Following this artistic multimedia immersion in Lausanne, we plunged back into the intimate and very detailed biography written by Rauda Jamis in 1985, Frida Kahlo: Self-portrait of a Woman. Frida Kahlo would have preferred to have been born on July 6, 1910, the year of the Mexican Revolution led by Emiliano Zapata. She was actually born three years earlier, in the famous Casa Azul in Coyoacan, Mexico. She lived there with her parents and two sisters. Her father, Wilhelm Kahlo, a photographer of Hungarian Jewish origins, left Germany in the hope of a better life in Mexico where he married the very pious Matilde Calderon who was a Hispanic-Indian mix.

Of her three first names, Magdalena Carmen Frida, she chose the last, meaning “the power of peace” in German. Lively and sometimes cheeky, this “tomboy” grew up under the benevolent gaze of her father, who saw her full potential. The first drama struck her at the age of six. Doctors diagnosed poliomyelitis in her right leg. The result was an atrophied foot, with one leg shorter than the other. It is thanks to sports that the young girl learned how to tame this physical deficiency. What about the bond with her devout mother? It was not close, and therefore, Frida essentially adopted a philosophy of life diametrically opposed to her mother’s.

Frida Kahlo, The Two Fridas, 1939.

Despite her physical disability, Frida Kahlo was a fighter and ambitious. Her wish was to become a doctor. Entering the National Preparatory School (Zocalo) in 1922, she joined the anarchist group of “Cachuchas” made up mainly of men who were the future Mexican intellectual elite. She has wonderful memories of being surrounded by friends who shared the same human values. Furthermore, at that time, the young woman already stood out from the other students by dressing in German style: navy blue pleated skirt, white shirt, and tie. Among the Cachucas there was the handsome Alejandro Gòmez Arias, with whom she began an academic friendship and romantic relationship.

“To feel in my own pain the pain of all those who suffer and to draw my courage from the need to live to fight for them”. Frida Kahlo

On a hot September day in 1925, Frida and Alejandro boarded a crowded bus heading for Coyoacan. On its way, a small train hits the bus in its center, crushing its passengers until its total destruction. The lovers are ejected and Frida finds herself pierced right through by the handrail. This is only the beginning of a torture that will last until her death with its share of suffering: months of hospitalisation, thirty surgeries, and the amputation of her right leg.

Bedridden for months, she questioned what her life would be like after this tragedy. She read Proust and wrote a lot. She was forced to say farewell to medicine, studies, and the ability to give birth. If despair often invaded her, her will to go on was immense. One day, her family turned her sofa into a four-poster bed and hung a mirror from the ceiling. From this implacable face-to-face was born her need to paint, and to paint herself. Her father provided her with all the materials, and the colors were a joy for the artist in the making. She offered her first self-portrait to Alejandro in 1926.

Frida Kahlo, Autoportrait à la robe de velours, 1926.

“I paint self-portraits because I so often feel alone, because I am the person I know best.” Frida Kahlo

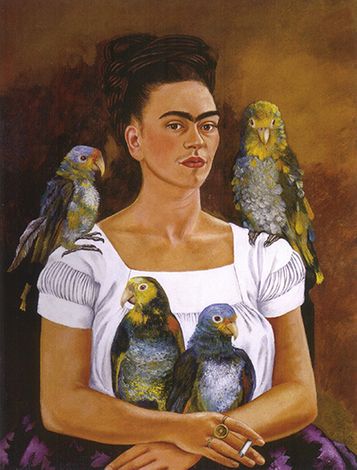

In 1922, she was already interested in Diego Rivera, the very famous Mexican painter, while he was working on a fresco at the National School. This eccentric giant (1886-1957), with bulging eyes, was twenty-one years older than her, but this didn’t matter in their relationship. Art and a political commitment to revolutionary nationalism brought them together irresistibly. Frida loved Diego exclusively and passionately and in return, he became her most fervent admirer and adviser. The elephant and the dove got married on August 21, 1929. Frida immortalized the wedding in 1931, when she painted herself wearing the Tehuana outfit that would make her an icon forever: a large square blouse, a long skirt, and a flowery headdress resting on braids crowning her head. Her efforts at coquetry and the attention she paid to her husband were not an obstacle to Diego’s infidelities, who would even cheat on her with one of her sisters.

“I cannot speak of Diego as my husband because this term, applied to him, is nonsense. He never was and never will be anyone’s husband.” Frida Kahlo

Frida Kahlo, Frida and Diego Rivera, 1931.

Despite being a cad as a husband, Diego constantly supported Frida in her role as an artist. She filled her loneliness by painting assiduously and for hours on small formats for the most part (40cm x 30cm). The only large canvas she created “The Two Fridas” (173 x 173.5cm) was produced in 1939 at the time of her divorce. Her pictorial work is the reflection of her life, a biography in its own right. “Neither Derain, nor I, nor you are capable of painting a head like Frida Kahlo does,” Picasso wrote to Rivera.

Her closeness with the French surrealists, such as André Breton, wrongly connected her to this pictorial movement. According to Kahlo, “They call me surreal, but I’m not. I never painted dreams, I painted my reality.” Of the 143 paintings produced by Frida Kahlo, 55 are self-portraits of her physical and moral suffering. One of them, “Diego y yo” (1949) was sold for $34.9 million at Sotheby’s auction in New York in November 2021. This record places it ahead of Diego Rivera, whose canvas “Les Rivaux (1931) sold for $9.8 million at Christie’s in 2018. She painted her last canvas, “Viva la vida”, in 1954. This painting depicts watermelons in vibrant shades of green and red, which symbolise the link between the living and the dead in Mexico. It is a painting essentially in the form of a will.