Just as there seemed to be a light beginning to glimmer at the end of the pandemic tunnel, our world has been blindsided with another daunting and devastating crisis of global geo-political scale. In the weeks leading up to the Russian invasion of Ukraine in late February, as troops amassed at the contested border, the world sat back watching the inevitability of war unfurling right before our very eyes. Waking up to the news that Russia had violated international law to launch an all-out attack on its sovereign neighbor had such a crushing effect on me that I withdrew to my studio to marshal my defenses against feelings of deep despair. Faced with the horrifying realization that yet another senseless war would undoubtedly result in the loss of so many innocent lives (and already has as I write these words), not to mention the widespread repercussions on the livelihoods of countless others beyond the actual battlefield. How can we combat feeling utterly despondent confronted with these latest acts of inhumanity wrought by the human species against itself?

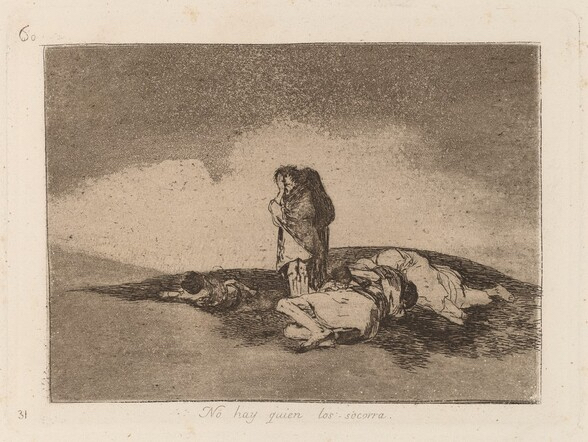

Francisco de Goya, No hay quien los socorra. 1810-1820.

Reflecting on this stark reality, I was immediately drawn to the myriad examples of art that have addressed the atrocities of war throughout the ages and across geography. Romantic-period Spanish painter and printmaker Francisco de Goya’s Los Desastres de la Guerra (The Disasters of War) of course springs right to mind. The series of eighty-two etchings the artist executed from 1810 to 1820 comprises a stunning reminder, in every sense of the word, of the inhumane and all-too-real consequences of military conflict. Responding to the tragic brutality of the Spanish War of Independence as it unfolded, Goya created one of the most gripping, terrifying, haunting visual war narratives of all time. An unflinching condemnation of human folly, this tour-de-force is a monument to the fallen and a testament to resilience as well. Revisiting the heart-wrenching series, I was especially struck by No hay quien los socorra (There is No One to Help Them), which poignantly speaks to the horrendous humanitarian crisis of our current moment. A grieving couple, the woman shielded behind the man who hides his face in despair, stand smack center in a desolate landscape, the barren ground surrounding them strewn with slain bodies. Their indignation and powerlessness to alleviate the suffering and impending death of their fellow humans echo the cries for action reverberating across the planet at this very instant.

Pablo Picasso, Guernica, 1937.

In comes as no surprise that in his wake Goya’s series has inspired many artists who have grappled with the same age-old issues. Over a century later, another Spanish master, Pablo Picasso, bore witness to the ravages of the Spanish Civil War with his monumental oil painting Guernica (1937). Painted following the news of the German bombing of the titular Basque town, the scene vividly depicts the horrific civilian toll of modern aerial warfare in gray tones that evoke both Goya’s black and white suite and the dramatic photographs published in the Parisian press. In the gaping mouths of all the figures—women, men, children, horse, and bull— Picasso visually gives voice to their screams of acute pain and desperation, which resonate with our own pleas against the barbarity unleashed on the Ukrainian people.

Philip Guston, Odessa, 1977.

Toward the end of his life American abstract expressionist painter Philip Guston, whose parents had fled to Canada from the region that is modern day Ukraine during the Russian Revolution, turned to crudely rendered figurative scenes packed with enigmatic yet startling socio-political commentary. In Odessa (1977), a towering pile of shoe soles and their accompanying lower legs seem to float like a cargo ship on the surface of a bright blue sea inscribed with the name of the port city, perhaps a reminiscence of the displacement that his family suffered as well as an evocation of the atrocities of World War II.

Sonia Delaunay, Rythme-couleur 1076, 1939.

My largely figurative sculptural practice seeks to assuage the multifaceted trauma of the human condition by addressing the woes that afflict us and embodying a process of transformation through exploration of our unlimited human potential. My previous columns have delved into these concerns, and I will continue to do so on a monthly basis. But today, I wish to devote the rest of this special edition of my column to the humanitarian crisis in Ukraine by showcasing the life-affirming all-encompassing creativity of an extraordinary artist of Ukrainian heritage, Sonia Delaunay. Born in 1885 near Odessa, she trained in Germany before settling in Paris where she married French artist Robert Delaunay. Her protean boundary-breaking output spanned movements, mediums, and categories, blending art and life in novel and expansive ways through the application of vibrant colors in circular patterns not only to canvas but to artist books, set designs and costumes, fabrics, clothing and accessories, interior design, playing cards, and even an automobile. In Rhythme-couleur 1076 (1939), the colorful curving motifs combine to create a dynamic pulsating image that reverberates beyond the borders of the painting, spiraling infinitely into space in a celebration of life.

For more information about Dr Gindi and to inquire about her sculptures go to dr-gindi.com or @gindisculptor.