The Ugo Rondinone takeover or “carte blanche” of the Musée d’art et d’histoire in Geneva marks a turning point for the museum. Established in 1910, the MAH is a repository of disparate collections that have been gathered over its 113 years of existence. It holds 650,000 objects including those from archeology, Egyptology, watches, graphic arts and prints, fine arts, and applied arts. Unfortunately, this has diluted the museum’s focus and following. However, under the direction of Marc Olivier Wahler, who arrived in 2019 from the Palais de Tokyo in Paris, and with the Ugo Rondinone takeover, things are looking up.

This is the third of such takeovers at MAH under the guidance of Wahler who previously worked with Rondinone at the Palais de Tokyo. Born in 1964 in Brunnen, Switzerland, Rondinone is the son of Italian immigrants whose father was a stone mason. It follows, then, that he is perhaps best known for the Human Nature exhibit of Neolithic stone figures in Lincoln Center, New York City, in 2013, as well as Seven Magic Mountains, a grouping of seven stacked stone pillars painted in fluorescent colors located in the desert outside of Las Vegas. He brings this interest in color, contrasts, and making art accessible to the MAH.

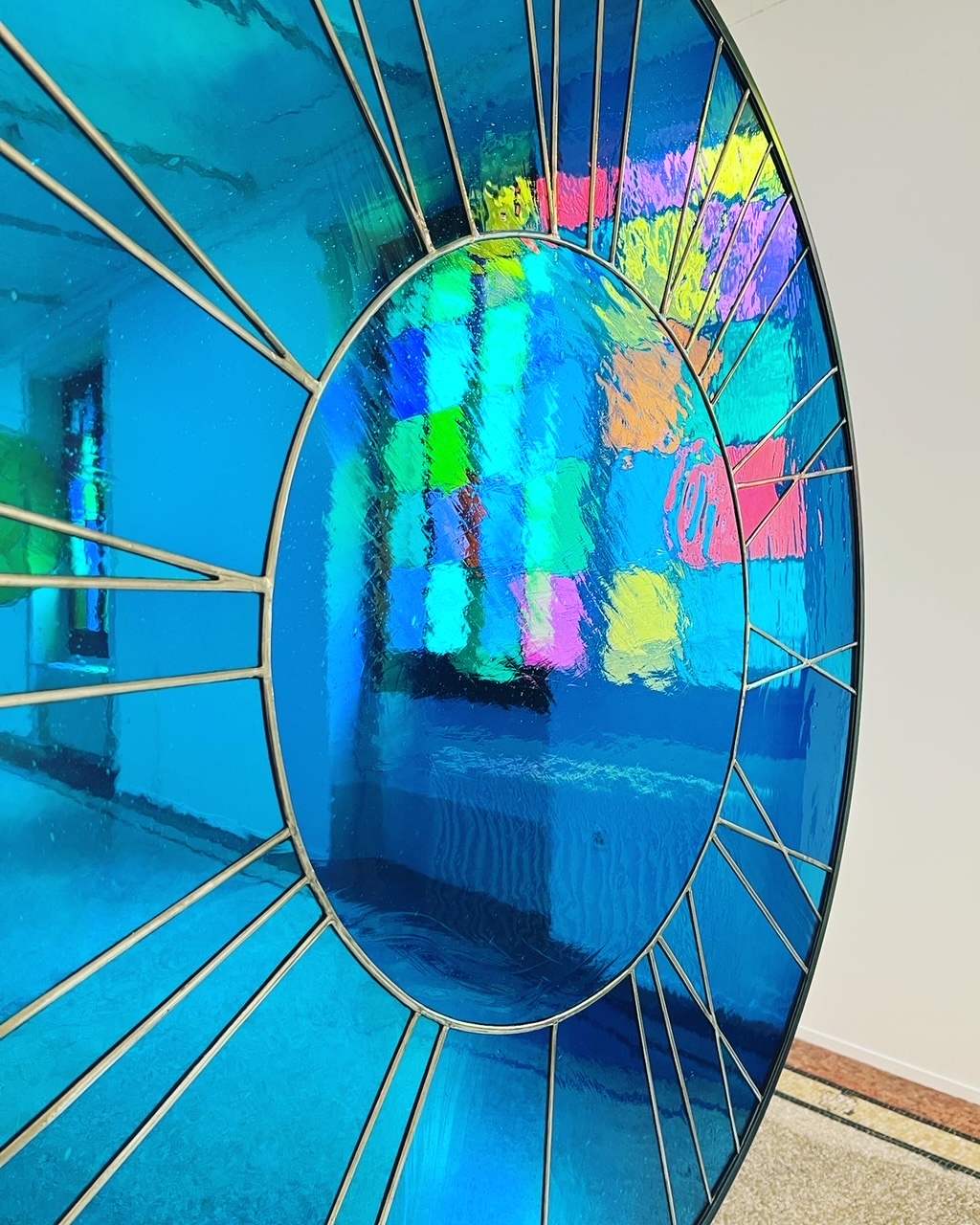

Ugo Rondinone Sun sculpture at MAH entrance hallway. Image courtesy of Musée d’art et d’histoire.

Rondinone has covered the huge museum windows with colored film, a work titled Love Invents Us from 1999. This simple yet clever intervention serves to alter the appearance of all the rooms as well as to unite the objects within. We are keenly aware that the museum is not the same as usual. This is signaled even before entering the museum, with a red digital countdown on the museum’s pediment showing the amount of time remaining before the sun dies. The passage of time is an important theme. Inside, the huge Sun sculpture fills the entrance hallway. The bronze five-meter-high circle made of branches reminds us that the sun is the source of life for all living things. With its scale, it confronts us. At this point one can go either to the left or the right since the exhibit route itself is circular, playing on the floor plan of the museum.

