William Monk’s Long Museum show from January 13 to March 24, 2024, was his first solo museum exhibition in Asia. It featured nineteen pieces created over four years, from 2019 to 2023, with the title: Psychopomp. This title refers to the guide of the souls; the angels or ferryman who take the dead from this world to the next. In Greek mythology, the ferryman, or Charon carries the dead over the rivers Acheron and Styx to the afterworld to be buried; a physical connection between our world and the next. This is a theme that runs throughout Monk’s work, connecting his imaginary world to ours through work that evokes both ancient and futuristic imagery. William Monk was born in 1977 in England, attended art school at De Ateliers in Amsterdam where he won the Royal Award for Painting in 2005, and now lives and works in Brooklyn. Art Vista’s Kristen Knupp spoke to Monk during his residency at the minimalist masterpiece Neuendorf House in Mallorca, about the Beatles, angels, smoke rings, eclipses, and more.

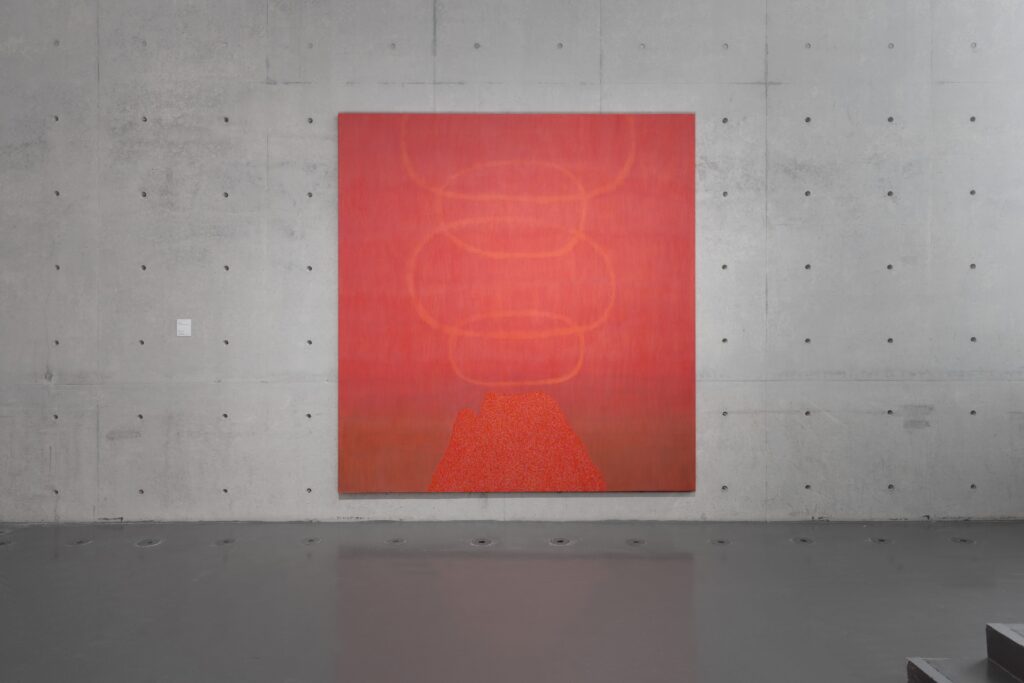

Will Monk: Psychopomp, installation view at Long Museum (West Bund), Shanghai, 13 January – 24 March 2024. Photographs by Xiaoyi Han. Courtesy of Pace Gallery.

Kristen Knupp: I loved the way your colourful paintings interacted and contrasted with the grey concrete walls at the Long Museum. I feel like your work from the Long Museum show was about the in between: in between the living world and the afterlife, in between abstraction and figuration, and the physical spaces between the circular pieces hanging in the rooms and the pieces on the walls. If we begin with the Ferryman works which depict a brightly-coloured futuristic figure in the center of a pastel brushy landscape, the figure seems to connect two worlds together. Where does the image of the Ferryman come from and what does it represent?

