The Hockney retrospective exhibition at Centre Georges Pompidou spans his career from 1952 until the present, including his early realistic work, up to his more recent large-scale landscapes. His fascinating double portraits from 1968 to 1971 are also on display and occupy room 5 of the exhibition. Acknowledged as masterpieces, Hockney’s portraits show a mastery of realism, precision and form, with lighting similar to Hopper or Vermeer. The double portraits reveal much about the relationship between the subjects and Hockney’s perception of them. The paintings were prophetic at times, as if Hockney could see beyond the surface of the present. The pieces also showcase Hockney’s intimate knowledge of art history with visual references to other periods and influences.

The arresting double portrait of Fred and Marcia Weisman, “American Collectors”, was painted in 1968. The subjects were avid art collectors who began collecting together in the late 1940s. By the mid-1960s their art collection was well known. After their divorce in 1979, part of the collection was donated by Marcia to the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles. Eventually, Frederick established the Frederick R. Weisman Foundation of Art and opened his collection to the public at his Los Angeles estate. In the portrait by Hockney, one can see the importance of art to the subjects. Art takes the central position, while the people are fitted around it. Their postures mimic that of the totem pole and the Henry Moore sculpture behind them. They are stiff and formal, while her strange grin is echoed in the grimace on the totem pole. The humans embody their art collection; they are statues.

In the double portrait “My Parents” from 1977, the artist delves into the psychology of his subjects. His father looks down at Aaron Scharf’s book on Art and Photography, engrossed, and ignoring his wife and the painter, while his feet seem in motion, just touching the carpet. It was known that Hockney’s father fidgeted during sittings and his impatience with the situation is clearly captured. Hockney’s mother, meanwhile, poses patiently, as requested, hands neatly folded in her lap. She acknowledges with her direct gaze the presence of the artist, her son, and has a benevolent expression. Piero della Francesca’s Baptism of Christ is reflected in the mirror behind them, a technique used in portrait painting that can be traced at least as far back as Van Eyck’s Arnolfini Portrait from circa 1434.

Between them a small cabinet contains a book on Chardin. Jean-Baptiste-Simeon Chardin was known for painting domestic scenes with sensitivity and seriousness; without sentimentality. It is also known that Chardin’s work influenced many artists including Manet, Cezanne, Matisse and, a contemporary of Hockney, Lucien Freud. Chardin was also referred to by Marcel Proust, who in “In Search of Lost Time” (A la Recherche du Temps Perdu) advises a young man to find beauty in the everyday, not just the palatial, and to visit the Louvre and study the paintings of Chardin. Proust’s volumes are depicted on the shelf in the painting as well, perhaps as a reminder of the possibility of beauty in everyday life.

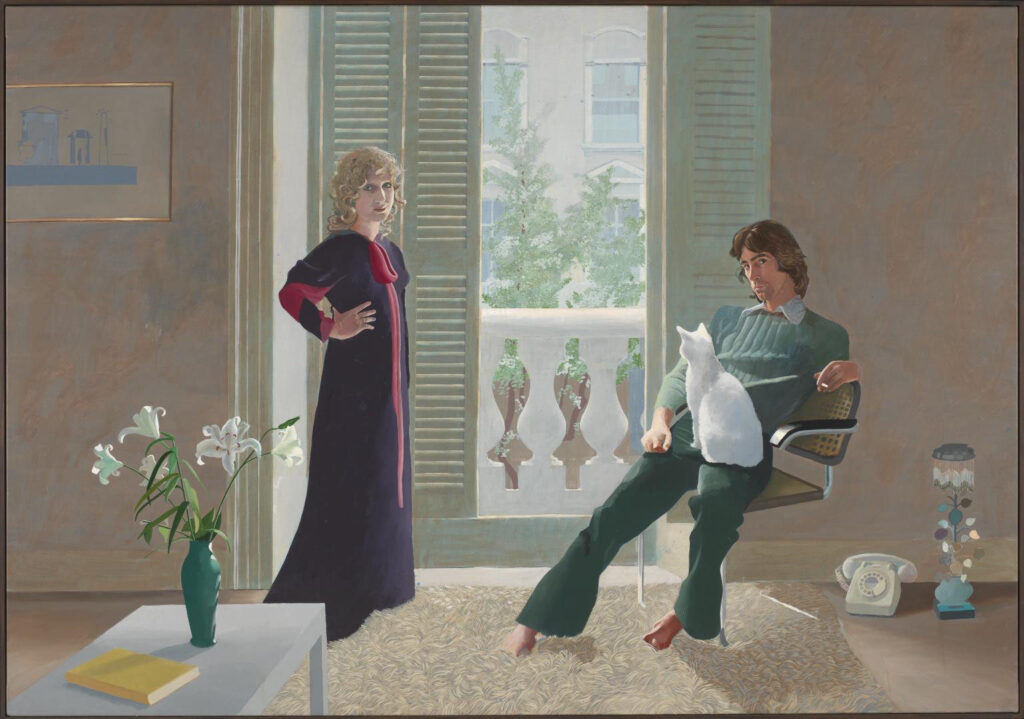

Another interesting double portrait in the exhibition is Mr. and Mrs. Clark and Percy, painted between 1970 and 1971, an acrylic on canvas. It shows the fashion designer Ossie Clark and the textile designer Celia Birtwell, along with their cat, shortly after their wedding and in their Notting Hill apartment. In it, Ossie is seated with the cat on his knee, reflecting the leonine effect of his longish hair and animalistic quality of his facial expression and posture. In the background, perhaps tellingly, is a Hockney sketch for the set of the Stravinsky opera “The Rake’s Progress” which follows the story of Tom Rakewell who leaves his partner to explore the delights of London with a new friend who turns out to be the Devil. Ossie’s gaze is directed at the painter.

Opposite him and on the other side of the window is his wife, in a long, timeless gown, and who is also looking at the painter, not her husband. Next to her are lilies, which are traditionally associated with the Annunciation when the angel Gabriel tells the Virgin Mary that she will become the mother of Jesus, and therefore are a symbol of feminine purity and goodness. The window separates the pair, and as it turns out the symbols in the painting were prophetic, because the marriage did not last.

Other double portraits on view at the Centre Georges Pompidou exhibition include Christopher Isherwood and Don Bachardy, 1968, and Henry Geldzahler and Christopher Scott, 1969. Hockney found painting realistic portraits in acrylic to be a battle and he is quoted as saying about the double portraits, “it was a real struggle. Looking back, I think the difficulties stemmed from the acrylic paint and the naturalism.” He moved on to create photo collages that he called “joiners” and in the 1980’s created a photo collage portrait of his mother. The result is a work with a “cubist” appearance. His portraits featured in one of the largest-ever displays of Hockney’s portraiture work at the National Portrait Gallery in London in October 2006.

The David Hockney Retrospective was at Centre Georges Pompidou until 23 October 2017. This article was originally published in October, 2017.