Cuba’s artistic scene, although rich and diverse, is little-known outside of its borders. The exhibition ‘EN PROCESO: Emergences Cubaines’ (In Process: Emerging Cuban Art) aimed to promote and give visibility to a selection of young Cuban artists who rarely exhibit outside of the Island. Held at Espace Témoin in Geneva in September 2020, the show was curated by Laure Testard, a young free-lance curator who divides her time between working at an art advisory firm in Geneva and developing new projects related to emerging contemporary Cuban art. In a time of global lockdown, and limited travel and social interaction, she felt compelled to broaden the horizon of contemporary art and to strengthen cultural exchanges between Cuba and the rest of the world. In this article, she presents the artists from the exhibition which focused on a new wave of young artists who challenge and redefine the notion of ‘creative process’.

Laure Testard:

The pieces chosen for the exhibition, which included installations, videos, photographs, paintings and drawings, were more of an experiment than a limited “artistic result” in which the idea, the concept and the evolution of each work prevailed in the final piece. The public was invited to discover innovative works of art that overcome the stereotypes of traditional Cuban art – which too often defines the perception of Cuban art.

Living and working in Havana, Lester Alvarez (Camagüey, 1984), Gabriel Sánchez Toledo (Sancti Spíritus, 1979), Nelson Jalil (Camagüey,1984), Kevin Ávila (Camagüey,1994), Carla María Bellido (Havana, 1993) and Alberto Regueira (Havana, 1994), find inspiration in their everyday life and cultural heritage to create art which mirrors their contexts while touching on issues that speak to all cultures. Having witnessed their country in a state of transition and in search of openness, these young artists were trained after the Special Period – the deep economic crisis that hit Cuba in the early 1990s – and were determined to create works that mark a break with the multiple references to the past and to the national Cuban iconography. Through their observations and research, these artists became the new chroniclers of a country in constant evolution.

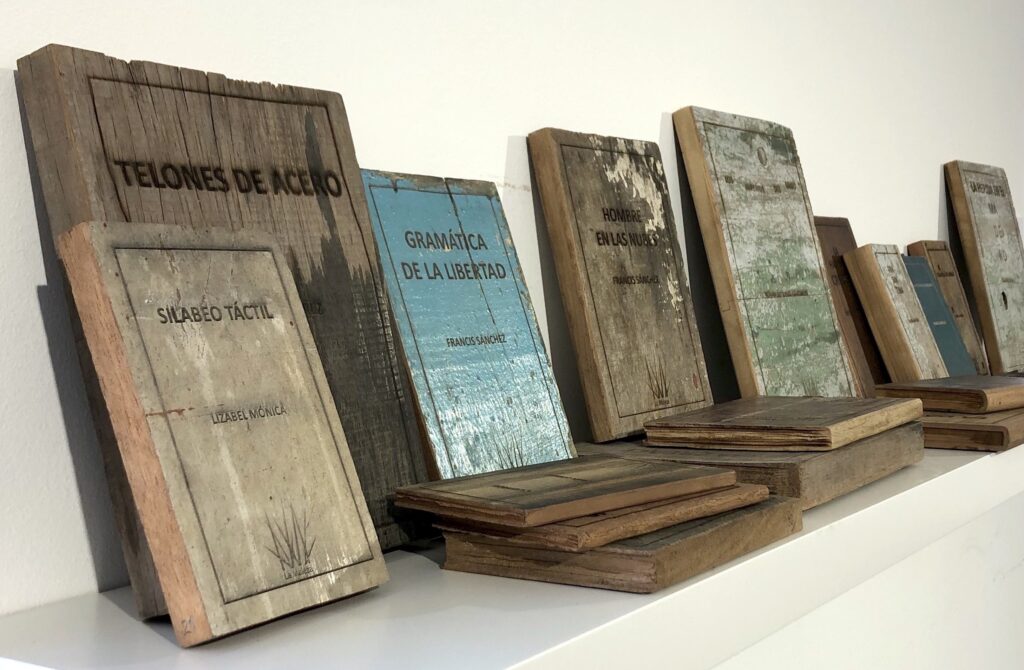

After he graduated from the Faculty of Visual Arts at the Higher Institute of Art (ISA) of Havana, Lester Alvarez developed various projects in collaboration with people and places that are marginalized in his country of origin. The show featured ‘La Maleza’, an installation of books made out of recycled wood. This piece aims to list all the works of Cuban artists that were never published for various reasons (concerns over quality, unusual character or possible censorship). These wooden sculptures are nothing but books without pages, which are thus made unreadable and inevitably lose their primary function. La Maleza eventually aims to give a physical presence to an important part of our culture; the part that lives in the shadows. In the continuity of his artistic approach, Lester Alvarez has created the independent publishing house La Maleza, and has published two books from his original installation. This is a project for which he received numerous grants and residencies.

