From June 12 to September 30, the second edition of the Sculpture Garden takes place, a Biennale organized by artgenève this year under the curatorship of Balthazar Lovay, former director of Fri Art Kunsthalle in Fribourg. I spent a Monday morning with Balthazar Lovay, as well as the curator and organizer, Charlotte Diwan, for a guided walk in le parc des Eaux-Vives and le parc La Grange.

The several hectares occupied by the Biennale highlight particularly well the interest shown by artists in their environment, namely the context thought by or for their work. That is to say, a piece developed or moved to a public garden next to other pieces brought together for the same event, becomes more museum-like, since it becomes part of a body of work, a geography, an architecture and an existing history, specific to the place and its function. And if during the 20th century, the context has often been used to emphasize its own effacement, we are dealing here with a much more engaging space.

The nature of the place is special since it represents during these few weeks two superimposable or substitutable functions: that of the public garden and that of the museum. This predisposition then induces different levels of consciousness in the visitor who wanders in a more or less random or organized way, depending on the reasons for their visit. One, an art enthusiast or professional, has come to see the Biennale, the other is sometimes just looking for a place to have a picnic. This one sits in the shadow of a piece and unknowingly attributes a pragmatic and functional status to the work of an artist. It is this functional aspect that some artists have decided to work with, notably Tim Calame (1991) and his metal tables with seats and footrests (Furniture / Documentary # 3, 2020). Robust and hygienic, they easily recall the furniture in institutions (schools, hospitals, prisons). Ida Ekblad (1980) for her part proposes benches (Kraken Möbel, 2020) and encourages the viewer to take a position according to the perceptives she has chosen.

We are at the frontier of the functional with Gina Fishli (1989) and her flags (Geneva, Come Here Please, Auf Wiedersehen, I’m Not Telling You, Swiss Life, Good Dog, Zürich, This Is Going Somewhere, 2020) that she installed on the quays in front of the gardens, although the flag is a more patriotic than a functional element. The production of design students at ECAL uses the principle of the Swiss Bisse (Historic Alpine Irrigation Canals) and recalls the mazot installed in the park for the national exhibition in 1896.

If humans have continued to want to contain and design nature (through the modification of landscapes by agriculture, for example), the park is perhaps the most assumed form, since it is not meant to contain nature but to create it from scratch, or rather its representation. Thus, the city dweller enters an elaborate setting for his own change of scenery. It must be said that parks are reflections of an interesting theatricality to watch. This is notably the case, Balthasar Lovay explains to me, of the work (The Rising and Setting of the Sun, 2020) by Matthew Lutz-Kinoy (1984), a canvas painted in acrylic with an almost marine-grade quality that resists wind and bad weather. The artist wanted to provide a background to the parks that would complement the already existing landscape. The various scenes represented on the canvas create a narrative structure and play with a decorative eroticism both inspired by representations of Rococo woman and the current gay scene. A few days before, a couple settled in front and completed the work of Lutz-Kinoy, re-enacting the scene probably without being aware of the decor which surrounded them.

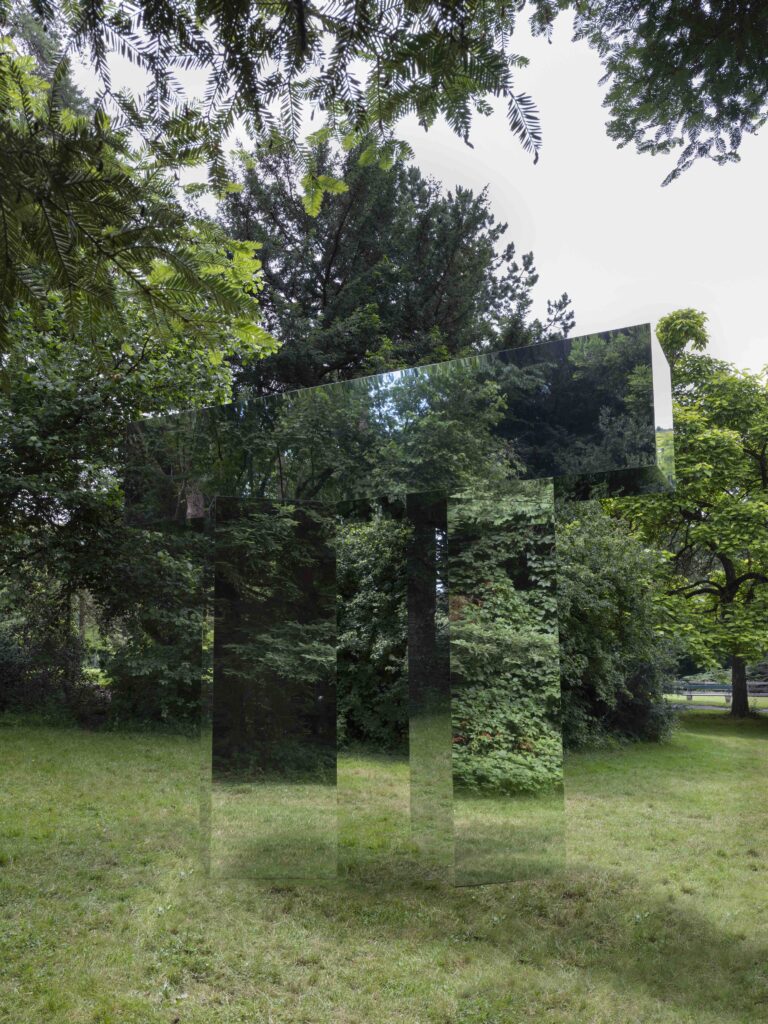

It is quite spectacular to watch these different entities fit together in this open-air museum / theater. And when various elements coexist and respond to each other (art, nature and the public) there is necessarily something to be said in terms of adaptation. The elements that occupy the space simultaneously do not form a very nice and integrated whole at all levels, some protagonists clash with others. Like this piece (Enigma, 2020) by Trix & Robert Haussman (1933 and 1931) constructed entirely of mirrors, a kind of humorous interpretation of the Stonehenge monoliths. Wanting to pass themselves off as the landscape, the work of the designer and the architect brought the crows a new, very territorial adversary: their own reflection. Likewise, the sound piece (Birdcalls, 1972-1981) by Louise Lawler (1947) should not leave the feathered inhabitants of the park unmoved since it is heard listing for 7 minutes the biggest male names of artists of the twentieth century; a reading that she executes by imitating bird songs.

Notions relating to forms of adaptation are also present when we observe the overall selection of pieces. Some that already exist were chosen beforehand, others were specially designed for the Biennale and for the location. In both situations, the works adapt to a context since one already contains a history that it confronts with its new environment, while the other tests the viewer who is observing it for the first time. These visions offer the viewer a multi-speed gaze at what can be a curatorial issue, and the incarnation of a piece through its location.

It is also striking to observe that the field of entertainment intrinsic to the idea of the park coexists here perfectly well with art: an entity considered by some to be an impenetrable and inaccessible cultural juggernaut. The work of Tomo Savić-Geca (1967) illustrates this link particularly well since every evening, the public lighting at the entrance to the park changes its intensity according to the volume of visitors to MAMCO during the day. Without demagoguery and very transparently, the park breaks the psychological barrier of the four opaque walls of the museum.

We look forward to seeing you at the opening of the Biennale on Friday, September 4, from 6.30 p.m. at the Restaurant du Parc des Eaux-Vives!