The pandemic has brought with it a heightened awareness of many social and human issues – racial and class inequality, questions of ecology and our relationship with other species, for example. But most profoundly, it has brought us face to face with death. Nearly five million people have died worldwide from COVID-19. Death on such an epic scale is at once intensely affecting and unfathomable. We are shocked by death on any scale, even though we know that it is an inevitable outcome for us all.

This taboo around death is deep-seated in many cultures, with notable exceptions, such as Mexico’s annual Dia de los muertos, a colourful danse macabre that defies gloomy European attitudes to mourning. In New Orleans, where Afro-Caribbean traditions dominate, funeral processions are noisy celebrations with live jazz.

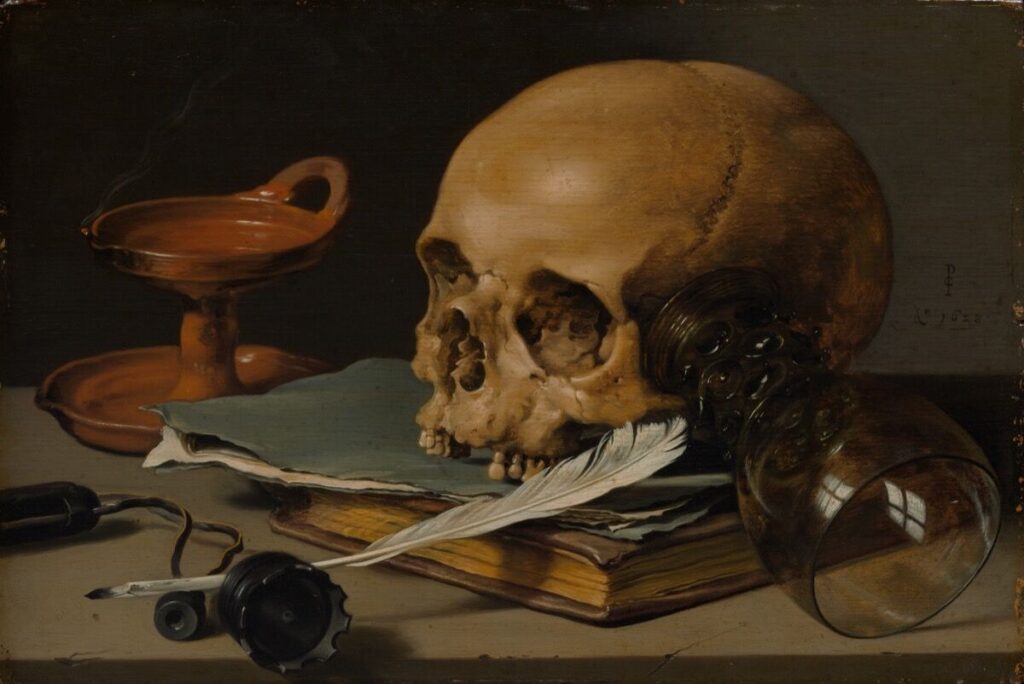

Pieter Claesz, Still Life with a Skull and a Writing Quill, 1628. Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

In European art, the tendency has also been to look at death sideways. Seventeenth-century Dutch still lifes included rotting fruits, fading flowers, dwindling candles and hour glasses as memento mori, or reminders of death. But far from confronting death, these symbols of decay were intended to remind viewers of the short span of their existence on earth, and thus to behave with sufficient piety to earn an everlasting life in heaven.

Hieronymous Bosch, Hell

The works of Hieronymous Bosch (c. 1450–1516) address death more directly. He was also reminding viewers of the wages of sin in his paintings, but his wildly inventive series of hellish punishments – water-boarding with booze, being sneezed on for infinity, or reduced to tagliatelle by giant harp strings – betray a ghoulish delight that goes beyond moralising. Following on from this grotesque influence, Pieter Breugel the Elder’s (c. 1525/30–1569) The Triumph of Death (1562) shows Death as the grimmest of reapers, indiscriminately scything the human population from his emaciated horse. Hans Baldung Grien (1484/5–1545) took an even more profane approach, introducing supernatural themes, sorcery and witchcraft, to explore his preoccupation with mortality.

Ferdinand Hodler, Night, 1890.

The Swiss artist Ferdinand Hodler (1853–1918) also lost his mistress, Valentine Godé-Darel, to illness. He made many touching portraits of her on her deathbed that do not shy away from their subject matter. More menacing is Hodler’s work Night (1890). Here, death is a terrifying black shape, crouching over a young man amongst a group of sleeping figures. As the artist explained: ‘The ghost of death is there not to suggest that many men are surprised by death in the middle of the night … but [that] it is there as a most intense phenomenon of the night.’ So this is a painting about the fear of death.

Dr Gindi, The Last Second, 2021. Bronze, 27 x 40 x 20 cm

Viewers of Hodler’s work were shocked at the time, suggesting that he succeeded in communicating this fear. Shock is also the first reaction of those who see my sculpture The Last Second (2021), in which I portray the final moment on earth of a genderless person as life elapses and leaves the corpse. But although I wanted to evoke the sense of terror at the moment of death, the work is also an affirmation of life, an exhortation to live it in all its intensity and beauty. It shows a dramatic collision of beclouding and becoming.

The Last Second is part of a larger series called Fluidity of Being that deals with the unknown spaces of origin and destiny. Where do we come from and where are we going, now and in our afterlife? Everything is fluid as we oscillate between being and not being. The search to understand what constitutes this state of metamorphosis allows us to glimpse the intricacy of existence.

Dr Gindi, The Last Second, 2021. Bronze, 27 x 40 x 20 cm

My vision and ultimate goal is to encourage the spectator – and humanity at large – to accept the inevitability of death and to see it less as an ending and more as a transition to a different dimension. Perhaps we should view this tragic time of pandemic – when we are all looking differently at life, and beginning to understand that we are an integral part of Nature and not its opposite pole – as a unique opportunity to reappraise our notions about death too.

By considering death a deeper entry into Nature, and not a terminal sentence, we would be inspired to examine our existence, to give purpose to life, and even achieve infinity. Only by acknowledging the fluidity of our being can we enable a previously inaccessible sea of possibilities, and articulate bold visions for the future.

To find out more about Dr Gindi’s work, please go to www.dr-gindi.com or @gindisculptor