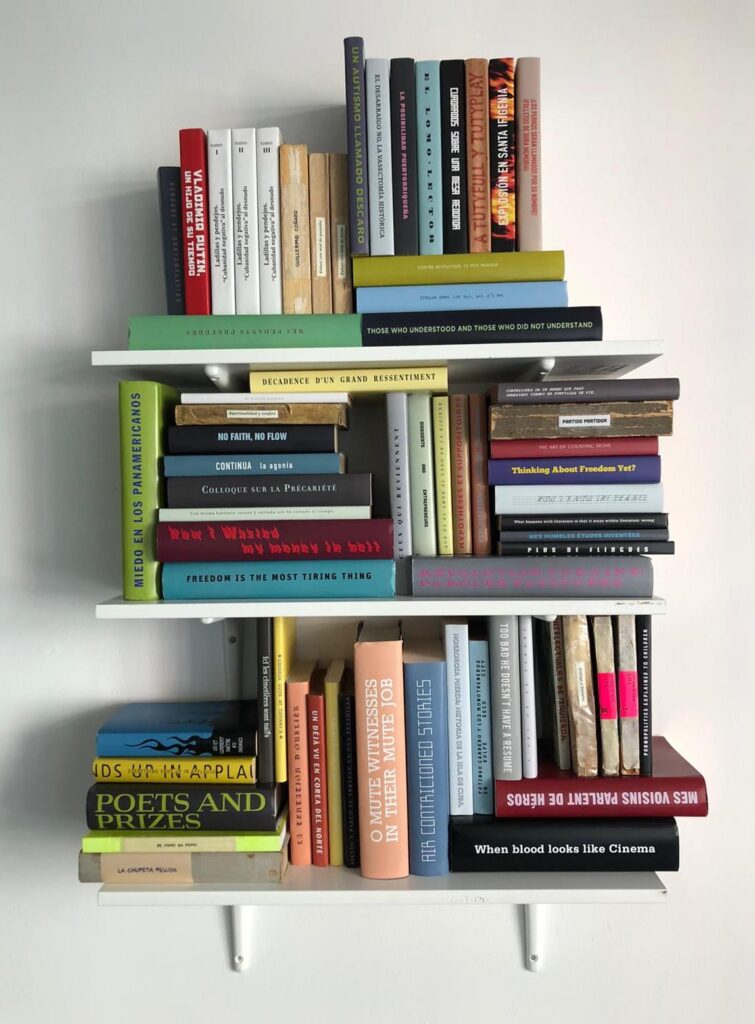

This work is echoed in ‘La Biblioteca para Lomo-Lectores’, a collaborative project created by young artists Kevin Ávila and Lester Alvarez and the writer Roman Gutiérrez Aragoneses. Its title refers to “Lomo-Lector” (Spine reader), a fictional character created by the Cuban writer Hector Zumbado to symbolize the superficiality of our time, with most people reading the spines of books rather than the book itself. More specifically, Biblioteca para Lomo-Lectores is a collective exercise between writers and artists to create fake book covers with fictitious titles. In doing so, they mock the absence of independent artistic reviews in Cuba. Initially exhibited during the last Havana Biennial, Biblioteca para Lomo-Lectores aims to evolve with time, the cultural climate and the exhibition space that hosts it. In this regard, a new version of Biblioteca para Lomo-Lectores-Version de Ginebra was exclusively created for the show in Geneva.

One of the main installations of the show was ‘Descendencia’ by young female artist Carla María Bellido. The work of Carla María Bellido constantly refers to the structures and phenomena that define, consciously or not, what we produce in the field of art. Carla is interested in exploring ‘how much we, as cultural subjects, depend on what we consume, on what precedes us and what constructs us in various aspects’, she says. Descendencia is an installation presenting a set of archives that were collected by a relative of the artist since 1998. This archive brings together articles and photos that document the Cuban art scene from the 1920s to the 1980s. These archives are now in the hands of the artist, who is dedicated to perpetuating this work of research and collection. This installation is thus not an end in itself, but the reflection of a long-term approach which questions the notions of transmission and continuity in the contemporary artistic practice.