William Monk: The Ferryman paintings were born in my mind just before the lockdown. So that would have been in 2019. So, I was thinking about the figure of death in various cultures, and their various guises depending on the culture. In our western one it has a black cape, a scythe and maybe a skeletal face, but in each culture there is a way of manifesting itself into a form. Angels, for example, are another attempt to describe the unimaginable. I am not religious, but if there was going to be a figure of death, it surely wouldn’t be a culturally universal figure that each tribe has to share, instead wouldn’t it be more based on the individual? So what would that look like for me? It would have to look like something familiar and something that you would want to take the hand of and be led across the river. It can’t be a skeletal figure, otherwise you would say no thank you. For example, in The Wizard of Oz, all the things that Dorothy experienced were familiar from her home surroundings. Those who encouraged her in Oz encouraged her back home and similarly what scared her back home equally frightened her in Oz. In the Terry Gilliam movie Time Bandits, you have a young boy who goes on his adventure and you realise at the end that all the things he has seen were all elements in his bedroom. Similarly, in the movie Labyrinth everything is from the young girl’s bedroom. This makes more sense to me. So it would have to be something friendly and born out of my childhood experiences. My favourite movie growing up as a child was The Yellow Submarine. So I took the album cover and just cut it all up, collaged it, and reformed and reconstituted it into my Ferryman.

Will Monk: Psychopomp, installation view at Long Museum (West Bund), Shanghai, 13 January – 24 March 2024. Photographs by Xiaoyi Han. Courtesy of Pace Gallery.

KK: You have talked about the influence of music on your work in the past. Were you a Beatles fan growing up? Do you listen to music as you are making your paintings?

WM: Our day-to-day memory kicks in around five or six years old but before that it is very sporadic. There were various things in my home when I was growing up that I experienced before my memory kicked in. It doesn’t really matter what they were and is almost irrelevant because it could have been anything. The Beatles are amazing and I was lucky that my parents had that stuff. But they could have had awful taste that would have informed me as well. I was lucky that it was those things. So I am not really influenced by the Beatles or The Yellow Submarine, it is my experiences that I am influenced by. Like it or not it all goes into my work, the good stuff and the bad.

As for listening to music in the studio, sometimes I do listen and sometimes I don’t listen. It depends on what I am trying to do in the studio and if I want to be switched on or off. Music, audio or nothing are all beneficial to helping me achieve a certain attitude I want in the studio. Sometimes it is very beneficial to be thinking about the work, sometimes it is beneficial not to be thinking about anything.

KK: Could you talk a bit about your technique and how you create these pieces, what is it about combining abstract and figurative elements that you enjoy?

WM: So often when you read about a painter’s work you read the phrase “the artist’s work lies somewhere between abstraction and figuration”. To me this is a huge redundant cop-out because that is what painting is. That is what every painter does; that is painting. I also don’t see my work as something in the middle of abstraction and figuration. If I was forced to look at it that way, I would see it as wholly abstract and wholly figurative, and the painting operates in both of these spaces. It is not 50% abstract and 50% figurative, it is 100% abstract and 100% figurative and there is a tension between those two positions. Painting is an act and is an object, and as for trying to do it all, you want your paintings to be active. Contrast is where your eye will rest, the mind will wander between these moments. Contrast can be established both physically and metaphysically, abstractly, and figuratively, texturally, in form, and in colour. In music, there is a spectrum of sound that we have described as seven notes and it is infinitely variable. In painting, we have a spectrum of colours and there are equally an infinite number of possibilities.

Will Monk: Psychopomp, installation view at Long Museum (West Bund), Shanghai, 13 January – 24 March 2024. Photographs by Xiaoyi Han. Courtesy of Pace Gallery.

KK: You have a hazy horizontal line in the Smoke Ring Mountain works. I started to think about you as a kind of shaman, communicating between worlds, and if I look at the Smoke Ring Mountain series, it seems to me to be about communication between nature and humans, or humans to humans using ancient means of communication like smoke signals. Do you see yourself as someone who is trying to explain the unexplainable through your paintings?

WM: I think I would be uncomfortable saying what I felt I was doing because it would be like trying to pick up a bubble in the water, it would disappear the moment I tried to get near it. It would be for other people to comment on that if I’m lucky. In terms of creating a painting that series had a very long gestation period. I did a painting in 2005 called Electric Ant. The image was formed when I clasped my hands and I used that form as the land in a landscape. I had a high horizon point with a black sky above it. I painted most of the painting this way and then turned it upside down for some reason, and I instantly liked the painting more this way around. So the clasped hands suddenly became a trail in the sky, and the black sky was now the silhouetted land. All the imagined land stuff became sky stuff, but it didn’t matter because that horizontal line always defined the situation. It doesn’t matter what we put above the line, it will always be read as a sky and land below. I developed this painting into the series you are referring to by doubling up this hand clasp and it becoming smoke rings. Apart from liking the idea of smoke signals, I was quitting smoking around this time so I was possibly seeing cigarettes everywhere I was looking! The other thing is the paintings have no literal scale beyond what the audience believes they are looking at. It is called Smoke Ring Mountain. I liked the idea of giving it a title that suggested a literal place but the painting and name are all made up, and the word mountain will make you think that you are looking at a mountain. But if I called that painting End of a Cigarette then that is what you would see. Scale is always relative to the audience or myself, whoever is standing in front of a painting. I can’t imagine I would ever put a human being in my painting, but if I did I would have to do some mental gymnastics to figure out how that would work. I want the person who is looking at the painting to be the person in the painting.

