example, one of the fragments is a drawing based on a news story I saw about the first child who was killed in the war. My parents had told us that the war was about adults and that children were safe. I wanted to trust them, but then I saw the news and realized that no one is safe anymore. At the same time, because these drawings are on a larger scale, it removes them from reality. I am surprised by how lightly I can relive these memories.

Petrit Halilaj, Exhibition view at Tate St. Ives, Photo by Matt Greenwood

KK: There are birds and beautiful images mixed with images of traumatic memories from that time in your life. How do these images co-exist?

PH: The only piece that is printed on two sides and the only piece that is touching the floor is the drawing of a boy. It comes from a drawing I prepared to show to Kofi Annan when he visited the refugee camp in 1999. This was the first time I encountered different opinions about who can save whom, who is fragile, and who is strong. As a child, I really thought that if Kofi Annan and the United Nations would understand what was really happening in the war, they would stop it. But my grandfather tried to explain to me that it doesn’t always happen like that. Of course, I didn’t stop making the drawing for Kofi Annan, but I continued to make it and decided to keep it because it was all that I had. I questioned at that point who to trust. The image of the boy represents the idea that even children are not protected during war. Despite this, I still think that the international community can do a lot, especially when we join forces for the right causes.

KK: I read about your work at the Bally Foundation and the beautiful flowers you have created with Álvaro Urbano, and the link to Foucault’s concept of heterotopia, where you have an unreal situation that coexists within the normal human context. Is that something that resonates with you in your work?

PH: I think it does. I think you learn to coexist with both sides, but that does not mean that you learn to accept it, only that borders are artificial. We saw it with Covid, the borders we have constructed are not important, and the sooner we understand that we are interconnected, the better. When we talk about nature and humans, this idea seems so old, most people understand that the interconnection is much more complex. What I like about this exhibition, is that it is about memory and mind space. It is up to you what you want to see and what you want to connect with. You are the animator of the two sides of our existence. When you enter the exhibit you see only one side, but when you turn around you see the other one. This is not about just trees and birds, there is something deeper, so maybe this connects to the idea of heterotopia.

Petrit Halilaj, Exhibition view Tate St. Ives, photo by Matt Greenwood

KK: Tell me about the feathers in the exhibition. Where do they come from and what do they represent?

PH: Actually they come from different places, some from Kosovo, some from a park nearby, some from friends. The feathers are more connected to the idea of two sides, and I like the subtle element of not knowing exactly where everything comes from. I have always loved birds and their migration patterns. When you see how birds migrate and why, and compare that to humans, they are really different paths. I like these parallel lives and ecosystems and how they orient themselves. When I was doing these drawings in this project for Angelo, half of the drawings were about the war, and half were about things that I liked. I think the birds brought me the dignity I needed to be able to tell him about the other things. It was not only about loss, but also about my dreams, and what I loved.

KK: How did studying in Milan influence you? Are there any artists in particular who have been important to what you do?

PH: When I first saw the Biblioteca di Breda in Milano and I saw work by Andrea Mantegna, and all the classical artists up to the modern ones, in person, I was 18 years old. I can compare that experience to some huge natural event that happens, or war. Something that touches you dramatically. Before that, I had only seen things in reproduction and small paintings, and this was the beginning of me realizing the power of art, and the power to tell stories. We have many stories written by others about our history, but it is not a self-written history.

In terms of influences, the Arte Povera movement was very important, and I went to Rivoli, and Torino, and saw work by Alighiero Boetti, Mario Metz, Marisa Metz, etc. Maurizio Cattelan was also an influence, those years were incredible for him, and I remember thinking that his work was so much fun. My approach to materials such as earth, stone, and felt, materials that have a charged human history, is what I want to use. In my work, I want to emphasize the human touch.

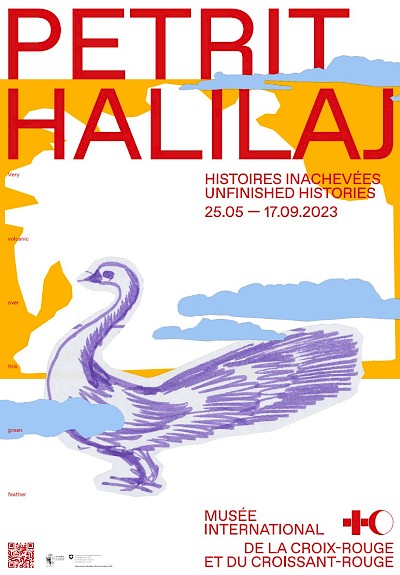

Exhibition Poster, Petrit Halilaj at Musée International de la Croix-Rouge

KK: With the localized, biographical aspect of your work, do you feel that it also resonates on a global level?

PH: My mother is a tailor and I grew up with the idea of putting things together. My work also comes from the idea of theater, where there is a hybrid of languages to allow people to visually experience it. When I presented this exhibit initially at Tate, I was very touched by the resonance it had with visitors from all over the world. Even as a child I was aware of the need to tell this story. There is such a big need to feel that we have the space to tell our own stories. What is interesting for me is how this can be shared in a context such as at the Red Cross Museum. The aims of the Red Cross are globally known, and my work is something that resonates on that level because it relates to the human experience.

The exhibition Unfinished Histories is on view at the Musée International de la Croix-rouge until September 17, 2023.