When the sun goes down and the moon comes up exhibition at MAH. Exhibition view with Ferdinand Hodler paintings. Image courtesy of Musée d’art et d’histoire.

In the room Ten Pillars one is faced with Ferdinand Hodler’s over-life-sized warrior paintings standing in the middle of the room backed by plinths. Hodler was a Swiss artist born in 1853 in Bern, who died in 1918 in Geneva. He is revered in Switzerland. 2018 was proclaimed the year of Hodler, on the 100th anniversary of his death. Many Swiss museums, including the Musee d’art et d’histoire, Musee Rath, and Kunstmuseum Bern had year-long exhibitions of his work. Here, the placement of the paintings in the room rather than on the walls forces the viewer to really see the paintings. They are no longer just something to walk past but become sculptures. Themes of masculinity, battle, and war are invoked. In this room, Love Invents Us is red, bathing the paintings in the color of violence, anger, and emotion.

When the sun goes down and the moon comes up exhibition at MAH. Exhibition view. Image courtesy of Musée d’art et d’histoire.

Pathways / Hodler’s Apartment is a complex diorama of layered meanings and interpretations. A fictional apartment has been created based on the character Jean des Esseintes from the 1884 novel A Rebours or Against the Grain. In the novel, Jean des Esseintes withdraws from society to a remote chateau with the aim of surrounding himself with the highest level of beauty possible, including a live tortoise with a gem-inlaid shell. Rondinone, with the help of Geneva-based architect Frederic Jardin, selected objects from the vast museum collection to create this imaginary apartment. Musical instruments, ceramics, carpets, paintings, candelabra, fans, and kimonos are physical evidence of the diversity of the museum’s collection. At the same time, the disparate objects are united under the green glow from the film-covered windows. The theme is repeated in the pink-tinted Vallotton’s Apartment on the other side of the exhibition, and it succeeds in bringing the museum’s collections to the forefront in an innovative, creative interpretation.

When the sun goes down and the moon comes up exhibition at MAH. Exhibition view. Image courtesy of Musée d’art et d’histoire.

Another successful room is Rhythmic Space, Open Sky featuring Rondinone’s eleven glass horses scattered across the tiled floor. The luminous windows are covered in yellow tinted film, filling the room and sculptures with a warm glow. The equine shapes are counterbalanced by seven of Hodler’s lake paintings. Water from eleven seas around the world, including the Flores sea, Sea of Hebrides, Black Sea, etc. fills the lower half of the horses. Horizons in the paintings are echoed by horizon inside each horse, as are the shades of aqua, turquoise and lapis lazuli. Life, water and nature thrive while the next room deals with illness and death. Drawings of Hodler’s mistress, Valentine Godé-Darel line the chapel-like room, reminding one of the end of the cycle of life.

The following three rooms hold three mysterious geometric sculptures created and assembled by Rondinone on site. Tortuous landscape, twisted landscape and tangled landscape made of earth, glue, and wood, fill the parquet-floored rooms, almost scraping the plaster ceilings. Their oversized scale makes for uncomfortable viewing as they squeeze into the space and nearly obscure views of the diminutive white paintings by Rondinone of everyday scenes sparingly placed on dark-paneled walls. A gorgeous gold-threaded tapestry by Swiss artist Philippe Cramer is a highlight.

When the sun goes down and the moon comes up exhibition at MAH. Exhibition view. Image: K. Knupp

Following on is a room filled with clocks of all sizes from the museum’s collection. Grandfather clocks sit alongside petite golden timepieces perched on the roughly-built plinths present throughout the exhibition. Drawings of Adam and Eve, the first humans on earth, dot the walls, while a soundtrack of ticking fills the room. The theme of time continues in a secret room found behind a motion-sensor swinging door. Luminous glass clocks hang from the ceiling alongside colorfully-painted wooden window sculptures and multi-colored windowpanes that fill the room with rainbow-colored light. A second secret room lies behind, and this one is dark and somber. Rondinone’s twin paintings of the night sky stand in the middle, while Savoyard helmets from 1600-1620 line the walls, recalling past battles. A haunted house-style door with bars and huge padlock show there is no escape. The windows are blacked out in a work called Goodnight Geneva. These rooms remind one of the duality of life, both light and dark.

When the sun goes down and the moon comes up exhibition at MAH. Exhibition view. Image: K. Knupp

Next, Rondinone’s Moon sculpture glows in the middle of a gorgeous oval-shaped room with a wood-paneled ceiling, the circular sculpture complementing the room’s sinuous geometry. This marks a shift from Hodler to Felix Vallotton, another giant of Swiss art. Vallotton’s popular woodcut prints from the Intimités series line the walls, and provide a counterbalance to the scale of Rondinone’s sculpture. This leads into a vast room where sculptures of resting dancers lie scattered on the floor, each one made from earth from the different continents of the world. Items from the museum’s permanent collection such as armor cases and Hodler’s warrior painting are covered in black to obscure them, dulling their influence. On the walls, Vallotton’s bucolic landscapes offer a more serene pathway. Finally, in the next room, Vallotton’s paintings of nude females backed by plinths echoes the set-up of Hodler’s warriors on the other side of the museum. The contrast between the soft, sensuous women and the armor-clad men is clear, as are the themes of the multiple dualities of life, the overwhelming presence of nature, and the passage of time. This is a multi-layered, monumental exhibition, and one worth seeing more than once.

For more information please go to the Musée d’art et d’histoire website.