Will Monk: Psychopomp, installation view at Long Museum (West Bund), Shanghai, 13 January – 24 March 2024. Photographs by Xiaoyi Han. Courtesy of Pace Gallery.

KK: That is interesting, did you say that you want the person looking at the painting to be in the painting? How would that work?

WM: I think that the paintings should work on a macro and micro level. If a painting is good, normally it will look good very close up and far away. That ties back into the figurative and abstractness, the closer you get the more abstract it becomes, and the image comes into focus as you pull out. This can work in reverse also. With social media now, there is another level that the painting has to operate on, it has to look good digitally in ones and zeros, on an iPhone usually. There is an evolution going on where paintings look better online and offer little in-person but a letdown. Or a painter’s work that one might disregard online could actually offer a lot in person. My paintings are often too minimal in the macro, and maximal in the micro to show well digitally. This shouldn’t matter, but people mostly see paintings online first before they would in person and often will see paintings only online. With my paintings, sometimes that which looks repetitive online is far from that in person. If you treat the image as a mantra, then these repetitions actually explode and become something else entirely, but only providing you are in front of the painting and allow it to wash over you. If all you want to do is look online then you can expect a very narrow field of focus. It works with Neuendorf House, where I am staying in Mallorca, because the form is so minimal that the microelements explode. The colour, for example, changes every minute. I’ve been here a month and I still could not tell you what colour the building is. With a photo, you could believe you could describe the colour, but really all you are doing is describing the photo.

Will Monk: Psychopomp, installation view at Long Museum (West Bund), Shanghai, 13 January – 24 March 2024. Photographs by Xiaoyi Han. Courtesy of Pace Gallery.

KK: I think that is what I picked up from the Nova pieces in the Long Museum show, they seemed to be very similar but close up they were all quite different and each painting was fascinating in itself. They looked like large eyes with dilated pupils, or like the sun. Having just experienced the solar eclipse in the US, the power of the sun was suddenly made very clear and how much we rely on it for life. Were these works inspired by the planets, and our physical relationship with them, and the way our views can be eclipsed?

WM: It is difficult to remember what comes first and what informed what. A lot of times I am influenced by the space I am given in which to hang things. A lot of painters will not give much consideration to the space until it’s time to hang. I very much work by starting with the space and imagining how it can be. The sequence of round paintings was born from the New York show at Pace Gallery in 2022 and I re-imagined them in the Long Museum out of necessity. That particular necessity was the mother of this particular hang. But often it is purer than this. In the New York show, I wanted to create a transitional space between the landscapes and the Ferryman paintings. I am limited to a certain degree as I can not build a building from scratch. In New York, I built walls on either side of the entrance, and you could only see one round painting as you entered, and it would literally block your view so you had to walk inside and go around it to see the other paintings. An eclipse as you move around the work, if you like. And because they were all round paintings getting smaller in scale as you went along, our perception is that they are getting further away. This was all intentional.

Will Monk: Psychopomp, installation view at Long Museum (West Bund), Shanghai, 13 January – 24 March 2024. Photographs by Xiaoyi Han. Courtesy of Pace Gallery.

KK: What have you been working on during your residency in Mallorca?

WM: Well, I ordered twelve canvases, and they were meant to arrive a week before I did, but they never turned up. So I went to an art store and bought some gouaches and paper, and I did have some small panels that I brought in my suitcase. So I have been doing some small, modest things that will hopefully inspire new things when I return to New York.

KK: What are your plans for the future?

WM: The show from the Long Museum travels to the Sifang Art Museum in Nanjing, China, and installation starts soon. I am now working on a new exhibition, date and location to be confirmed, that will be a large show with Pace Gallery. There is a lot going on, art fairs and other things. I have had back-to-back shows for the last eight years. I say eight years but I have been saying that for at least two years, so it must be ten years now. I would love to have more time to develop my work. The lockdown was a rare opportunity where the machine took a pause and we had just time. And time is the rarest thing.

William Monk, Psychopomp at Long Museum Instagram Reel: https://www.instagram.com/reel/C4WEoo7xX5E/

Cover image credit: Portrait of William Monk, 2019 © William Monk, courtesy Pace Gallery