The exhibition also featured two large canvases by the young Alberto Regueira. Alberto Regueira’s work is a social and urban exploration that focuses on public order, politics and its actors, as well as contemporary history and its shady parts. Through his formal and conceptual experimentations, the artist establishes a critical examination of his environment, contrasting the intimate, private space with the collective. In ‘Calle Pravda, 24’, details of Soviet architecture seen in buildings in Havana blend into the artist’s grey, drab palette. It is a statement about the way society hides, forgets, and progressively dissolves the traces of history that are nonetheless an integral part of our everyday environment.

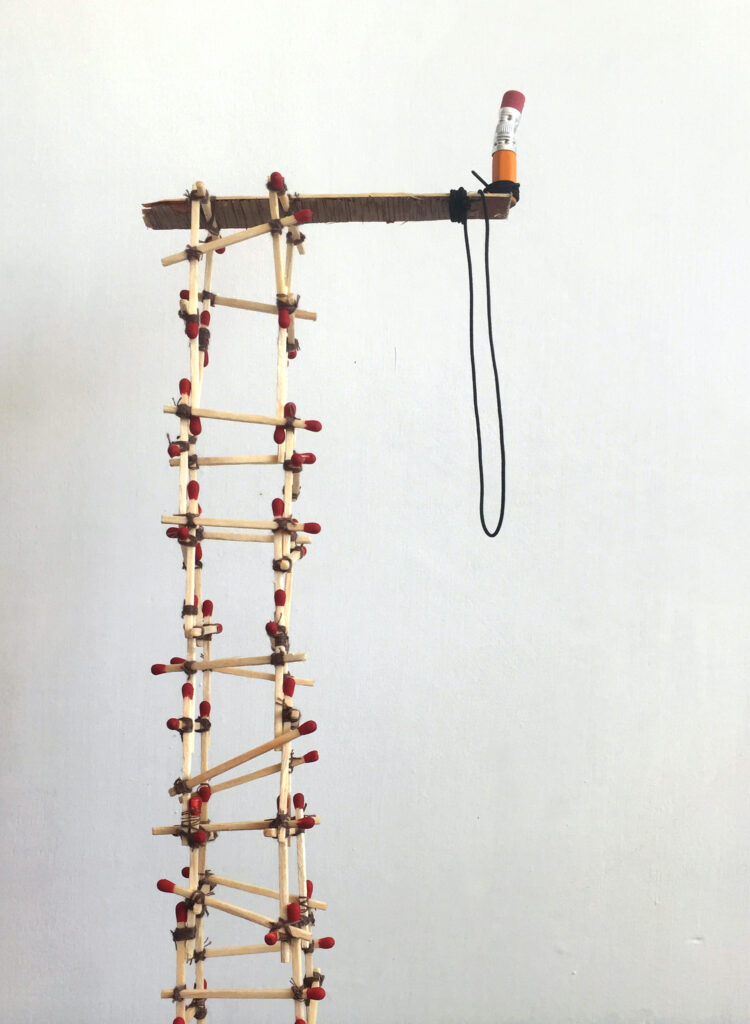

The exhibition also featured the work of Havana-based artist Nelson Jalil. His work is closely linked to the notion of game, leisure and entertainment, and encourages viewers to rediscover childhood. The ‘Escenas Escolares’ (School Scenes) series include objects and small installations that are built from consumables and low-value items. The playful component of the creative process evokes the infantile experience according to which the child indulges in distraction as an escape mechanism during school days. By manipulating and diverting objects from their primary functions, Nelson Jalil puts together a series of ‘ready-made’ objects which explore the links between this creative childish exercise and his actual creative process. These assemblies then become models for small to large-scale paintings.

Also displayed was ‘Desarraigo’ (Uprooting’), a series of six paintings by Gabriel Sánchez Toledo. The artist develops a very controversial genre in contemporary painting: that of the landscape. Between abstraction and figuration, Gabriel’s work is a place of experimentation of material and chromaticism. In his Desarraigo series, undefined spaces become a pretext to exploit the sensoriality of color and the dissolution of materials. Filled with symbolism, these works claim to explore the problems of the human race. The artist undoubtedly leads us to question our relationship to identity, territory and what truly defines our roots.